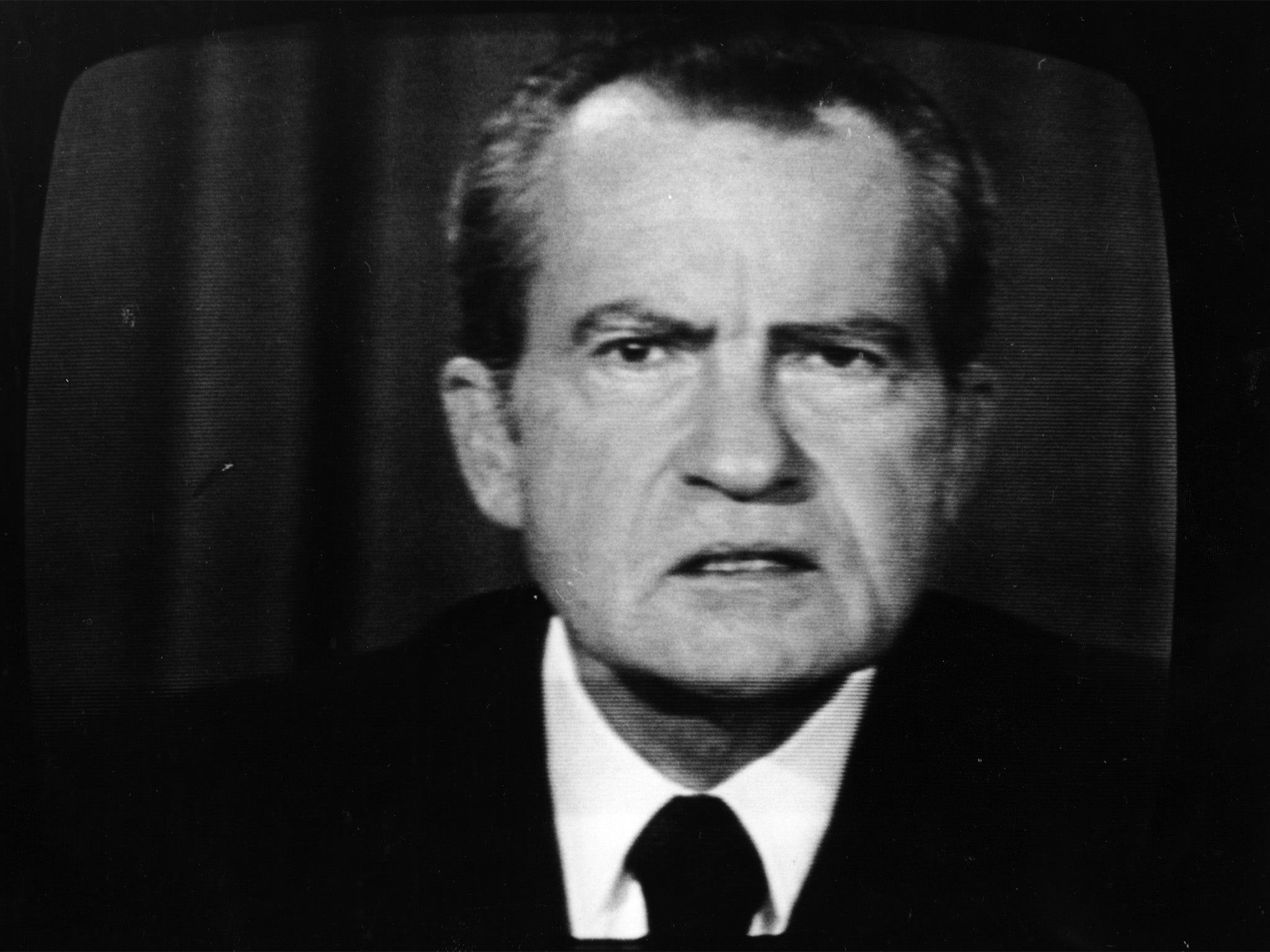

Watergate: Final secrets of Richard Nixon laid bare – by top aide Alexander Butterfield

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alexander Butterfield’s journey to the heart of political darkness began one November day in 1968, when he learned that his old UCLA college chum H R “Bob” Haldeman was running the transition team of president-elect Richard Nixon.

Then an air force officer on assignment in distant Australia, Butterfield was desperate to get back to real action, be it in Vietnam or in Washington DC. So he wrote to Haldeman asking for a job. He got one, beyond his wildest dreams. Haldeman, soon to be Nixon’s White House Chief of Staff, made Butterfield his deputy, in effect keeper of secrets for the man who kept the secrets of supreme power.

Now Butterfield is the focus of a new book by The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward, who with Carl Bernstein formed the reportorial duo who unearthed the Watergate scandal. The Last of the President’s Men, the book is called. The last man in terms of chronology perhaps, but now among the most interesting of Nixon’s top aides, and unarguably the most consequential.

Butterfield’s place in American history is guaranteed as the man who brought down a president, with his revelation of the existence of a secret White House taping system. Congress subpoenaed the tapes and Nixon was forced to hand them over. Without them, the president would probably have got away with it. Instead, the tapes produced the “smoking gun” – proof that Nixon had orchestrated the Watergate cover-up virtually from day one – that forced him to resign.

So much is on the public record. Less so, however, Butterfield’s personal memories of his four years in the White House, and the contents of dozens of boxes of documents he took with him when he left, and that he’s been keeping at his home near San Diego.

Yes, he was President of the United States, but in this moment, I just thought, the poor, pitiful son of a bitch

Both are now finally in the public realm.

Albeit in fragmented fashion, they capture Nixon in all his complexity: lonely, vindictive and deceitful, gauche and insecure to the point of paranoia, yet also displaying the odd flash of empathy, and an unarguable if perverse strategic brilliance. The ultimate contradiction was the obsessively secretive man who – apparently in order to create a reliable record in that pre-email era – installed the taping system that would destroy him.

Butterfield’s motives for disclosing it seem no less tangled: part desire to come clean; part the realisation that lying to Congressional investigators would send him to jail; and part out of a desire for revenge on a boss whom he privately dubbed Richard “I’ll get those sons of bitches” Nixon, and whose treatment of his wife, Pat, in particular appalled Butterfield.

At one point he was the “principal intermediary”, in Woodward’s words, between Pat and her husband. Nixon would often ignore her even as she spoke to him, burying himself in his famous yellow legal pads. At the winter White House in Key Biscayne, Florida, they had separate houses. She was, Butterfield believed, a “borderline abused wife”.

Not that Nixon was a philanderer. Butterfield recounts an excruciating 20-minute helicopter trip back to the White House from Camp David one Sunday evening. Nixon summoned a mini-skirted secretary to sit with his group up front. As she sat wedged between Butterfield and Nixon’s businessman crony Bebe Rebozo, Nixon began patting her bare legs, all the while carrying on small talk.

Her ordeal continued until finally Nixon stopped and turned to the window, staring out into the darkness for the rest of the flight.

“The poor, pitiful man,” Butterfield remembered. “Yes, he was President of the United States, but in this moment, I just thought, the poor, pitiful son of a bitch ....It was loneliness. It wasn’t a caress, it was simply a pat, pat, pat”.

The documents Butterfield took with him are shocking in a different way – none more so than a top-secret January 1972 memo from Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s national security adviser, updating him on developments in Vietnam. An angry Nixon scrawled on the memo that years of bombing had achieved “zilch”, and demanded to know why.

Fine, except that a few days earlier he had been on television, extolling the bombing. Later he would intensify it, to improve his re-election prospects that year. A small episode, but one that perfectly sums up both Nixon’s cynical duplicity, and the futile tragedy of the war.

Despite its title, this surely won’t be the last Watergate-related book. For decades, it’s been the scandal that keeps on giving. Just when it seems everything is known, down to the precise second of a Nixon sneeze on any given day, something else emerges. Perhaps, however, the Butterfield input is the last piece of living Watergate history.

Nixon, Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, Charles Colson and others of those most closely involved are dead. Active and handsome as ever, Butterfield is a splendid advertisement for the southern California climate. But he’s now 89. Of key Nixon aides, only the then White House counsel John Dean – he of the “cancer on the presidency” warning – is still alive.

So too are a few lesser lights such as Gordon Liddy, chief of the infamous plumbers unit and superviser of the break-in at Democratic Party headquarters, and a couple of the actual burglars, as well as the “dirty tricks” specialist Donald Segretti.

But Butterfield’s contribution is more relevant than ever now, as America gears up to choose a new president. Read this or any earlier book about Nixon, and one wonders: how could such a man have made it to the Oval Office? So bear with those countless profiles and investigations of the 2016 candidates. These too might unearth a smoking gun that spares the US another Nixon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments