Washington Redskins: 9 in 10 Native Americans not offended by name of NFL franchise, poll finds

Results show how few ordinary Indians have been persuaded by national movement to change team’s moniker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

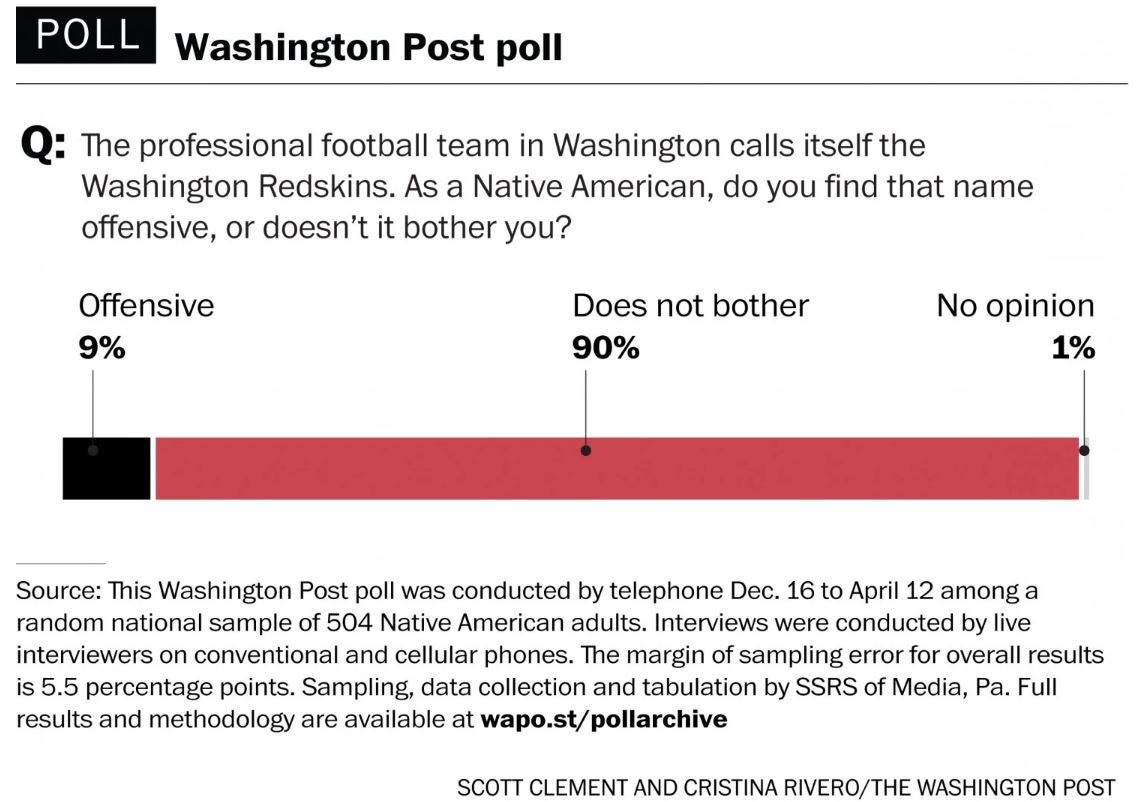

Your support makes all the difference.Nine in 10 Native Americans say they are not offended by the Washington Redskins name, according to a new Washington Post poll that shows how few ordinary Indians have been persuaded by a national movement to change the football team’s moniker.

The survey of 504 people in every state and the District reveals that the minds of Native Americans have remained unchanged since a 2004 poll by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found the exact same result. Responses to The Post’s questions about the issue were broadly consistent regardless of age, income, education, political party or proximity to reservations.

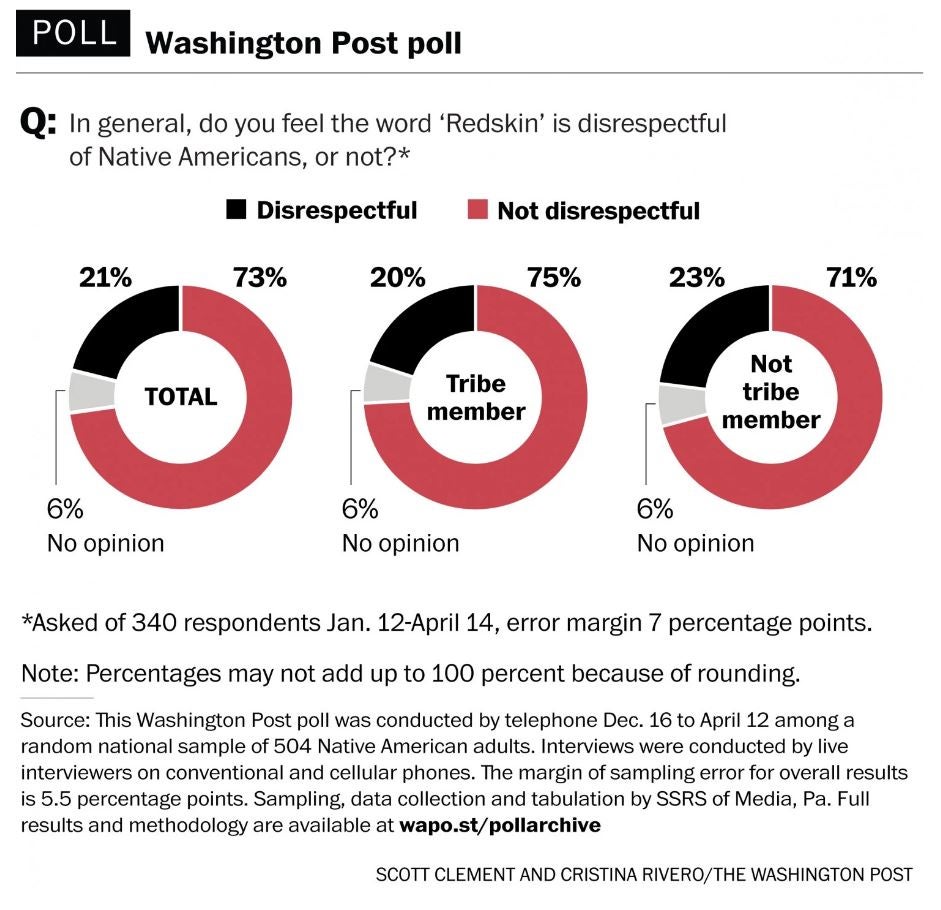

Among the Native Americans reached over a five-month period ending in April, more than 7 in 10 said they did not feel the word “Redskin” was disrespectful to Indians. An even higher number — 8 in 10 — said they would not be offended if a non-native called them that name.

The results — immediately denounced by one prominent Native American leader — could make it that much harder for anti-name activists’ to pressure team officials, who will almost certainly use the poll as further justification to retain the moniker. Beyond that, the findings might impact the ongoing legal battle over the team’s federal trademark registrations and the eventual destination of the Redskins’ next stadium. The name controversy has clouded talks between the team and the District, widely considered owner Daniel Snyder’s desired destination.

“I just reject the results” of the Post poll, said Suzan Harjo, the lead plaintiff in the first case challenging the team’s trademark protections. “I don’t agree with them, and I don’t agree that this is valid way of surveying public opinion in Indian Country.”

Since the nearly half-century-old debate regained national attention in 2013, opponents of the name have won a string of high-profile victories, garnering support from President Obama, 50 Democratic U.S. senators, dozens of sports broadcasters and columnists, several newspaper editorial boards (including The Post’s), a civil rights organization that works closely with the National Football League and tribal leaders throughout Indian Country.

Still, Snyder has vowed never to change the moniker and has used the 12-year-old Annenberg poll to defend his position. Activists, however, dismiss the billionaire’s insistence that the name is intended to honor Native Americans. They argue that he must act if even a small minority of Indians are insulted by the term — a dictionary-defined slur. They have also maintained that opinions have evolved as his unyielding stance has been subjected to a barrage of condemnation by critics ranging from “South Park” to the United Church of Christ.

But for more than a decade, no one has measured what the country’s 5.4 million Native Americans think about the controversy. Their responses to The Post poll were unambiguous: Few objected to the name, and some voiced admiration.

“I’m proud of being Native American and of the Redskins,” said Barbara Bruce, a Chippewa teacher who has lived on a North Dakota reservation most of her life. “I’m not ashamed of that at all. I like that name.”

Bruce, 70, has for four decades taught her community’s schoolchildren, dozens of whom have gone on to play for the Turtle Mountain Community High School Braves. She and many others surveyed embrace native imagery in sports because it offers them some measure of attention in a society where they are seldom represented. Just 8 percent of those canvassed say such depictions bother them.

Even as the name-change movement gained momentum among influential people, The Post’s survey and more than two dozen subsequent interviews make clear that the effort failed to have anywhere near the same impact on Indians.

Across every demographic group, the vast majority of Native Americans say the team’s name does not offend them, including 80 percent who identify as politically liberal, 85 percent of college graduates, 90 percent of those enrolled in a tribe, 90 percent of non-football fans and 91 percent of those between the ages of 18 and 39.

Even 9 in 10 of those who have heard a great deal about the controversy say they are not bothered by the name.

What makes those attitudes more striking: The general public appears to object more strongly to the name than Indians do.

In a 2014 national ESPN poll, 23 percent of those reached called for “Redskins” to be retired because of its offensiveness to Native Americans — more than double the 9 percent of actual Native Americans who now say they are offended by it.

A 2013 Post poll found that a higher proportion of Washington-area residents — 28 percent — wanted the moniker changed.

Oneida Indian Nation leader Ray Halbritter, a key figure and financier in the fight against Snyder, has described the issue as one of the most important facing his people.

“It is critical,” he wrote in a 2013 Post op-ed. “Indeed, precisely because it is so critical, this campaign is not going away, no matter how much the NFL or Snyder wants it to.”

But an overwhelming majority of Native Americans disagree, with just 1 in 10 saying they consider the issue “very important.”

“I really don’t mind it. I like it. . . . We call other natives ‘skins,’ too,” said Gabriel Nez, a 29-year-old Navajo who left his reservation last year to study criminal justice at a college in New Mexico.

“The name is nothing to me,” said Jarvis Michael Horn, a 39-year-old member of the Winnebago Tribe who works at a corner grocery store in Iowa.

“For me, it doesn’t make any difference,” said Charles Moore, a 73-year-old Oneida of Wisconsin who as a physician treated patients for four decades before retiring in Minnesota.

The poll, which has a 5.5 percentage-point margin of sampling error, was conducted by randomly calling cellular and landline phones. It asked questions only of people who identified themselves as Native American, after being asked about their ethnicity or heritage.

Those interviewed highlighted repeatedly other challenges to their communities that they consider much more urgent than an NFL team’s name: substandard schools, substance abuse, unemployment.

But Harjo questioned the validity of the poll results and said they do not reflect what she has seen during her decades of involvement with the issue.

“I don’t accept self-identification. People say they’re native and they are not native, for all sorts of reason,” she said. “The big picture is that [the poll’s finding] is totally opposite from my experience since the 1960s of where native peoples are today. And I know that from having a huge extended family in Oklahoma, in Nevada, in various states and across tribal lines. I know it from working with people who evaluate this kind of thing in their home communities.”

It remains uncertain how The Post poll will affect either the stadium discussion or the trademark case.

Although the Redskins have a lease at FedEx Field in Landover, Md., until 2027, team officials have acknowledged that they hope to relocate well before then.

Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan (R), Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D) and Washington Mayor Muriel E. Bowser (D) have all expressed interest in making a deal with the team. Hogan has defended the moniker, while McAuliffe has avoided criticizing it. Bowser and some D.C. Council members have publicly opposed it.

The mayor has stopped saying the name in recent years, and the council passed a 2013 resolution that condemned it as “racist and derogatory.” Though many who support the team say it should return to the site of RFK Stadium, where the Redskins used to play, the controversy has impeded negotiations.

News that such a large percentage of Native Americans do not care about the name could provide the necessary political cover for District leaders to welcome Snyder’s club as is.

The federal government, however, would also have to approve because RFK stands on National Park Service land controlled by the Interior Department. The current secretary, Sally Jewell, has echoed Obama’s opposition to the name.

In the trademark case, the team and two different groups of Native American activists have been fighting in various courts for the past 23 years over whether “Redskins” is disparaging and therefore ineligible for federal trademark protection.

Lower courts have said that Native Americans’ opinions on the term matters only between 1967 and 1990, when the team’s trademarks were registered.

Two years ago, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s appeal board ruled that “Redskins” offended a substantial number of Native Americans at the relevant time, violating the Lanham Act, which bars potentially disparaging names from trademark protection. A federal district judge upheld the order last summer. Now, the Redskins have petitioned the Supreme Court to weigh in, arguing that, regardless of whether the name offends Native Americans, the Lanham Act violates the team’s free speech rights.

Amid the legal maneuvering and name-change push, some Indians interviewed by The Post voiced resentment toward the activists. A small percentage of their community had, in their minds, spoken for the majority.

“It’s 100 people okay with the situation, and one person has a problem with it, and all of a sudden everyone has to conform,” said New York resident Judy Ann Joyner, 64, a retired nurse whose grandmother was part-Shawnee and part-Wyandot. “You’ll find people who don’t like puppies and kittens and Santa Claus. It doesn’t mean we’re going to wipe them off the face of the earth.”

But an important question remains: Is it appropriate for the name of a professional sports team to insult any percentage of a population that has historically been so mistreated by this country’s majority?

Officials with the National Congress of American Indians, the oldest and largest U.S. organization representing tribal communities, have argued that polls cannot settle moral issues.

“Changing the mascot of the D.C. team should not be determined by public opinion,” they said in a 2014 statement, though their leaders have often asserted that the opinion of tribal governments should matter.

The granddaughter of George Preston Marshall, the man who gave the team its contentious moniker in 1933, has made a similar point.

“It’s about respect,” Marshall’s descendant, Jordan Wright, told The Post two years ago. “If even one person tells you that name — that word you used — offends them, then that’s enough. That should be enough.”

Nowhere are the nuances of this complex debate more apparent than in a mobile home amid the mountains, rivers and forests on Montana’s Flathead Indian Reservation.

Rusty Whitworth, 58, is a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. A laborer who has worked on ranches most of his life, he does not mind the name.

“Just let them keep it,” he said of the team. “It ain’t hurting nobody.”

His wife, Anita Whitworth, 62, also belongs to the confederation. A mother of five who worked for years as a chemical-dependency counselor, she hates the name.

She views it much the same way that many activists do. They argue that the central problems ravaging native communities — poverty, violence and addiction — can only be fixed if young people take pride in who they are.

Her youngest, Whitworth said, is a dark-skinned 13-year-old who attends an almost entirely non-native school in a region long plagued by racial tension.

When she looks at him, Whitworth thinks back to the years of disparagement she’s endured.

She has seen store employees follow her because they suspect she will steal something. She has heard derogatory comments in restaurants.

She has also been called a “Redskin.”

“I don’t want to ever have my son experience anything like that,” she said. “It’s time to change. It’s time to move on.”

Ian Shapira, Emily Guskin, Jonathan O’Connell, Aaron C. Davis and Jennifer Jenkins contributed to this report.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments