Turnout spiked among younger voters in the last three elections. This is what’s needed for that to be repeated in 2024

Elections coordinator Ruby Belle Booth tells Gustaf Kilander there’s an ‘opportunity between now and 2024 to make sure that every single young person has the information and resources they need to get registered to vote and to cast their ballot’

Long thought to have given up on politics and given in to apathy, the political activity of younger people is now surging.

In 2018, the first election since former President Donald Trump’s 2016 win, turnout spiked among younger voters, with almost double the number of those in their late 20s and early 30s taking part compared to the previous midterms in 2014.

Younger voters strongly supported the Democratic Party, helping them take back the House in 2018 and the Senate after the Georgia runoffs in early 2021, but it was unclear if the spike in participation would carry on after Mr Trump left the White House in January 2021.

Taking into account the 2022 midterms where Democrats held onto the Senate and lost the House by a smaller margin than expected, the progressive research firm Catalist states in a report that “Gen Z and Millennial voters had exceptional levels of turnout, with young voters in heavily contested states exceeding their 2018 turnout by 6% among those who were eligible in both elections”.

Similarly, the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University released an analysis shortly after the 2022 midterms stating that “young voters in Arizona, Nevada, Georgia, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania gave Democratic candidates a winning advantage in close races”.

In Arizona, Democrat Katie Hobbs beat Republican Kari Lake by 17,117 votes in the governor’s race.

“Young people provided a net of 60,000 votes toward” Ms Hobbs, handing her the win, according to CIRCLE.

In the Nevada senate race, young voters backed Democrat Catherine Cortez-Masto at a rate of three times her margin of victory.

In the Georgia senate race, younger voters gave Democratic Senator Raphael Warnock 116,000 net votes against Republican nominee Herschel Walker in 2022. Rev Warnock received just 35,000 more votes in a race that moved ahead to a runoff where the Democrat retained his seat.

In Pennsylvania, Democratic Senator John Fetterman beat Mehmet Oz by about 190,000 votes with young voters providing him with a net 120,000.

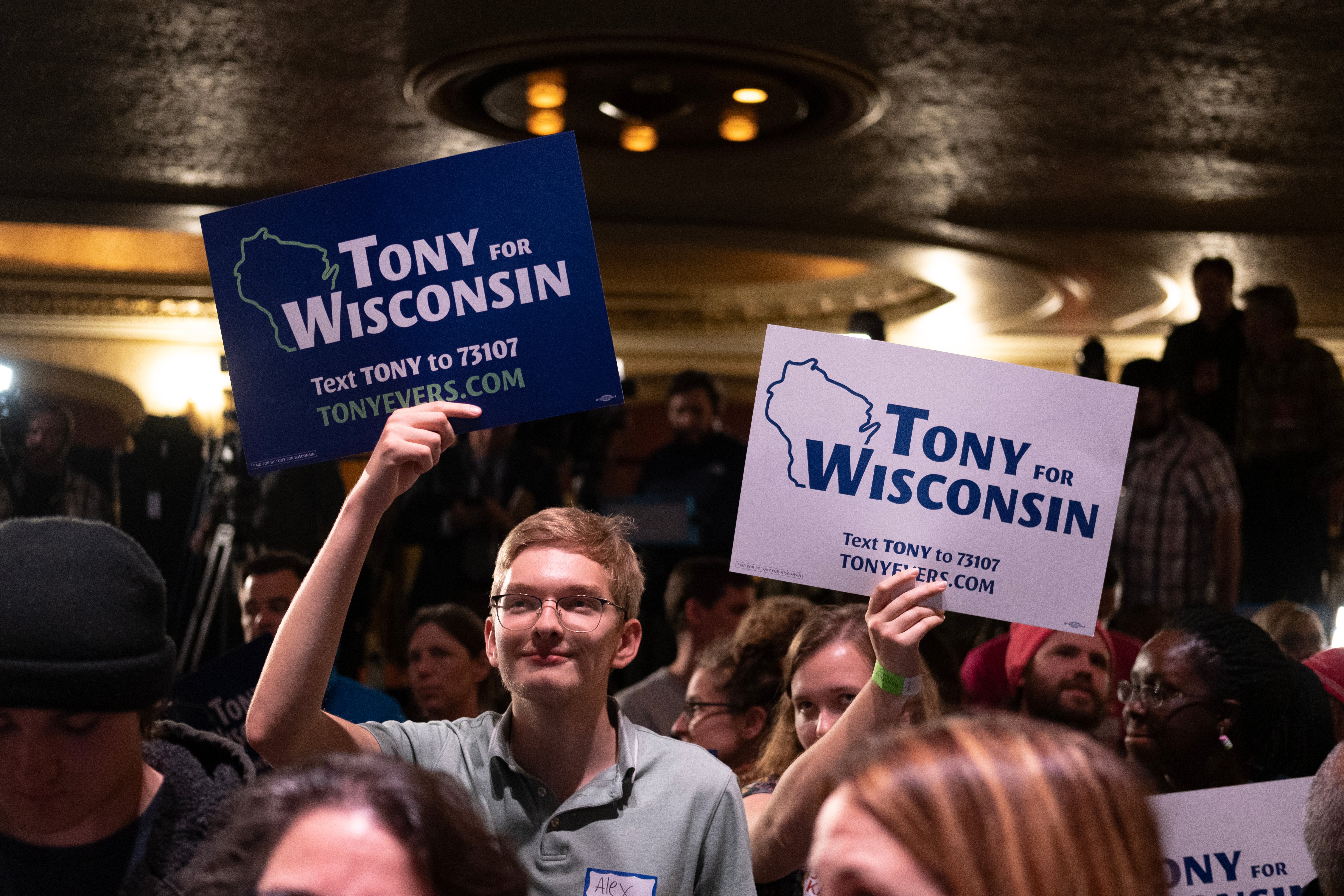

Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers won re-election by 89,000 votes as young voters cast a net 79,000 ballots in his column.

“In close elections decided by just a few percentage points, young voters can be more than influential: because of their often vastly different vote choice compared to older voters, they can be decisive,” CIRLE writes.

The lead author of that study, CIRCLE elections coordinator Ruby Belle Booth, tells The Independent that “we’ve been seeing over these last three cycles a new generation that’s really finding its political voice.

“And if you think about when their civic development has been happening, they’ve had access to smartphones and the internet and social media that’s given them both unprecedented access to information and also connecting them with one another.”

But she goes on to note that these voters have become adults in an age of extreme partisanship and political strife – often involving issues that are important to them such as the climate crisis and gun violence.

“Our research shows that they really see the power in their own voice,” Ms Booth says.

Catalist found that “65% of voters between the ages of 18 and 29 supported Democrats, cementing their role as a key part of a winning coalition for the party”.

“While young voters were historically evenly split between the parties, they are increasingly voting for Democrats. Many young voters who showed up in 2018 and 2020 to elect Democrats continued to do the same in 2022,” the research company added.

According to the US election project operated by political scientist Michael McDonald at the University of Florida, 111 million votes were cast in 2022 compared to 118 million in the previous midterms in 2018.

“In the last few elections, in particular, I think there have been these issues that have really been motivating young people and getting them to the ballot box more so than … particular candidates or the influence of political parties,” Ms Booth says.

This “issue engagement” and organising spearheaded by young people has helped increase turnout among younger voters, she adds.

Speaking about the 2018 midterms, Ms Booth mentions the Parkland school shooting, saying that gun control was a “major motivating force”.

“Young people who said that they supported or were actively involved in the post-Parkland movement were 21 percentage points more likely to say they voted, which I think just goes to show that connection between issues and organizing and turnout,” she says. “In 2022, I think that issues, again, like gun control and abortion and climate and student loan debt brought people out to the polls.”

“It’s not just that young people care about gun violence and gun control – it’s that there have been these youth-led movements to get young people to connect those issues to elections and to voting,” she adds.

CIRCLE found after the 2022 midterms that “Young voters are more likely to trust elections and feel democracy is secure, as well as to identify as independents”.

Optimism about the future is also higher among younger voters compared to their older counterparts.

“In 2022, one of the big pushes, especially with ... older Democratic voters ... was that this is a chance to save democracy because there are all these candidates who are … threatening democracy. And I think that that isn’t necessarily something that young people really connect to because they haven’t necessarily seen democracy functioning super well historically because of this partisanship and not seeing action on the issues that matter to them,” Ms Booth says.

She adds that younger voters are less likely to be swept up in the culture war and in partisan arguments because they “just want things to get done that will provide them with a healthier, healthier, happier, better life”.

When asked if younger voters are motivated to go to the polls more by fear and anger rather than optimism, Ms Booth notes that following the 2018 election, CIRCLE found that young people who were more cynical about politics were more likely to vote.

“But I don’t think that necessarily means that everyone is going to the polls from a place of total cynicism,” she says, adding that seeing political accomplishments that further their interests means they’re “going to be coming to the polls with a bit more optimism and hope”.

“There’s going to be times when they’re enraged and want to make sure that their rights are being protected. I think it is really circumstantial, and I’m not sure that we have the data to answer which is more motivating because I think it will depend on every young person and the state that they’re in and the political dynamics that that they’re going through,” she adds.

A CIRCLE survey released earlier this year found that 55 per cent of people between 18 and 29 believed that the country is moving in the wrong direction while only 16 per cent believe it’s on the right track. Twenty-eight per cent were unsure.

Asked if millennials are bucking the trend of voters growing more conservative with age, Ms Booth says: “The one thing I always come back to when talking about that sort of trend … is that the lives that millennials are leading now are really different from the ones … that boomers were when they were the same age”.

She adds that a number of the “milestones” that are seen as being a part of becoming more conservative, such as getting married or buying a house, “millennials relate to differently because they have a different relationship to the institution of marriage”.

“They also have a really different economic situation and it’s going to be a lot longer before most millennials are able to buy a house,” she says. “I’m not sure if that is actually impacting how they’re experiencing their political beliefs but I think it’s hard to ignore the fact that there are these very real differences.

“I’m not surprised that we would see that bear out in their political leanings as well.”

She sees that trend continue with Gen Z. “Millennials were more diverse, more progressive, and in some ways more engaged than Gen X when they were young. And I think we’re seeing that now” with Gen Z.

Members of Gen Z were first able to vote in the 2018 election, “and we did see that huge bump. Whether that was all Gen Z is impossible to say,” she says, adding that younger voters are making the electorate trend more liberal and more engaged.

“But it’s hard to say if that’s an overt difference between Millennials and Gen Z or if … they’re just new young people in the fray,” she notes.

While the political activity of younger voters is on the rise, older voters still have them beat in terms of turnout.

According to the Brookings Institution, in the 2022 midterms, “18- to 29-year-olds showed a noticeable decline in turnout since 2018, with the oldest group (over age 65) registering a modest gain”.

In the 2018 and 2022 midterms, more than 30 per cent of 18-29 year-olds voted, compared to around 20 per cent in the 2014 midterms. Among those 65 and above, more than 60 per cent voted in both 2018 and 2022.

Brookings noted that “as in the past, older eligible voters displayed higher turnout rates overall than younger eligible voters”.

Ms Booth says that “There’s a lot of barriers to voting that young people face that older people don’t … things like policies that get rid of early voting and policies that limit mail-in voting and policies that make it harder to register to vote”.

Younger voters are “more likely to move around a lot … which can make it harder to update your registration and to follow the different local rules about voting and elections”.

“I think a lot of older adults are like, ‘Oh, voting is easy’ – Yeah, it’s easy if you’ve done it a million times,” she adds. “But if you’ve never registered to vote before, you don’t know what a county clerk is, it can be not only challenging to find that information but also really intimidating.”

A CIRCLE analysis from earlier this year states that just “half of youth say they’re ‘as well-informed as most people’ and only 40 per cent say they feel well-qualified to participate in politics”.

“I think that young people don’t want to make uninformed votes and they definitely desire more information,” Ms Booth says.

“I think there’s a tendency to be like, ‘Oh, well, young people don’t vote because they don’t care’ – But I think it’s a lot more likely that it’s because they are facing these barriers, whether it’s because they just literally don’t know how to register because nobody’s ever told them or they don’t think their vote or their voice matters because no one’s ever told them it does,” she adds.

Ms Booth said there’s an “opportunity between now and 2024, to make sure that every single young person has the information and resources they need to get registered to vote and to cast their ballot.

“It’s also about building this confidence and building this self-assuredness and sense of self-efficacy – there are over eight million young people who are going to turn 18 between 2022 and 2024. And I think that they really represent this opportunity to get young people engaged.

“They’ve never done this before. It’s going to be their first presidential election … So we can either have a huge investment in making sure that those young people get the information they need, or we can fail to invest and they won’t be given the tools and information they need to turn out.”

“If that happens with 18,19 year-olds, and with 18-29 year-olds who are still building that habit of voting, I think you’re going to be a lot more likely to see that young people don’t turn out as much in 2024,” she cautions. “If we’re showing up for young people between now and 2024, then young people will likely show up at the ballot box and once again prove to be this really influential force but they’re not just going to do it without the support and the organizing that’s been happening for the last six years.”

“Young people have this tendency to really be focused on issues ... and less on the broader political landscape … but if Trump is on the ballot in 2024, I think that will be a different story,” she notes.

Ms Booth says that the issues young voters tend to care about are “closely intertwined with their lives and their identities” mentioning the movement for racial justice in 2020 and the struggle for reproductive rights in the wake of the Supreme Court striking down Roe v Wade.

“I think for young women, it’s easy to feel like your very self-hood is under attack when that’s being threatened and for other young people who may see the restrictions on abortion as a win because there’s also plenty of anti-abortion young people – they’re seeing their religious beliefs or moral beliefs really tied up in these political issues,” she adds.

The elections coordinator says the internet and social media shouldn’t be relied upon as the “main place that young people get their information because some people’s TikTok feeds are going to be all politics and other people’s are going to have no politics, and that’s just how these algorithms work”.

This is why it’s important for other groups and institutions to step up to “serve as a political home” for younger voters, she adds.

“Some young people live in families and communities where everyone’s talking about politics and others live in communities where no one’s talking about politics. So there are a lot of different factors that can be feeding into if people are actually informed or not. I think it’s not a given that just because the information exists on the internet they’re going to necessarily know to even look for it.

“The young people who didn’t vote in 2022 – 38 per cent said they forgot or were too busy, which can be solved with more information – more people telling them when the election is, or with policies that provide opportunities for things like early voting and absentee voting,” she notes. “Thirty-two per cent said they didn’t think it mattered or it wasn’t important to them … I think we can we can fix that with information as well.”

“When you’re looking at a midterm election … there are also all these local elections that can be really confusing and hard to understand like what even is a lieutenant governor – I think a lot of young people haven’t learned about that in their schooling,” Ms Booth adds.

She notes that the “information ecosystem” gets more challenging as you move towards more and more local issues.

“I think about my local news, so much of it is behind a paywall that if I’m a young person, I’m not going to know who’s running for city council,” she says.

“Some young people, they’re going to hear about voting and registering to vote in school and they’re going to jump at the opportunity, other young people … they’re going to be less likely to vote because they hate school.

“So it’s really important that they have multiple places where they’re hearing about voting and elections, to help to start to build that self-efficacy and that feeling like they actually are qualified,” she adds.

Asked if 2024 ends up being a Trump v Biden rematch will lead to a spike in young voter turnout, Ms Booth says, “I think about this every day – I have no idea”.

“I think the difference is going to be made if these political leaders are speaking to young people and talking about the issues that matter to them and bringing them on as staffers on their campaigns and having outreach not only to the young people who are easy to access, like the young people on college campuses – but going beyond that and making sure that every young person, whether they’re in college or not, no matter their background, no matter where in the country they are, that they’re being spoken to and being heard,” she says.

“I think it’s so hard to play this prediction game because when it comes to young people, it really depends on what a lot of other people are doing.

“Traditionally, we see that the Democratic Party and Democratic campaigns do a better job of reaching a diversity of young people … but that doesn’t mean that that can’t change. And it doesn’t actually reflect what’s happened so far this election cycle.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks