Coronavirus: India sees blue skies and clean air as a result of the world’s largest lockdown

The level of particle pollution considered most harmful to human health fell by nearly 60 per cent in New Delhi after a few days

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Inside the world’s largest lockdown, there are no flights, no passenger trains, no taxis and few functioning industries. But one thing is remarkably abundant: cleaner air.

India is engaged in a desperate bid to “flatten the curve” of coronavirus cases before they overwhelm the creaky health system in this nation of more than 1.3 billion people.

In the meantime, the three-week lockdown is flattening something else – India’s notorious air pollution. The speed of the change has surprised even experts, who say it is proof that dramatic improvements in air quality can be achieved, albeit at an enormous human and economic cost.

Days after the lockdown began on 25 March, the level of particle pollution considered most harmful to human health fell by nearly 60 per cent in New Delhi, India’s capital, according to an analysis by experts at the nonprofit Centre for Science and Environment. Similar drops have occurred in other major Indian cities.

In normal times, Delhi is the world’s most polluted megalopolis. For much of the winter, air quality readings remain at levels that in the United States are considered unhealthy or worse. Last November, the city experienced its longest spell of hazardous air since such record keeping began.

These days, Delhiites are stuck in their homes except when picking up essential goods. But above them are blue skies, the moon and the stars, seen without the usual barrier of smog. The sight is so striking that “I feel like complimenting the sky for its beauty,” said Sameer Dhanda, an architect.

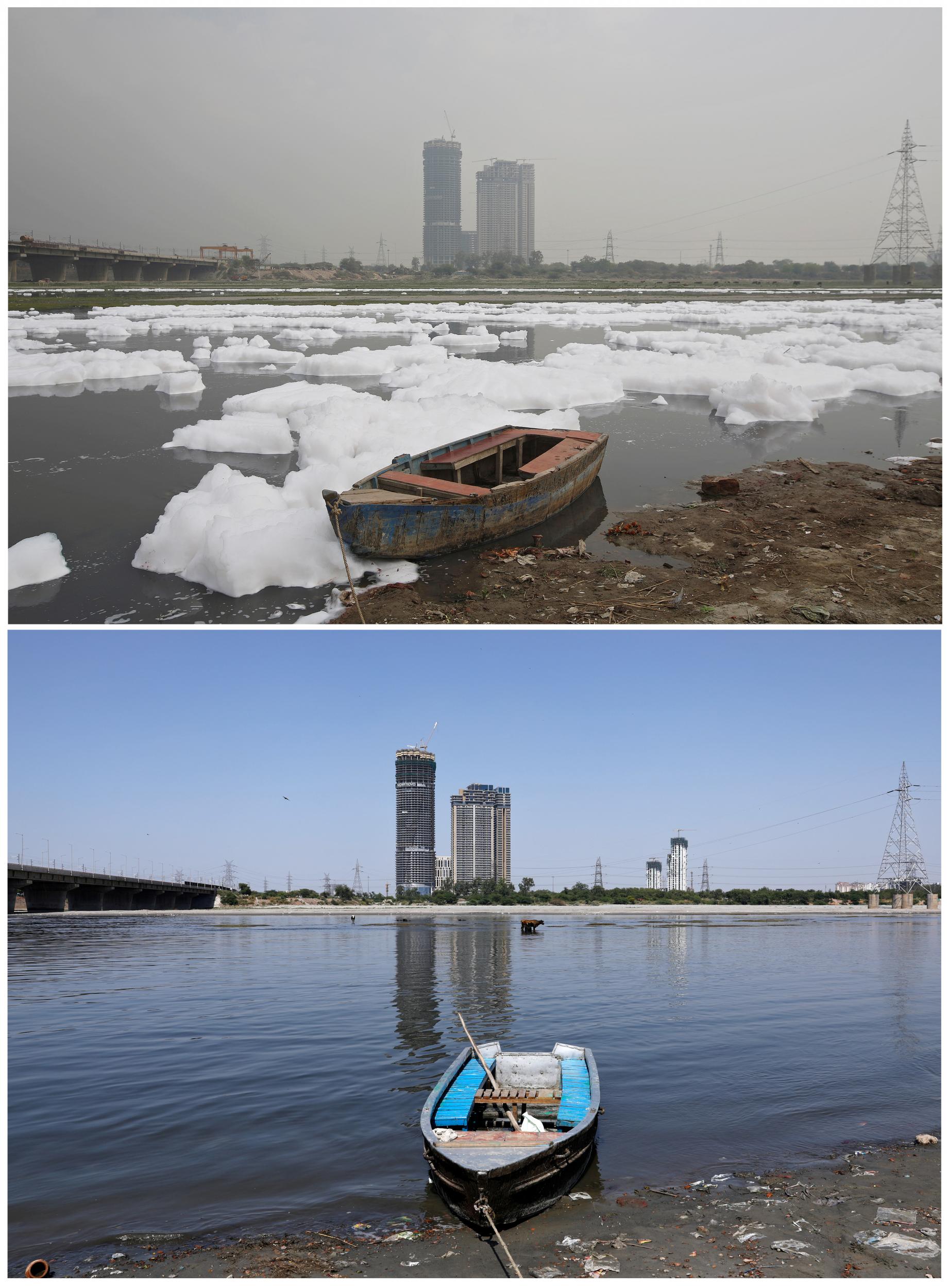

In other parts of India, the Himalayan mountain range is visible from a distance for the first time in years. Waterways choked by industrial pollution, such as Delhi’s Yamuna River – full of grey foam just months ago – are flowing unimpeded.

The current reduction in pollution has come at a steep price. Much of the Indian economy has been idled, forcing vulnerable workers to travel hundreds of miles to their home villages on foot. Millions could be plunged into poverty or hunger if the lockdown continues beyond its initial three-week period.

But experts say that there are still lessons to be gleaned, including a chance to imagine a different future. The decrease in pollution is a “proof of concept” that demonstrates clean air “is doable,” said Ajay Mathur, a former Indian climate negotiator and a member of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s council on climate change. “The linkage between personal behaviour and what I will breathe is far clearer now than it has been in the past.”

The first step for any government is to ensure that “the vast number of Indians have sustainable livelihoods,” Mathur added. Nevertheless, he hopes that policy changes – such as phasing out dirty industrial fuels and accelerating the shift to environmentally friendly vehicles – will get a boost in the post-pandemic world.

Mathur often suffers from a raspy voice and persistent cough that doctors have told him is related to Delhi’s bad air. In the past two weeks, he said, such symptoms have vanished.

One terrible irony of the current crisis is that a pandemic that makes it difficult for some to breathe has, by curbing pollution, eased respiratory troubles for others. Pulmonologists in Delhi say many of their regular patients are breathing easier and reducing their use of inhalers. For them, this period is a kind of boon, said Arvind Kumar, a chest surgeon and trustee of the Lung Care Foundation.

India’s long-running battle with pollution may have rendered it particularly vulnerable to the novel coronavirus. Researchers at Harvard recently found that places with long-term exposure to higher levels of fine particle pollution – known as PM2.5 – were associated with higher rates of death caused by Covid-19. Such particles can lodge deep in the lungs and have been linked to high blood pressure, heart disease, respiratory infections and even cancer. So far, about 200 people in India have died of Covid-19, with more than 6,500 cases of the illness confirmed.

Anumita Roy Chowdhury, an air pollution expert at Delhi’s Centre for Science and Environment, described India’s improved air quality as “a very big unintended experiment unfolding in front of us”. The lockdown demonstrates “the scale at which change is needed,” she said, but also shows people “what it means to breathe clean air”.

Across a huge swath of northern India, the air quality normally varies from poor to apocalyptic, depending on the time of year, with a brief respite during the annual monsoon. The worst period begins when temperatures drop in October, trapping near ground level a mix of industrial emissions, road dust, vehicular exhaust and ash from burnt crop stubble. Pollution begins to ease in February.

Jyoti Pande Lavakare, an author and anti-pollution activist in Delhi, said she doesn’t remember seeing skies of this type of blue at this time of year in at least a decade. In recent days, she began doing her morning exercises outside and found herself lying on her back on her yoga mat, just gazing at the sky.

“After we battle the current pandemic, we need to revisit how we treat the invisible killer of air pollution,” Lavakare said. The World Health Organisation estimates that polluted air kills 7 million people annually.

For now, Delhi residents are treasuring a rare upside of a time marked by fear and worry. Priyanki Choudhury, an account manager, said she has not experienced anything like this – clear blue skies in the day and stars at night – since she was a teenager. Choudhury was not sure whether the lockdown would succeed in stemming the spread of Covid-19. But, for the environment, she said, it is clearly a “time to heal.”

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments