1921: The year America inaugurated its other worst president

Warren G Harding is usually at the bottom of the presidential ranking… until Donald Trump came along, that is, writes Andrew Naughtie

Joe Biden’s presidency has been born under a bad sign – or rather, amid the largest and most urgent security risk to threaten an incoming president since the Civil War. With 25,000 troops stationed in the nation’s capital to protect it from an extremist insurrection, what’s coming may yet dwarf even the destructive spectacle of the Vietnam War and civil rights.

Does this make Donald Trump the worst president of all time? Many are already saying so. But for that title, he is competing with 44 other men – and by many historians’ reckoning, one of them in particular deserves the gong.

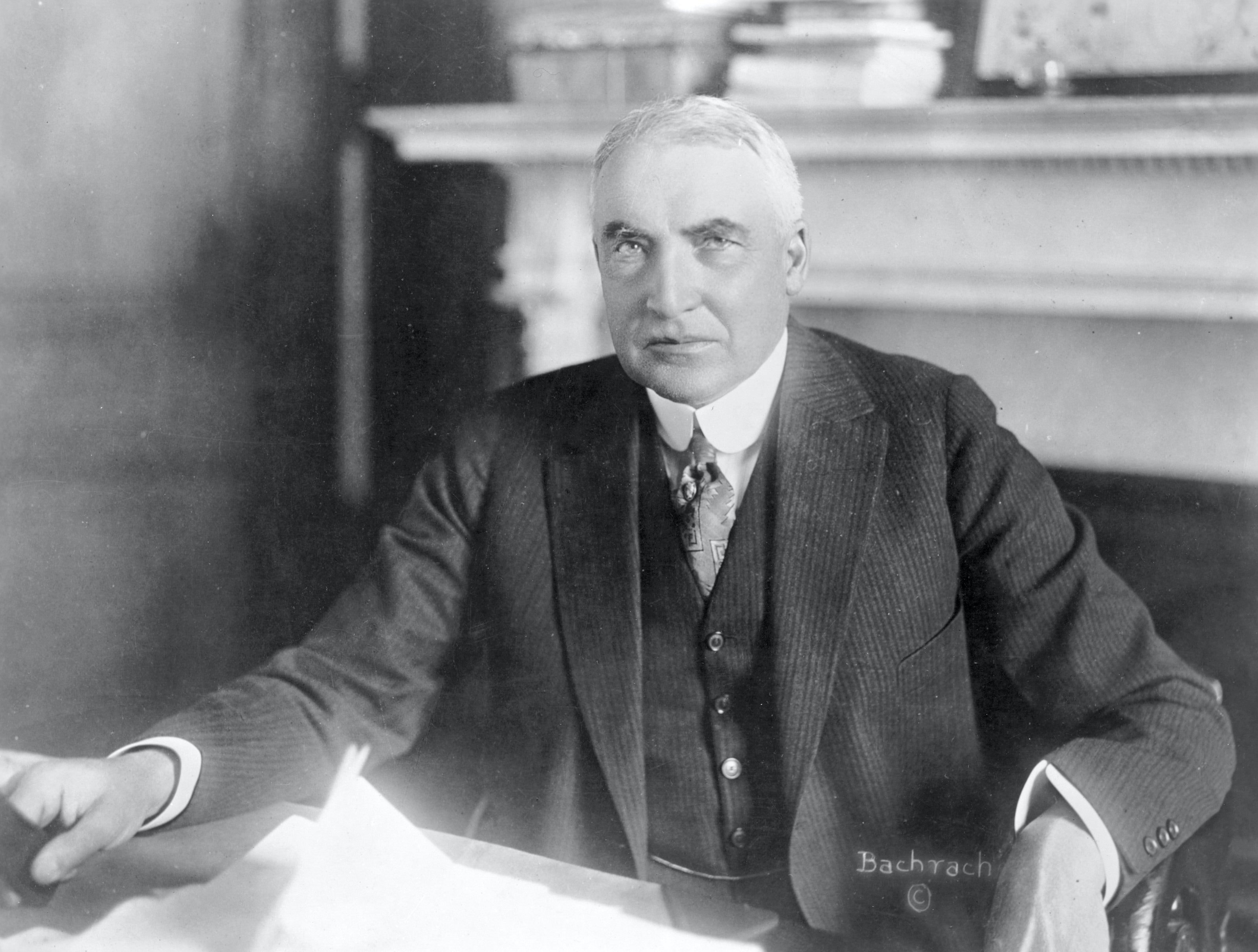

A hundred years ago, the US inaugurated Warren G Harding, who ultimately held office for two-and-a-half years before dying at the age of 57 – and who once summed up his presidency in a single sentence: “I am not fit for this office and should never have been here.”

A respected and well-liked and one-term Republican senator from Ohio, Harding won the Republican nomination thanks to intricate manoeuvres at a divided national convention; from there, he was elected to succeed Democrat Woodrow Wilson, who had taken the US into the First World War – a choice that many in the US had come to loathe.

Riding a backlash against Wilson, the war and the reforms of the Progressive Era in general, Harding promised the US “a return to normalcy” – an odd choice of words for which he was widely mocked – and trounced his Democratic rival, James M Cox.

Once in power, he presided over a corrupt government whose true venality only became clear after his death. Historians have long condemned him for failing to use the powers of the presidency to the full. He regarded it as a primarily ceremonial role, and brought no particular vision or ambition to it; he also failed to rein in cronies and appointees who exploited the positions he granted them.

The result was a level of political scandal unlike anything seen in decades. The so-called Teapot Dome affair, which involved the illegal transfer of oil leases on federal land by Harding’s interior secretary, Albert Bacon Fall. The scandal grew so large it eventually reached the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Harding administration had handled the leases illegally.

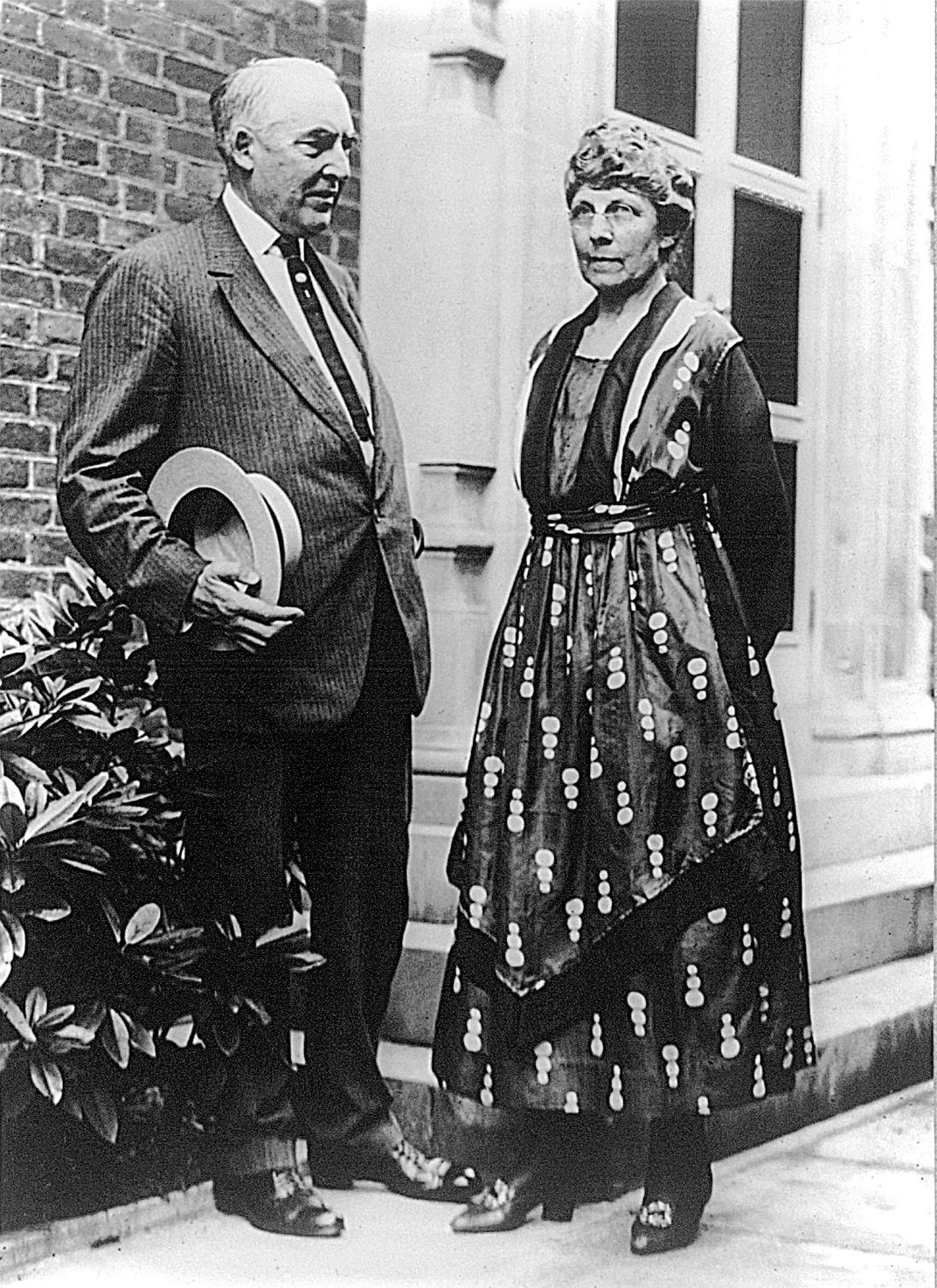

As his administration became increasingly tarnished, Harding fell ill and ultimately died of a heart attack; rumours persisted for years that he had been poisoned by his wife, Florence, though there is no strong evidence.

His reputation has also suffered from his lurid personal life, particularly his two adulterous affairs. One of them, his well-known relationship with Nan Britton, yielded an illegitimate child. The fallout from that relationship has lasted generations, with his grandson fighting to have his body exhumed for DNA testing – a request that was denied by an Ohio judge at the end of 2020.

At the point of Harding’s inauguration, many in the US and in Washington were ready to turn away from the outside world under the banner of “isolationism”. A mentality that took hold after the First World War and persisted under Harding’s administration, it has more than a few echoes in the Trump era.

As it waited impatiently for European countries to pay back the debt and reparations it was owed, the US imposed hardline controls on immigration, partly out of pure racism and partly out of concern that immigrants were out-competing US citizens for jobs. (The two ideas overlapped more than a little.)

Foreign imports were subject to aggressive tariffs in an attempt to protect domestic manufacturers and workers – though the net effect was to crank up the cost of living, raising prices of goods manufactured in the US at greater expense. Foreign trading partners raised their own tariffs in response, making it harder for US producers who dominated the domestic market to sell their goods overseas.

It’s not hard to find the parallels. For European war debts, substitute Nato defence spending requirements; on immigration there are Trump’s travel bans, family separations and the border wall, and on trade, his battles with China.

But the mentality that shaped this agenda in 1921 was very different to the one at work in 2017, when Trump gave his own inaugural speech.

Read today, Harding’s isolationist address seems almost gentle. “Confident of our ability to work out our own destiny,” he said, “and jealously guarding our right to do so, we seek no part in directing the destinies of the Old World. We do not mean to be entangled. We will accept no responsibility except as our own conscience and judgment, in each instance, may determine.

“America, our America, the America builded on the foundation laid by the inspired fathers, can be a party to no permanent military alliance. It can enter into no political commitments, nor assume any economic obligations which will subject our decisions to any other than our own authority.”

Trump’s address was something altogether different. Written at least in part by far-right sympathiser advisers Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon, the speech was a broadside against the arrogant and corrupt Washington “swamp” Trump had campaigned against for 18 months, but it was also a clarion call for a nationalism that bordered on old-style isolationism.

“For many decades, we’ve enriched foreign industry at the expense of American industry, subsidised the armies of other countries while allowing for the very sad depletion of our military.

“We’ve defended other nation’s borders while refusing to defend our own, and spent trillions of dollars overseas while America’s infrastructure has fallen into disrepair and decay. We’ve made other countries rich while the wealth, strength and confidence of our country has disappeared over the horizon.

“One by one, the factories shuttered and left our shores, with not even a thought about the millions upon millions of American workers left behind. The wealth of our middle class has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed across the entire world.”

Like some of the more strident of his predecessors a century earlier, Trump drew the line: “From this moment on, it’s going to be America First.”

Now, the sun has set on Trump exactly 100 years after Harding’s brief reign began. And for all the superficial similarities, the tone he set in 2017 has turned ever darker since – far beyond any comparison with the last century’s “worst-ever” chief executive.

The turn of the 1920s was a time of extreme racist brutality. A rash of lynchings and pogroms had killed scores of black Americans in many cities over the preceding two years, including some of the 20th century’s worst American atrocities during the so-called “red summer” of 1919.

The year of Harding’s inauguration, the Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma saw mobs of white residents attack and incinerate the black neighbourhood of Greenwood, killing scores of people and driving thousands from their homes.

Later that year in Birmingham, Alabama, Harding spoke to a vast crowd of black and white Alabamans segregated from each other by a fence. By 21st century standards, the speech he delivered was plainly racist in various ways – but reading his words today, it is stunning to see a president call on a southern crowd to rethink the racial caste structure it so brutally enforced.

“The idea of our oneness as Americans,” he told the crowd, “has risen superior to every appeal to mere class and group. And so I would wish it might be in this matter of our national problem of races.

“I want to see the time come when black men will regard themselves as full participants in the benefits and duties of American citizenship; when they will vote for Democratic candidates, if they prefer the Democratic policy on tariff or taxation, or foreign relations, or what-not; and when they will vote the Republican ticket only for like reasons.

“We can not go on, as we have gone for more than a half century, with one great section of our population, numbering as many people as the entire population of some significant countries of Europe, set off from real contribution to solving our national issues, because of a division on race lines.”

Trump’s America may not regularly see whites assemble in their thousands to lynch black men based on slander and then sell postcards of the event for posterity, but it has seen increasingly confident rallies by far-right insurrectionists and white supremacists – some of whom Trump has referred to as “very fine people” even in the aftermath of murderous violence.

When last year threw up the most intense mass protest in decades after a run of incidents in which Black people were killed by the police in the cruellest of circumstances – Breonna Taylor, shot dead in her bed by officers executing a raid, or George Floyd, crushed beneath an officer’s knee in the street – Trump was at first silent, then insistent upon “law and order”, playing to the oldest racial clichés about dangerous blacks as he pandered to a furious base.

And on his way out, Trump has now helped incite a mob of enraged supporters to descend on the US Capitol to halt the constitutional transfer of power. One of them carried a giant Confederate flag.

After the disorder and danger wrought by Trump in just his final weeks, never mind the preceding four years, many are updating their worst-presidents-ever lists with him at the top. Yes, Harding was an adulterer who did little to stop his appointees grasping hold of what was not theirs to take. But so was Trump – and for four full years at that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks