What happened when Black Lives Matter came to a notorious KKK town in Texas

The people of Vidor have long complained that their reputation is outdated. Could a march for racial justice change people’s minds? Richard Hall reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The town of Vidor, in east Texas, has a reputation. It’s the kind of reputation that causes its residents to pause when someone asks where they’re from.

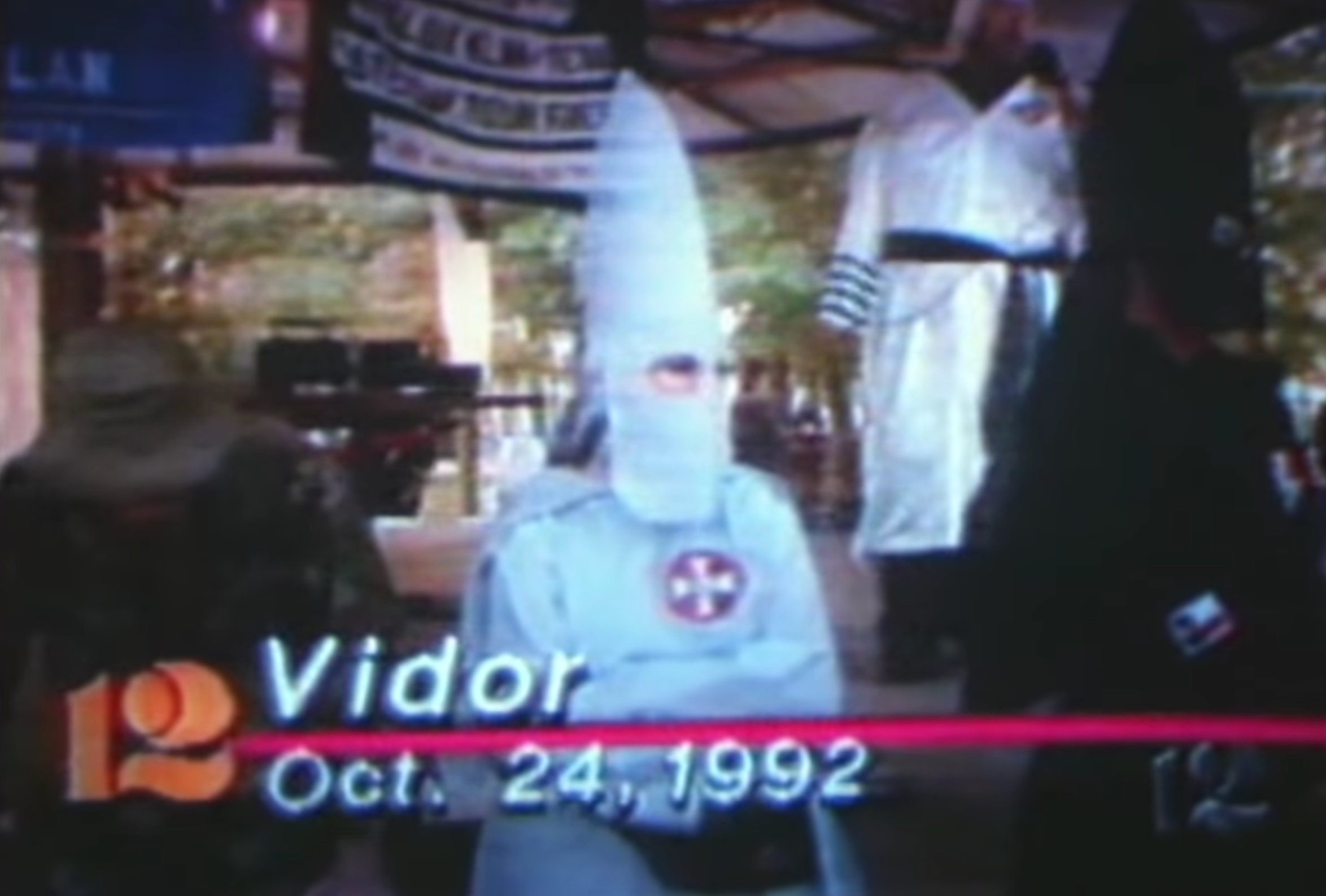

For years it was known as a sundown town – a place where non-whites were threatened with violence if they stayed after dark, and where they were barred from living through intimidation and discriminatory practices. It has a long history of Ku Klux Klan activity, and was once described by a local magazine as “Texas’ most hate-filled town”.

So when a notice appeared on social media earlier this month announcing a march would be held there in support of the Black Lives Matter protests, many believed it was a trap. “Do. Not. Step. Your. Black. Asses. Into. Vidor,” is how one black woman responded to a flyer posted on Twitter.

Even the person who organised the march, 25-year-old Yalakesen Baaheth, was aware of how improbable it sounded.

“There were a lot of conspiracy theories going around and I was like, yeah, you know what, this does look kind of suspicious,” she says, sipping on an orange juice in a Waffle House in Vidor.

But there was a purpose to holding the rally in such an ostensibly inhospitable place. The idea came from Baaheth’s friend, Maddy Malone, a Vidor resident. The two of them believed Vidor was better than the reputation that preceded it. By holding a march for Black Lives Matter, they could show their support for a cause they believed in and give the town a chance to show a different side of itself to the world.

“We got a whole bunch of responses from people in the town and the surrounding areas. There were some people in the town who were for it, there were some against it,” says Baaheth. “But I was gonna do it whether people liked it or not, because everybody deserves a chance to be heard and to show who they really are.”

Their march set off a collective soul-searching for the people of Vidor. For years, residents had complained that they had been unfairly singled out for the town’s dark past. They claimed that Vidor had changed. Those claims were about to be put to the test.

It would be easy to drive right by Vidor without noticing it at all. The coast-to-coast Interstate 10 runs right through the middle of the town between Houston and New Orleans. Someone making that journey might stop for gas or a rest and not realise a town lies beyond the strip malls that line the highway.

It sits 20 miles from the Louisiana border, and some say it bears more resemblance to that state than the rest of Texas. It is surrounded by swamplands that make the area prone to flooding, an occurrence that occasionally results in alligators ending up in people’s backyards (the tri-county area is home to an estimated half a million alligators).

It is overwhelmingly white – around 97 per cent according to the latest census. It’s also extremely poor. Some 20 per cent of its roughly 10,000 residents live in poverty – higher than the rate for Texas and the rest of the country. That poverty has brought with it the usual problems, among them a serious methamphetamine issue.

Much of the community is centred around the church; there is one on almost every street corner. Beyond that, it’s hunting, fishing and high school football.

Vidor was originally founded on the site of a lumber mill in the early 20th century, and took its name from the man who owned it. When the company left in 1924, the small community that had built up around it remained and gradually shifted to farming.

By the late 1950s its population numbered in the low thousands, but it grew significantly over the next two decades as the nearby oil city of Beaumont began to desegregate; Vidor became a “white flight” town, a home for white residents who moved from the larger and more racially diverse city next door.

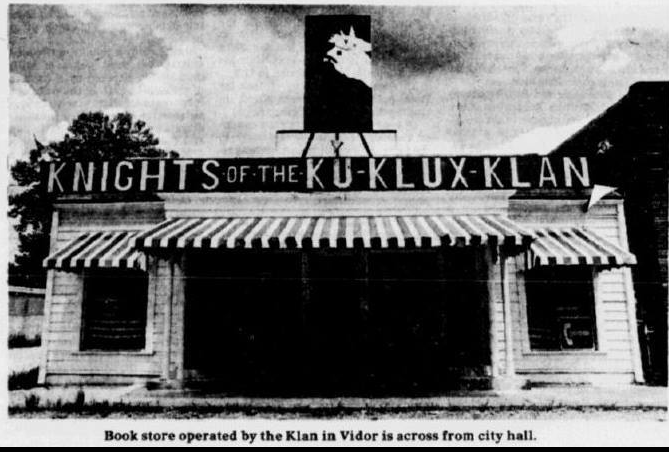

The Ku Klux Klan rooted itself firmly in the town. There were several competing chapters in the town throughout the Fifties and Sixties. The Klan even had a bookstore on the town’s main street. It used intimidation, violence and murder to keep out black residents, earning the town the nickname “Bloody Vidor”.

People in Vidor still talk about the billboard that was once placed on the highway as a warning, recalling some variation of the words: “N*****, don’t let the sun set on you here.”

The Klan’s visibility and strength in Vidor seemed to ebb and flow over the years. Locals speculated that its members moved away. Then, in 1993, it made its presence felt again when a federal judge ordered a housing project there to be desegregated. John DecQuir Sr was the first black adult to live in the town since the 1920s. His arrival was greeted by protests by Vidor residents and a series of public rallies and death threats by the Klan. They held one rally in the very same park where Baaheth and Malone would hold their peace march 27 years later.

Several more attempts to move in black residents were met with the same response. Locals blamed outside agitators brought in by a small minority of Vidor Klan members, but a media circus followed and Vidor’s reputation was sealed. Then, again, the Klan seemed to fade away. But Vidor held on to its reputation.

To this day, stories about racism encountered by black people in Vidor are commonplace. One of the top results for Vidor on YouTube is a video of a group of young, black men visiting the town for the day and experiencing several hostile encounters. The title is: “A day in the #1 racist city in America”.

Baaheth, who is planning to study audiology next year, lives in Port Arthur, a short drive from Vidor. Like everyone else who has lived near the town, she heard the stories growing up.

“When I was younger, we would go there a lot, but my family didn’t stop in Vidor,” she says. “We would not stop to get gas. We would not stop to go to the store. We would just go straight to my friend’s house.”

But over time, she says, she saw little changes that gave her hope.

“Whenever my parents would leave, I would go to the store with my friend, or if they needed to go to the mall, I would go with them. That really opened up my mind to seeing that not everybody is this type of way.

“We really generalise, especially if a town has a history of racial stigma. All those stories are true, don’t get me wrong, there is a difference between lies and truth. But at the same time, so much has changed.”

On 25 May, a black man named George Floyd was detained by a police officer in Minneapolis over an allegation that he had used a counterfeit $20 note. The officer, Derek Chauvin, handcuffed Floyd and pinned him to the ground with his knee on his neck. Despite Floyd’s persistent pleas that he couldn’t breathe, Chauvin held his knee there for more than eight minutes.

There can exist more than one truth. It is true that some people in this town are stuck in the dark ages, and it is true as well that there’s a whole generation trying to pull us out of it

Floyd’s death sparked riots that turned into mass protests across the country. Houston, where Floyd lived most of his life, was no different. Vidor is just an hour and a half’s drive away from Houston, but few expected the protests to reach here.

Baaheth and Malone wanted to show their support for the protests.

“[Malone] said: ‘Hey, I really feel like we should do a peace march in Vidor.’ And I was like: ‘You do know the reactions you’re gonna get, right? Are you prepared for the good and the very, very bad?’ She said she did and I said again: ‘No, do you really understand?’”

They were worried about the reaction of Vidor residents, they were worried about extremists who might try to harm people who took part, and they were worried about their friends and family.

The pair realised they needed some back-up, so they turned to a man named Michael Cooper, a pastor and president of the NAACP chapter in nearby Beaumont.

Cooper, 54, also grew up not far from Vidor, in a small town along the Neches River, on the outskirts of Beaumont. And he, too, remembers the stories about Vidor.

“We were kids in the Sixties and Seventies playing in the creeks on one side, and the people that were from this sundown town were on the other side,” he says. “We were all swimming in the same waters, but yet there’s a great divide.”

When Cooper first got the call asking him to come and speak at the march in Vidor, he says he was inclined to do what his father always taught him: don’t go to Vidor. His friends, mentors and family all told him the same thing.

“They asked me if I had a death wish,” he says. “My wife’s exact words were: ‘do you want to be a martyr?’”

“A lot of people have never heard of the phrase ‘sundown town’ – but we grew up with it,” he says. “Do not stop in Vidor and get gas. Don’t stop in Vidor if it’s dark. Do not stop in Vidor if the sun’s going down. And they would tell you that in the town, too. They were not afraid to tell you.

“Then I had to recall when my mother ran a small store she trained everybody over in Vidor. And when I worked over in Vidor. And I had to recall that when I sat in the pews at the First Baptist church in Vidor, and I was invited to meetings in these churches and I was treated very well.

“So, I had to go for the good folks and for the folks that wanted to make a difference. I really didn’t want to. I didn’t want to be the one that was offering the olive branch, but at the same time, I realised it had to be done. And I said, ‘if not me, who?’”

The days leading up to the march were full of trepidation for everyone involved. The organisers and participants were worried about violence from angry locals. Meanwhile, the locals were worried that violent protesters from out of town were coming to smash windows and destroy their businesses.

Most comments about the march on the town’s Facebook page were positive, but there were also some naysayers.

“This is the kind of thing that gets Vidor back in the news, next thing you know The Black Panthers will want to come march in Vidor again,” one user wrote.

“It’s organisations like BLM and Antifa that keep the racism fires burning. These are the true racist in this country. They get the media all fired up about it,” wrote another.

Another user responded to the smattering of posts with: “I’m tired of all these Ku Klux Karens.”

When the day came, Baaheth and Malone arrived at Raymond Gould Park just off the highway to see dozens of cars lined up.

“I was a little bit nervous, but to be honest I was ready to go. I don’t think I’ve ever been that pumped up before,” says Baaheth. “I was like, my God, people are really showing up.

“It made my nervousness go away to see how people were coming together. And I was like, this is it, we’re doing this.”

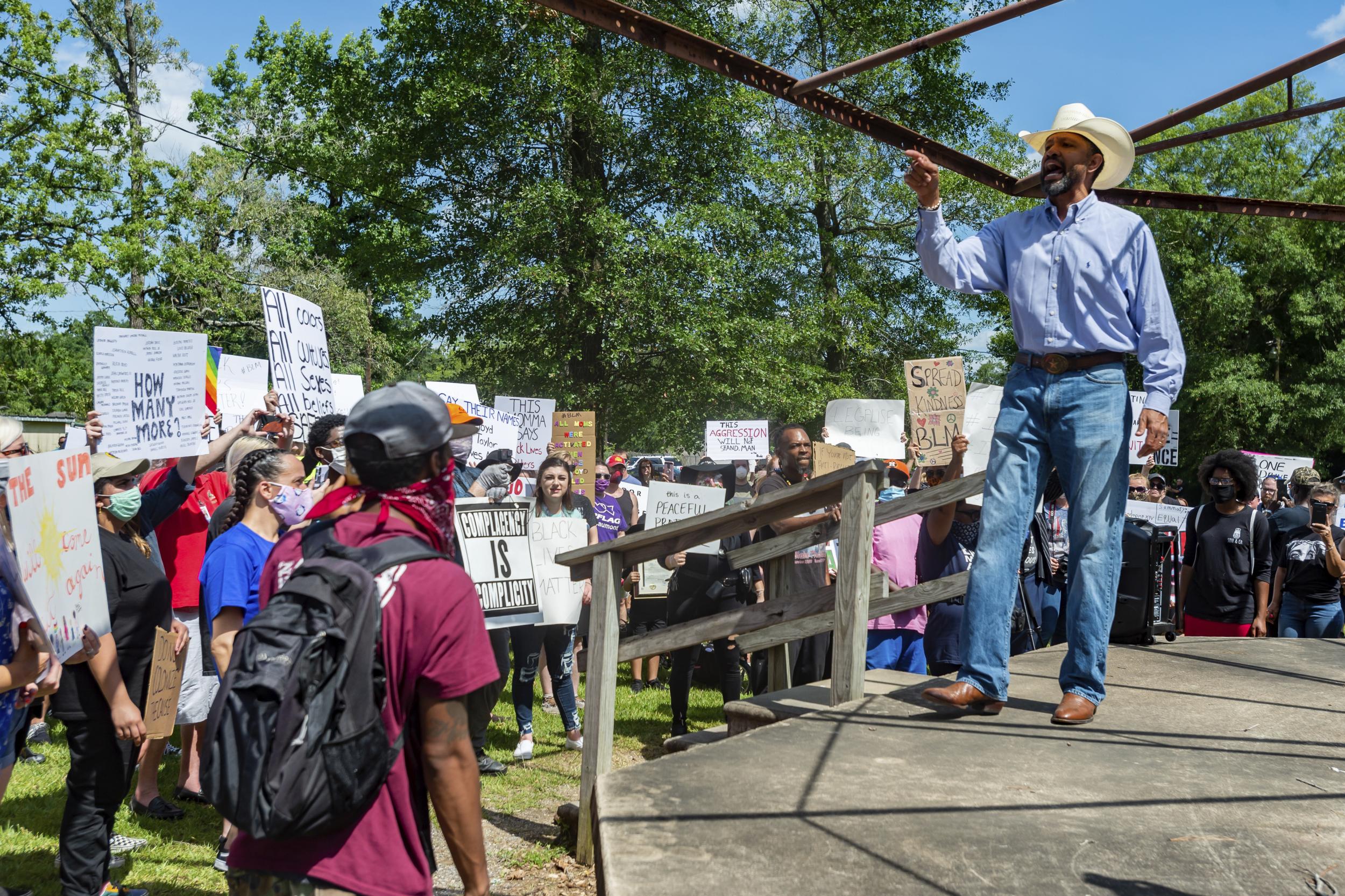

Around 200 people attended the march – some from Beaumont and the surrounding area, and some from the town of Vidor itself. One protester held a sign that read “Vidor can change too”.

In a speech that quoted the Bristol graffiti artist Banksy, Pastor Cooper declared in a booming voice: “This is history.”

“If nothing else happens in my lifetime, that happened and nobody can take it back,” he says of the event. “We can’t go back.”

On the other side of the park, a small group of armed white men describing themselves as “second amendment constitutionalists” stood guard over a veteran’s memorial. One counter-protester held a sign that read: “Vidor kneels only to God”.

The march passed without incident. But the soul searching continued after the protesters left. Almost everyone in Vidor saw the march as a test of the town’s reputation, one way or another.

“I am so sick of people saying our town is bad, racist and trashy. This is a good town and the people here love each other and I have not seen or heard anyone being treated like all those posts it’s all ridiculous and all lies,” wrote one woman, as the debate continued to rage on the town’s Facebook page.

The fact that it was no different to the thousands of other marches that have taken place across the country in the last few weeks, in itself, was seen by many as a victory.

News coverage of the march in Vidor noted the oddity of the march being held there at all. Texas Monthly, the same magazine that described it as “the most hate-filled town in Texas” in 1993, went with the headline: “Black Lives Matter Comes to Vidor – Yes, Vidor”.

A question hung in the air in the days after the march: what did it mean that Black Lives Matter had arrived in Vidor? Had this sundown town really changed?

For Rod Carroll, Vidor’s police chief, the march was proof that it had.

“I believe that every sinner has a future and every saint has a past,” he says in his office at the Vidor police department. “Yes there was in the Fifties a Ku Klux Klan here in Vidor. We’re talking 70 years ago. Seventy years ago there were a lot of things going on in America.”

Carroll is not a typical Texas police chief. He was born in New York and lived there until he was 10 years old, when his family moved to Dallas. His father-in-law, Jack Brooks, was a Democratic congressman for 42 years and helped to write the 1964 civil rights bill. (Brooks, who died in 2012, was in John F Kennedy’s motorcade when the president was assassinated.)

Carroll says there is no Klan activity in Vidor anymore (“I’m the police chief. I know something about it. They would want to chase me out of town”), and saw the march as a chance for Vidor to show what he believed to be its true face to the world.

“It wasn’t going to take but one idiot to show up and set us back 70 years,” he says. “But I had people coming up to me to thank me for providing security for the march. That was a powerful moment for me, and I believe it was a powerful moment for them. It really brought down some barriers.”

He believes that Vidor’s reputation has hung around so long partly due to journalists who come to the town looking for one thing.

“What they do is they find someone who represents the stereotype. A non-intelligent, toothless person. They go to the grocery stores and they get them. It’s easy to key in on us because we have a lot of poor people here,” he says.

“There is this perception that Vidor is very racist. My question is: tell me the last racist thing that went on in this community?

“We’re accepting of our past, but let’s be honest: what about the whole state of Mississippi? When you think of racism what do you think of in the 1950s? What about Alabama? What about Texas as a whole?”

*****

When Vidor residents talk about the problems the town has faced, they often talk in the past tense. The problem left when the Klan lost its sway here, they say.

“It’s an undeserved reputation,” says one woman, who did not give her name, at a beauty salon off Vidor’s main street. “My grandparents told me about how the Klan used to knock on their door and they would slam the door in their face.”

But for Vidor’s black and African American community, the small number that live there, the racism is still alive and well.

DeVon Noe, 24, was born and raised in Vidor, and still lives there today. He was among the speakers at the Black Lives Matter rally in the town. He introduced himself to the crowd as “Vidor’s resident gay black guy”.

Speaking to The Independent a week after the march, he says he was singled out for racial abuse from his first day at school.

“A group of students harassed me on the playground. They knocked me down and began to kick me while shouting slurs. And one stuck with me, ‘You’re a n***** and no one wants you here.’ The bullying continued on throughout my schooling,” he says.

“I’ve had bottles, beers, even food thrown at me while walking through town. People have jumped kerbs to try and clip me. I’ve been door-checked too many times.

“Racism is ever-present in Vidor. Those who deny its existence are willfully ignorant to the truth,” he adds.

Noe says he volunteered to speak at the rally to give his point of view as a person of colour and a gay man. And he thinks it might have done some good.

“I wanted to use my position in this community and speak on a subject most of the town wouldn’t know anything about.

“I believe that we as a community are making those strides to help others that know of our town and its past. That Vidor isn’t the image from the Fifties the media won’t let die. Yeah we got our few weeds but every town does,” he says.

James W Loewen has spent many years writing about and visiting sundown towns across the United States and authored a book called Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. Much of his work is focused on how sundown towns remain sundown towns.

“Generally it’s just racism, not organised into any kind of Ku Klux Klan. And not just only racists, but traditionalists, too. They are racist of course, but they can say: ‘Well, I’m just in favour of keeping the town the way it’s always been.’”

Vidor is like any other of the hundreds of sundown towns across the country, Loewen says. And many of them go through the same soul-searching as Vidor is currently experiencing.

“There are people who are perfectly happy with having the reputation they have. Then there are people who no longer want to be known as a sundown town. And then there are people who want to no longer be a sundown town,” he says. “And that’s quite a difference, if you see what I’m saying.”

Still, he adds that the march in itself was a sign of progress.

“It shows that there’s more than one person, that is to say, it shows progressive-minded people in the town that there’s a mass of people who think this way, and that’s wonderful.”

*****

Whitney Murdock, a 30-year-old mental health responder who lived in Vidor until last month when she moved to Beaumont, is one of those progressive-minded people who waited a long time to see change.

She went to the march along with a few friends, much for the same reason as everyone else.

“I know Vidor’s reputation, and we still have a reputation for a reason. I know it’s not gone. I know that prejudice is still very much alive,” she says. “And I know in some of the deeper, darker corners, the KKK, Ayran Brotherhood, all those types still exist.

“But I feel, and I think we kind of showed people the other day at that march, that there is a new generation wanting to take over and wanting to get away from that.

“And that’s one thing I would really like people to understand – that there can exist more than one truth. It is true that some people in this town are stuck in the dark ages, and it is true as well that there’s a whole generation trying to pull us out of it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments