Desperate Venezuelans swarm over the border to buy food

As Venezuela's economy collapses under the weight of galloping inflation and mismanagement, its people descend on neighbouring Colombia in search of sustenance and daily essentials

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It wasn't much, but it was all she could afford – a sack of laundry detergent, a package of tampons and 18 rolls of Colombian toilet paper. Marys Rosalba was carrying the prized goods back to Venezuela with a tight grip and a fierce look that said: "Don't even think of trying to rob me."

The three items had cost her an entire week's wages. “I used to have my own little market,” said Rosalba, 50. “Now I clean houses from 6am to 7pm. When I'm not standing in line.”

Up ahead on the bridge over the Táchira River was the border checkpoint, and on the other side an oil-rich country of empty cupboards and supermarket queues stretching for blocks.

Cúcuta, long known as a city of contraband goods, has suddenly became a lifeline for desperate shoppers in neighbouring Venezuela, and one of the starkest illustrations yet of its panicky, gnawing hunger.

Tens of thousands of Venezuelans like Rosalba have streamed across the border for basic goods in recent weeks as their country's economy collapses under the weight of the world's highest inflation rate and chronic mismanagement, which has produced shortages of everything from nappies to milk.

Just days before Rosalba made her meagre purchases, more than 120,000 Venezuelans poured across the border as both countries agreed to briefly reopen several crossings that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro ordered shut last August. An additional 35,000 shoppers did the same on July 10.

“They used to come here to sell. Now they come to buy,” said Colombian shopkeeper Viviana Lozano, who had to hire 10 friends to cope with the crush of shoppers. She needed a money-counting machine to process their giant wads of Venezuelan bolivars, whose largest-denomination bank note, a 100 bill, is worth less than a penny.

“It was too crazy,” Lozano said.

Some Venezuelans travelled hundreds of miles through the night on long-distance buses to swarm through the crossing during the weekend openings. They hugged Colombian border guards and went racing for the supermarkets. Stuffing suitcases and duffel bags with as many items as they could fit and their bolivars could buy, they went home with sacks of rice, sugar, corn meal and milk powder, like sailors preparing for a long voyage at sea.

It was a short reprieve. In recent days, border traffic has been much more limited. Colombian authorities – worried the growing crowds could spiral out of control – say they want to end the ad hoc crossings and reopen the border on a long-term basis.

Both governments say they are in negotiations to do so, although Maduro officials have bristled at the Colombians' depiction of Cúcuta as a “humanitarian corridor”. They insist the claims of spreading hunger are part of a smear campaign by Venezuela's opposition.

Over there, you wait in line all day for a kilo of rice and sometimes it runs out before your turn comes, so it's all for nothing

But on Cúcuta's border bridges in recent days, where a smaller but steady trickle of people are allowed to pass, stories of hardship and indignity appeared to be the only thing in abundance. Venezuelans with doctors' notes, children enrolled in Colombian schools and Venezuelans with dual nationality were among the lucky ones still allowed to cross.

The Venezuelan economy is projected to shrink 10 per cent this year, according to a recent International Monetary Fund report, and consumer prices are clocking up a 700 per cent increase.

“Over there, you wait in line all day for a kilo of rice and sometimes it runs out before your turn comes, so it's all for nothing,” said Carlos Ortega, 68, a retired geology professor trudging back home after a doctor's appointment in Colombia. His Venezuelan pension was good for only a few pounds of Colombian beans, sugar and flour.

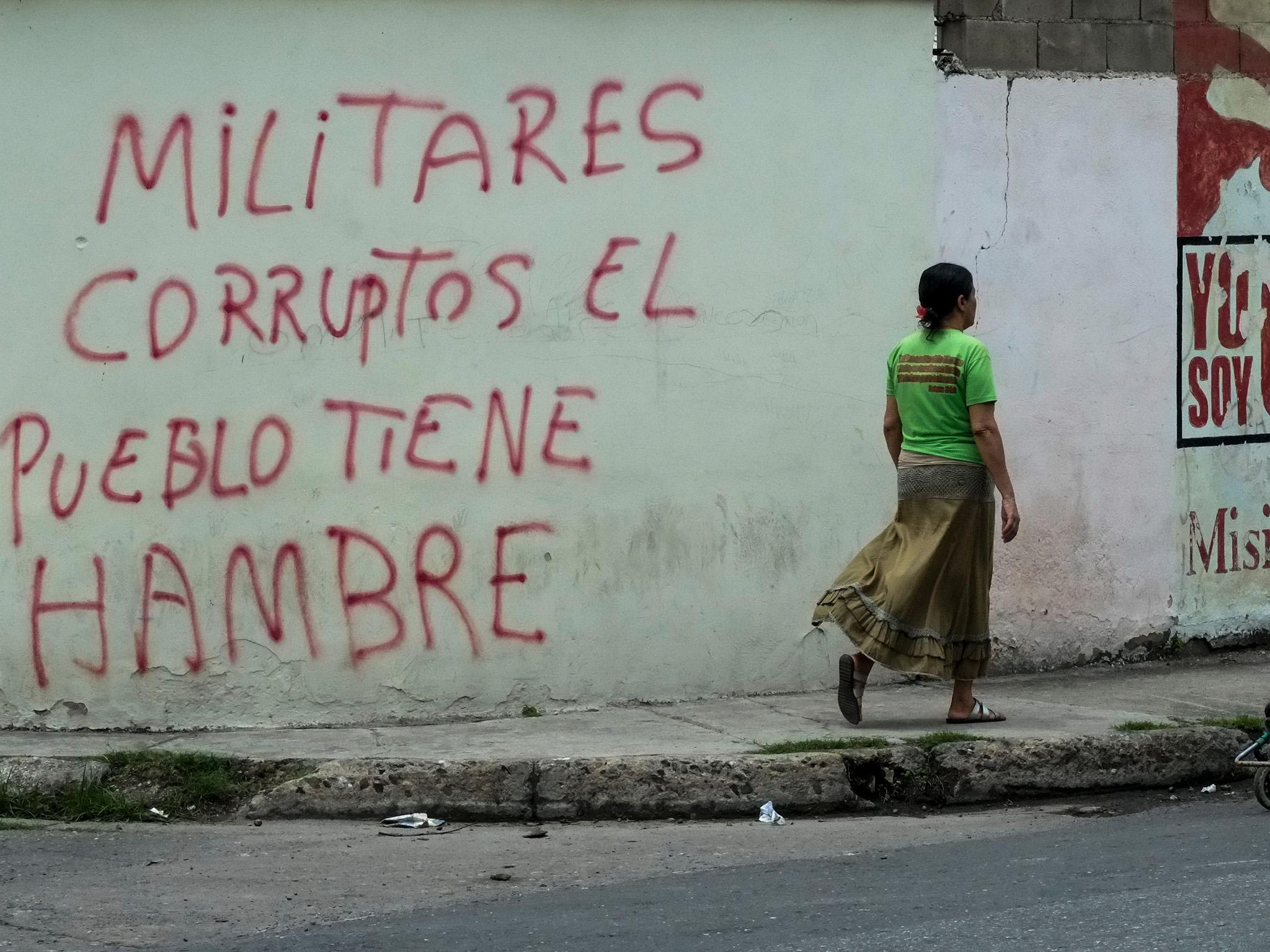

“This government has looted our country,” he said, glaring at the Venezuelan border guards. “And they're still doing it. I've never been hungry like this."

Maduro ordered the border closed after three Venezuelan soldiers were injured in a shootout last August with alleged smugglers. The President claimed that as much as 40 per cent of Venezuelan goods were being leeched out of the country by people seeking to take advantage of how cheap they are, thanks to the socialist-inspired government's subsidies and price caps. But those same policies have contributed to shortages that have grown ever more severe as low oil prices crimp Venezuelan government finances, limiting the import-dependent country's supply of basic items.

Carlos Luna, president of the Cúcuta Chamber of Commerce, said the surge of Venezuelan shoppers this month was a burst of business for Colombian vendors, “but that's not the kind of border that we want”.

Luna said he expected the border would be permanently reopened within 15 days, and that both countries were more committed to cooperation on enforcement.

But nearly a year after Maduro launched his crackdown, the economic incentives that make smuggling so lucrative are unchanged. The contraband trade appears to be primed for a new boom when the border reopens and cars and buses once more stream across, something that could make Venezuela's scarcities even worse.

Venezuela's military deployment at the border has slowed, but not stopped, the flow of goods into Colombia. Just a few hundred yards upriver from the official crossing, Venezuelans wade through the shallow river in plain sight of armed Venezuelan border guards. They'll look the other way for a small bribe, according to residents here. The footpaths and motorcycle trails through the riverbed reek of gasoline, carried over after dark in six-gallon plastic jugs called “pimpinas”.

Venezuelan government service stations sell top-quality high-octane gasoline for 2 cents a gallon. On the Colombian side, grizzled old men sit in the shade along the roadways selling pimpinas at $10 a pop, waving their funnels at passing motorists. At the wholesale market in central Cúcuta, huge piles of containers of powdered milk stamped with the Venezuelan government's “Mercal” label were being unloaded in broad daylight.

Carolina Higuera, 34, who runs a money-changing operation at the border, noted how the economic crisis in Venezuela had altered the long-time dynamic between the neighbouring nations.

For as long as she could remember, “Venezuela was the rich country, and Colombia was poor. People went there to find jobs. Now it's the other way around,” she said.

Venezuelans' bolivars have depreciated so fast that many who arrive in Colombia find they can't stock up on much. Venezuela's currency has lost more than 90 per cent of its value in the past two years.

Several Venezuelans, including Rosalba, the house cleaner, said they weren't getting enough to eat, admitting that many of their meals now consist of little more than cornmeal cakes and fruit. “I'm 50 years old, and I've never been hungry like this before,” she said.

Venezuela's crisis does not yet appear acute enough that its citizens are descending on Colombia in large numbers as refugees. But there is nearly universal resentment here about a rigidly controlled border in a region that has never had one, and where Colombians and Venezuelans are used to living, working, shopping and marrying on either side.

Benedicta Vera, 57, had moved to Venezuela three decades ago. Marxist FARC guerrillas drove her family from their small farm, she said, and the four youngest of her 14 children were born in Venezuela. It was too hard to think of moving the whole family back and starting over again in Colombia.

“It can't go on forever like this,” she said. “At some point it has to end.”

After a day of cleaning houses on the Colombian side, she walked toward the Venezuelan checkpoint, carrying little more than a bag of sugar and a sack of rice.

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments