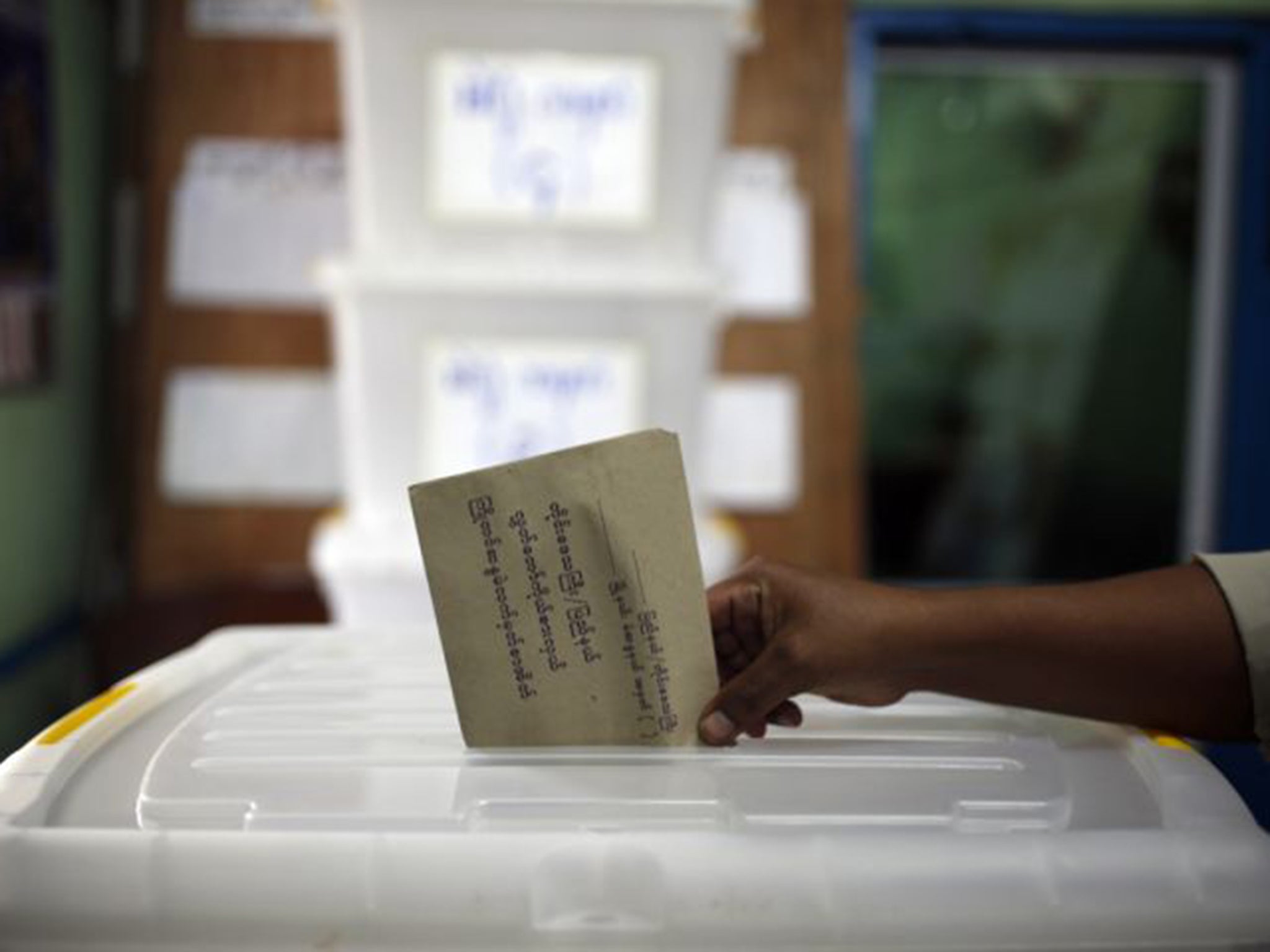

Burma: All eyes on Aung San Suu Kyi as country gears up for free election

Supporters openly show their colours in first poll without censorship for 50 years - but victory is not guaranteed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With one week to go before polling in Burma’s first free election in more than 50 years, Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy are making the running.

Criss-crossing the country just as she did after her debut in 1988, drawing large, enthusiastic crowds, she is also – in the absence of the draconian censorship that persisted until three years ago – getting the lion’s share of media attention. This is the election’s biggest novelty. Her beaming image is everywhere. NLD head office in Rangoon is doing a brisk trade in calendars, key rings, books and memorabilia of every sort. And the party flag of a dancing peacock on a red background flaps boldly on thousands of taxis and rickshaws. For the first time since 1989, her millions of admirers have no need to hide.

“I love the Lady [Suu Kyi] so much,” said San Moe Aye, holding her four-month-old daughter, named Suu, and wearing an NLD bandanna round her head. “If the NLD wins, the poor will be freed from poverty.” A retired bank employee sitting nearby said: “I’ve supported the party since 1988. All Burmese people have been suffering for many years, in many different ways. I believe the NLD is the one organisation that can totally change our country.”

But Ms Suu Kyi is not having it all her own way. In fact, the race is wide open. With one-quarter of seats reserved for serving members of the military, the NLD needs to secure 67 per cent of seats for a majority. Few doubt that the party will do well, but no one knows if it can do that well. The ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), set up by the military regime before it went into voluntary liquidation, won the 2010 election by an apparent engineered landslide, aided by the fact that the NLD, with Ms Suu Kyi still in detention, did not take part.

This time around it is unlikely that the party will be wiped off the map: its grip on rural districts and some border areas may not be strictly democratic but it is powerful. At least some of their seats are likely to survive.

Then there are the ethnic parties, representing the approximate one‑third of Burmese who belong to other ethnic groups than the majority Burmans. If the NLD had forged working alliances with the ethnic parties, a broad pro-federal coalition might now be in prospect. But this the party has failed to do. Many ethnic groups regard the NLD’s overwhelming Burman representation with deep misgivings. So, in the absence of any meaningful opinion polls, Burma is flying blind into the most important election of its 68 years of independent existence.

And in the thick of all the other uncertainties, the biggest uncertainty of all is a former general called Shwe Mann, speaker of the Lower House and, as such, the third most powerful figure in the nation. He has become Ms Suu Kyi’s closest and most intriguing ally outside her party.

Tall and slim, far younger in appearance than his 66 years, calm as a Buddha and with a mild, almost feline speaking manner, Shwe Mann was strongly tipped to become President in 2010. Instead he was pipped to the top job by his charisma-free junior, ex-general Thein Sein. Leader of the USDP, and appointed Speaker as consolation prize for not being President, he has done more to advance the cause of the democratic transition than the rest of the ex-military politicians put together, turning Parliament from the rubber stamp body it was expected to be into a genuine force in the land. In the process he has also wooed and won Suu Kyi. He helped her become chair of an important new parliamentary committee on the rule of law. And he braved the fury of the military establishment by tabling a debate on the taboo of taboos, revision of the constitution, which triple-locks the military as the de facto power in the land.

The motion on the constitution went nowhere, killed by the military bloc vote, and Shwe Mann paid for his temerity with his job, sacked in a late-night purge in August when he was on the brink of nominating a raft of his allies as candidates for next Sunday’s election.

But instead of sulking in his tent, he has come out fighting, campaigning for a parliamentary seat in his home town of Phyu, three hours north-east of Rangoon. On 31 October, he held his final campaign meeting in the town – and offered observers fascinating clues as to how he sees his country’s future.

The decorated ex-general wanted the world to know that he understood how much Burma has changed. “Now we are in a democracy,” he said, “a different form of government that requires total dedication. We have to take care of law and public opinion; we cannot depend on people obeying orders. Our people are living below the poverty line. So we have to change everything.”

He urged the political parties not to fight each other, as they did in the chaotic 10 years of democracy post-independence, but to collaborate, as their aims were the same.

Answering questions, he revealed that he had visited Germany and Denmark and studied their coalition governments. “Germany lost the Second World War but developed fast afterwards due to its democratic federal system,” he said. “I was surprised to learn that there have been coalition governments there for a long time.”

Later at a press conference held in a Buddhist temple’s prayer hall, he denied that he was discussing plans to form a coalition government with other parties post-election. But that was the obvious inference from his words.

Of course, his abiding limitation is his affiliation to the hated military, accused by many Burmese of numerous war crimes over the past 60 years, crimes for which no senior officer has expressed any regret.

“Are you willing to express regret for the army’s actions?” I asked him. He smiled a pained smile.

“I don’t want to say anything now,” he said finally. Then, in English: “You will have to wait and see.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

41Comments