How China changed Macau, ‘the gambling capital of the world’

Twenty years of Chinese rule has transformed Macau’s economy, but as Matthew Keegan finds out, it has come at a price

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Looking out over Macau’s Cotai Strip – the southern Chinese city’s equivalent of the Las Vegas Strip – it’s here, among the glittering lights and neon glow of a parade of extravagant casinos, where the large-scale changes that have transformed the city in the past 20 years are most visible.

It’s hard to believe that until 2007, Macau’s Cotai Strip was just a swamp. Built on reclaimed land, it’s now home to numerous multi-billion dollar casinos that, last year alone, generated more than five times the revenue of Las Vegas.

Friday 20 December 2019 marked the 20th anniversary of Macau being handed back to China, ending 442 years of Portuguese rule.

Since then, this small city – only 13 square miles with a population of around 670,000 – has surpassed Vegas to become the world’s most lucrative gambling city and one of the richest places on earth per capita. Few would have placed their bets on Macau, a once-sleepy backwater, transforming so radically in the past 20 years.

“I never thought that Macau would grow to this level, to become the gaming capital of the world,” says Pamela Chan, a local marketing manager. “Before the handover I hoped that someday there might be some progress in Macau, but I never thought that it would be on this scale.”

Macau’s betting industry was liberalised two years after the handover in 2001, enabling several casino operators from Las Vegas to enter the market. A slew of new gambling dens opened, profits soared, and tourism skyrocketed. Today Macau sees more than 35 million tourists visit annually, with 70 per cent from mainland China. Macau is the only place in China where casino gambling is legal.

Chan says the surge in tourism has made her once laidback and quiet hometown overcrowded. “I do sometimes miss the pre-handover days when Macau was quieter. The traffic was certainly a lot less congested back then. Now we have a lot of casino shuttles taking tourists to and from the different hotels. Some places that used to be visited by local people are now completely dominated by tourists.”

But frustration at the changes in Macau over the past 20 years goes beyond just the increase in tourists. As part of the handover deal, like its neighbour Hong Kong, China promised to grant Macau 50 years of semi-autonomy under a “one country, two systems” policy, set to expire in 2049, in which it would retain its capitalist economic system and people’s rights and freedoms, such as freedom of speech, assembly and religion. But some feel Macau may have already gambled away the bulk of its freedoms; a price it’s paid for an over-reliance on China economically.

“People are afraid to voice their opinions. Freedom of expression is now confined to coffee shops and private spaces,” says Jorge Mensezes, a local lawyer. “There is no democratic progress whatsoever: the rulers are not chosen by Macau people, but ultimately by unelected Beijing officials.”

Mensezes adds that freedom of assembly has been crucially limited in political matters: protests are often just forbidden. There is free press in English and Portuguese language media, but Chinese press is nearly all pro-Beijing.

“Academics seem only free to speak in support of the government. The Bar Association is behaving like a pro-government agency,” says Mensezes. “Businesspeople have no civic participation at all, they bend servilely to the authorities. Non-residents are barred entry in Macau as consequence of their political stances and views.”

Unlike in neighbouring Hong Kong, where protests are frequent, it seems residents of Macau are less inclined to speak out about their declining civil liberties.

“Macau is less than 10 per cent of Hong Kong’s population and because gambling tourism is the city’s main economic driver, it is economically dependent on China to a much greater degree,” says Menezes. “If China tightens the borders, Macau collapses.”

With livelihoods at stake, Macau residents, on the whole, prefer to keep quiet, accepting that economic growth since the handover has come at the cost of decreased freedoms. “Macau people may be nostalgic for some bits of the old Macau,” says Jason Chao, a democracy and human rights activist born in the city. “But the vast majority of the population have benefited from rapid economic growth, and so many are very satisfied with the status quo.”

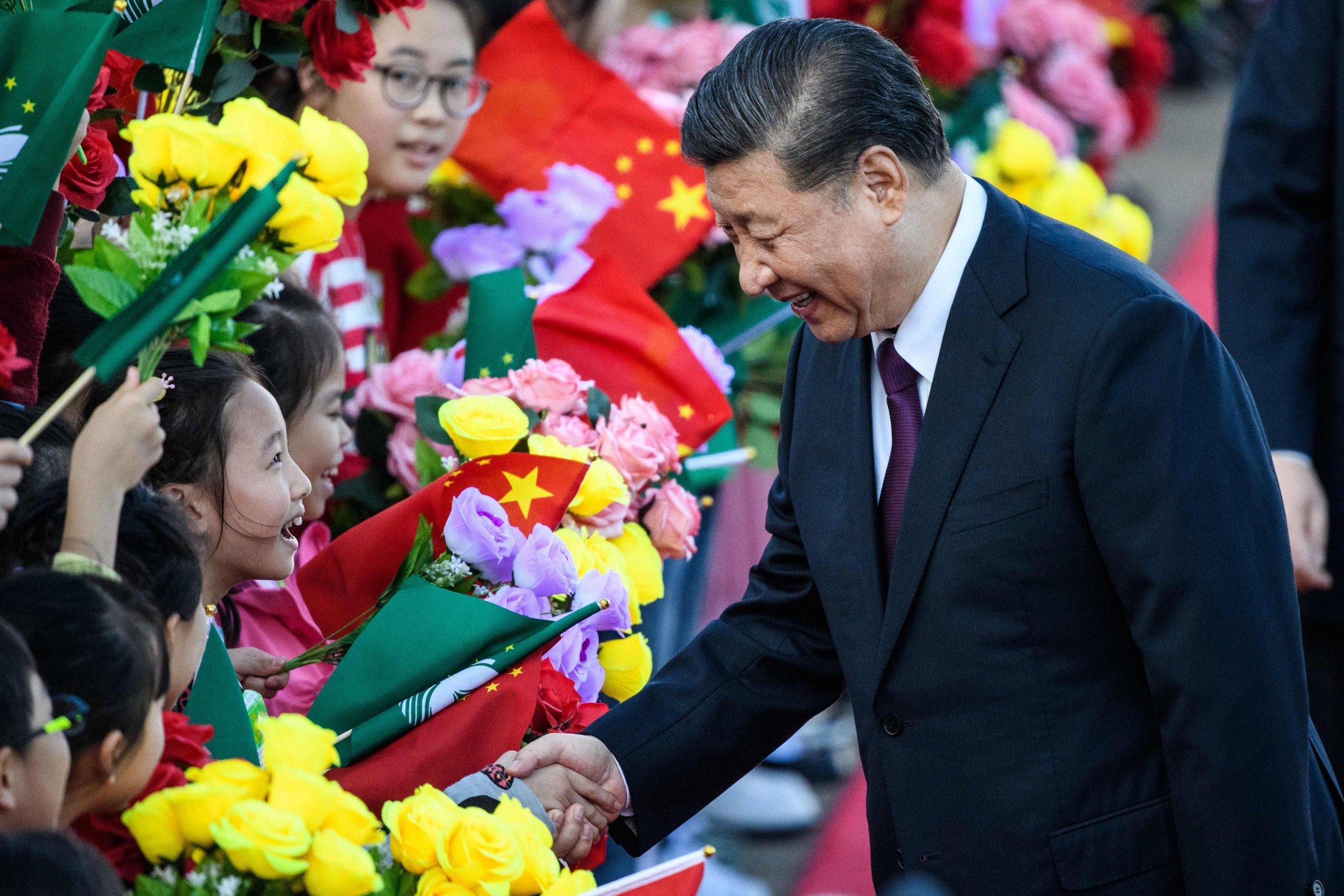

This satisfaction and unwillingness to rock the boat has been rewarded by Chinese officials. Earlier this year, China’s president, Xi Jinping, praised Macau for successfully implementing the “one country, two systems” principle, saying the city has proved that it is “feasible and workable”.

Others disagree.

“China talks of Macau as ‘the good student’, which is a sign of the erosion of its autonomy,” says Menezes. But despite concerns about the erosion of the liberties and fundamental rights promised to its population, some of Macau’s residents remain optimistic about the future, one undoubtedly shaped by further integration with mainland China.

“Unlike Hong Kong, Macau has quite a good relationship with China. So if Macau continues to do things properly, I think the PRC (People’s Republic of China) will take good care of Macau and I think the city will become even more thriving and developed,” says Pamela Chan.

President Xi on Friday officially swore in Macau’s new chief executive, Ho Iat Seng, the Beijing-backed sole candidate of the city’s leadership election.

Back in August, Ho was voted in by a 400-strong committee comprised mostly of pro-Beijing elites. He received 392 out of 400 votes cast.

Most Macau residents realise the election of the chief executive is an elite game that they do not have a say in,” says Leong Meng U, assistant professor of government and public administration at the University of Macau. “So I don’t think people have any specific hopes or expectations regarding the new chief executive.”

But for a city that has experienced mixed fortunes since the handover, there is a still a sense that the 20th anniversary is worth celebrating. “With all its faults in rights and liberties, it celebrates the end of foreign rule and 20 years of stability and economic success,” says Menezes. “And I believe most Macau citizens cherish that more than anything else.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments