An empty chair, but Nobel jury makes its point

Paul Vallely explains why Beijing should be rattled by today's award ceremony

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

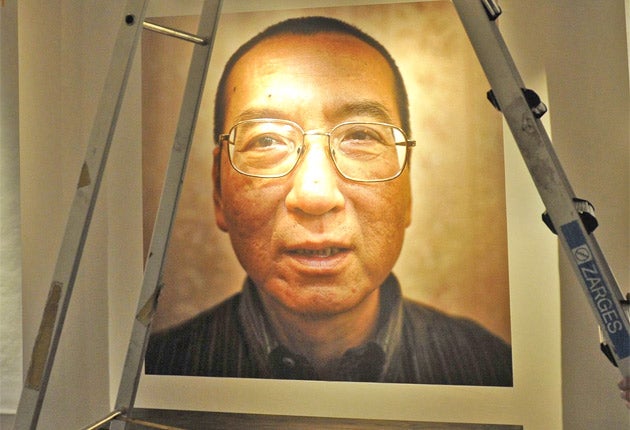

Your support makes all the difference.China's heavy-handed reaction to the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to pro-democracy campaigner Liu Xiaobo may have reaped some short-term rewards. But although 19 nations have now capitulated to pressure from Beijing to boycott tomorrow's ceremony – where the recipient's place will be taken by an empty chair – human rights advocates yesterday predicted that the government's behaviour would ultimately help the Nobel committee to energise China's human rights movement.

So far the picture for activists in China has only become bleaker. Reliable reports from hundreds of people affected by the clampdown Beijing has put in place since news of Mr Liu's award was announced have reached Amnesty International.

"We know of 274 people who have been arrested, placed under house arrest, refused permission to travel or who are unable to go about their daily work, and there may be many more," said Amnesty's China specialist Harriet Garland. But the Nobel announcement has greatly raised morale in the Chinese pro-democracy community. In sharp contrast to the prize committee's widely derided selection of Barack Obama in 2009, the selection has fulfilled the committee's rationale of re-energising beleaguered campaigners and drawing the world's attention to a major human rights issue.

"Awarding the prize to Liu Xiaobo has had an electrifying effect on the human rights community," said Sophie Richardson, a China analyst with the lobby group Human Rights Watch, who is in Oslo for today's ceremony. "It's so long since anyone has so firmly expressed opposition to the Chinese government's hostility to human rights.

"It supports and vindicates not just human rights activists but everyone in China who is trying to make the government more accountable," she added. "It says to all those people in China that their ideas are valid and will be supported by the outside world."

Beijing further undermined its own position yesterday with the launch of a rival peace prize, the Confucius Prize, which appeared to descend into farce when a spokesman for the putative recipient, the former Taiwanese vice-president Lien Chan, claimed he had never heard of the prize and had no intention of collecting it.

Moreover the list of those governments supporting the Chinese boycott – which includes Russia, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Kazakhstan, Tunisia, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Venezuela, the Philippines, Egypt, Sudan, Ukraine, Cuba and Morocco – constitutes an axis of weevils whose record on human rights is not exactly luminescent. "We weren't anticipating a change in the attitude of the Cuban and Vietnamese governments on human rights violations," Ms Richardson added.

So thin is real support for Beijing's blustering outrage that Chinese diplomats have been resorting to blackmailing the staff of Oslo's Chinese restaurants to turn out for anti-Nobel protests today. China's high-octane reaction has underscored the very case that Liu Xiaobo was making in Charter 08, the document calling for gradual political reforms, which he co-authored in 2008, and which got him an 11-year jail sentence for subversion.

"The focus this week has all been on reaction diplomatically, but the real challenge for the Chinese government is domestic," said Tom Porteous, director of the London office of Human Rights Watch. "The Nobel Prize going to Liu Xiaobo has made people in China ask who he is and why he is in prison. When they find out it is just for peaceful campaigning for democracy, that puts pressure on the Chinese government and gives support to those inside it who are pressing for reform."

Harriet Garland at Amnesty agrees. "The authorities fear him as an influential figure within China. Now they have cast themselves in the role of villains instead of taking it gracefully and using it as an opportunity to release him."

What Liu Xiaobo makes of it all we can only guess. But when the veteran of the 1989 pro-reform protest in Tiananmen Square was, for the fourth time, sentenced to prison in 2008, he said that he had been absolutely confident that he would be jailed – and added: "I don't fear it. I see it as a necessary step in a journey."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments