Woman says she’d ‘rather be dead’ after she was intubated against her wishes

Marie Cooper woke up strapped down and with tubes coming out of her body

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An elderly West Virginia woman said she would “rather be dead” after being intubated against her wishes and developing devestating complications.

In February, doctors found cancerous cells in 81-year-old Marie Cooper’s stomach. Soon after, she visited the hospital for a routine stomach scope to determine the serevity of the cancer but after the procedure, Cooper’s daughter, Sherry Uphold, found her mother in a panic and gesturing to say she couldn’t breathe.

Cooper became distressed and “uncooperative,” according to her medical record, per a report fromThe New York Times, prompting doctors to restrain her and insert a breathing tube down her throat despite her having “do not resuscitate” and “do not intubate” orders on file for decades.

Upon awakening, Cooper found herself strapped down and with tubes and IV lines protruding from her body.

“They had me tied down,” Cooper told the outlet. “I was scared to death.”

Uphold described her mother as a Christian who believes “when its her time to go, that’s God’s choosing, not hers,” and she motioned that she wanted the tubes removed.

“If you take that out, you’re committing suicide,” Uphold told her mother. “And if I take it out, I’m murdering you. I won’t do that,” she said as Cooper nodded and squeezed her daughter’s hand to show she understood. When confronted, doctors couldn’t explain why her mother had been treated against her will.

The breathing tube remained in place, but Cooper developed pneumonia and went into septic shock. Days later, she was strong enough for doctors to remove the tube and release her home for hospice care, but the seriousness of her sickness and intubation now means she needs constant care and is unable to bathe, dress or cook for herself.

She also wakes up in terror most nights, pulling at phantom tubes she can feel “all over” her throat, she told the Times.

Illustrating the severity of her experience, Cooper said: “I’d rather be dead than live like this.”

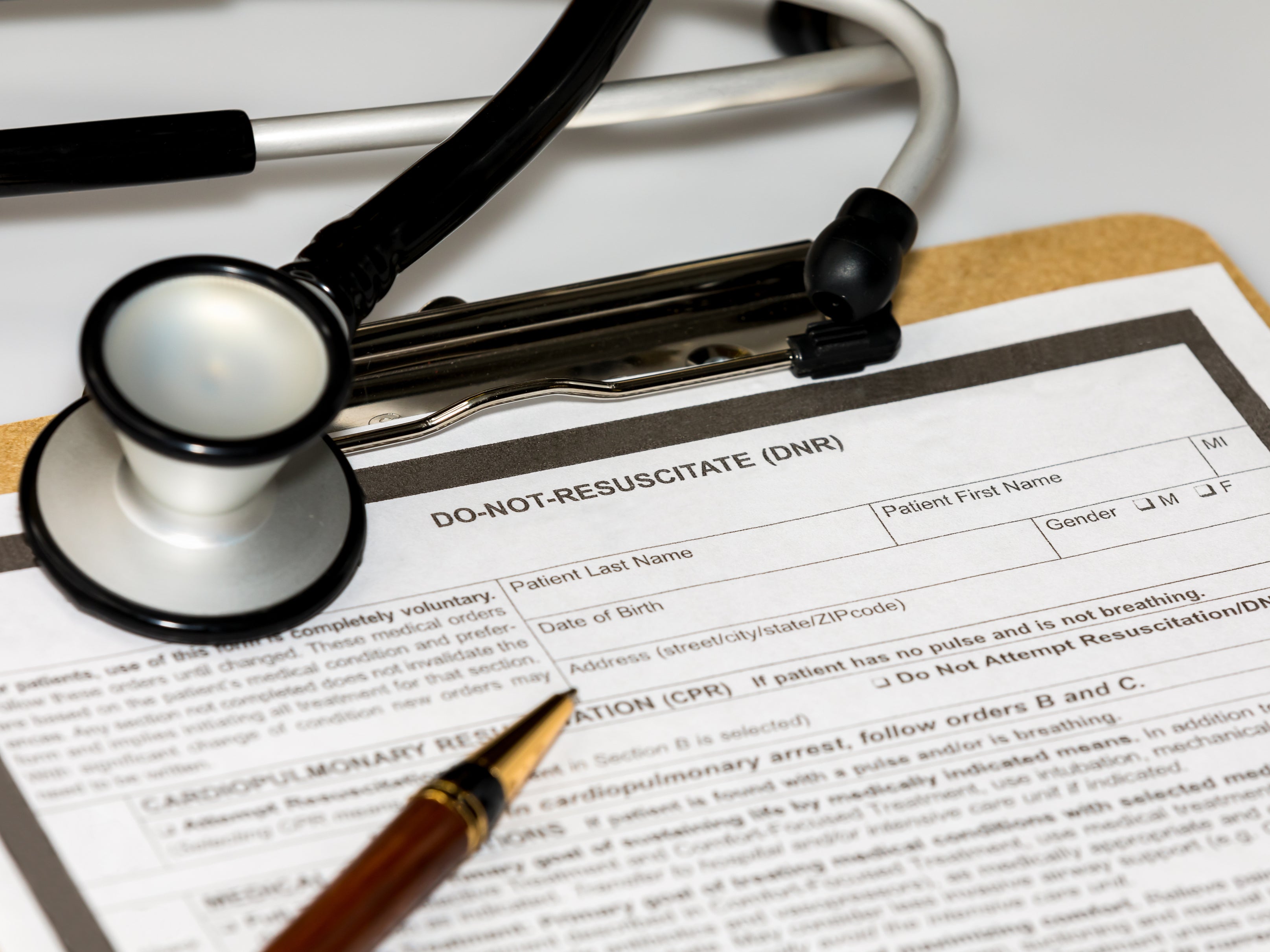

DNRs and DNIs are medical orders written by healthcare providers for people who have decided they do not want resuscitative measures taken if their heart stops beating, or in some states if they stop breathing.

The New York Times reported that between 10 and 20 percent of hospitalized adults in the US have DNRs in place, with those older than 85 up to four times as likely as those under 65.

In fact, citing a 2021 study on survival and quality of life for older cardiac arrest patients following CPR, the outlet said only 12 to 19 percent of older patients who undergo resuscitation procedures after a cardiac arrest survive to discharge.

Medical professionals can misunderstand what patients want because of the changing definition of “resuscitation,” as what was once synonymous with CPR can now include ventilation, intubation and defibrillation.

“Do not resuscitate does not mean do not treat,” said Mathew Pauley, a bioethicist at the Kaiser Permanente hospital system in California, according to the Times.

But limited research reportedly shows doctors can also knowingly override DNRs, rather than misinterpret or not have received the orders.

According to a 1999 survey of 285 medical practitioners, 69 percent of respondents said they would override a DNR in a case of physician error.

Uphold is reportedly seeking legal counsel to prevent another family from enduring what she and her mother have over the past year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments