Trump is trying to undo the 14th amendment. Historians are horrified.

Black activists championed the idea of birthright citizenship long before it was introduced to the U.S. Constitution, reports Katie Hawkinson

One hundred and fifty-seven years ago, the United States adopted a Constitutional amendment guaranteeing citizenship to people born on U.S. soil, one of the American bedrocks of equality.

Now, that guarantee is under attack.

President Donald Trump issued an executive order Monday night — just hours into his presidency — seeking to end birthright citizenship in the U.S. People across the country were quick to react: more than 20 states and pregnant women sued the Trump administration, a federal judge in Seattle temporarily blocked the order and activists across the country mobilized in an effort to combat the order.

“What we are seeing now is a challenge to one of the foundational pillars of equality and democracy in the United States,” Dr. Martha Jones, an American history professor at Johns Hopkins University, told The Independent. “In a country in which, over nearly all of our history law and politics have been corrupted by racism and xenophobia, birthright has been the great equalizer.”

Here’s what you need to know about how the amendment came to be and how Trump is arguing for it to end:

The 14th Amendment was born from Black activism

Following the Civil War, Congress passed three Constitutional amendments designed to promote racial justice.

One abolished slavery. One allowed Black men to vote. And another, the 14th Amendment written by Ohio Congressman John Bingham, established birthright citizenship and was ratified in 1868.

But Bingham was nowhere near the first to pitch the idea.

Black Americans championed the concept for decades before the amendment, according to Jones, who wrote the 2018 book Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America.

Black Americans, before and after the Civil War, turned to the concept of birthright citizenship “to make the case for their permanent and inalienable relationship” with the U.S., Jones said.

Their idea, Jones said, came from a phrase in the original 1787 Constitution, which states the president must be a “natural born Citizen.” If the president could be a natural-born citizen, Black activists argued, then natural-born citizenship must exist — and why couldn’t the idea extend to them?

“The [amendment] is the culmination, the actualization, of a position that Black Americans had advocated for over the course of many, many decades before the Civil War,” Jones told The Independent.

Birthright citizenship would go on to be upheld by judges for over a century, beginning with the 1898 Supreme Court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark.

But that could all change.

How is Trump arguing for an end to birthright citizenship?

Despite more than a century-long history of judges upholding its place in the Constitution, Trump is attempting to argue for the end of birthright citizenship by claiming it was never supposed to work how it has.

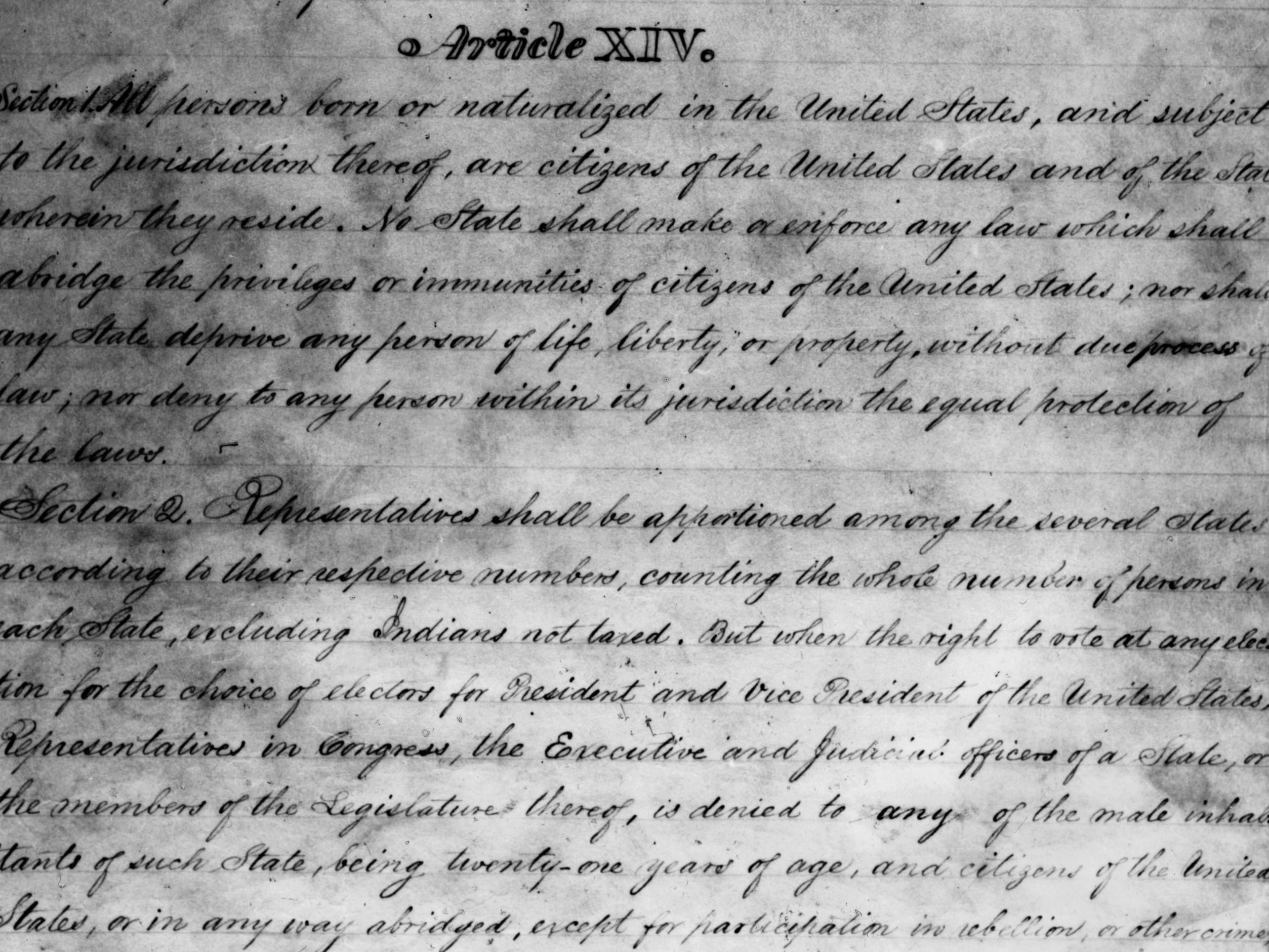

First, look at the amendment’s text: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Trump used the “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” clause to make his case.

In the executive order, Trump argues that people born in the U.S. to many types of non-citizen parents are “not ‘subject to the jurisdiction thereof,’” (that is, not subject to American jurisdiction).

Trump interprets this to mean that mothers without legal permission to be in the U.S. and fathers who aren’t citizens or lawful residents cannot give birth to an American citizen on American soil, according to his order. He also applies this to mothers with “lawful but temporary” U.S. residence and fathers without citizenship or lawful residence.

But, precedent has shown the “jurisdiction thereof” exception has, up until now, only been applied to exclude a select few groups — and certainly not the children of migrants, documented or undocumented, according to Jones.

These groups, she said, include the children of diplomats and the children of members of a standing foreign military occupying the U.S.

At the time of the amendment’s ratification, the exception also applied to Native Americans because they were “members of their own sovereign nations,” Jones said. However, this exception no longer applies after Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, granting citizenship to Native Americans.

Trump’s Justice Department cited this long-gone exception for Native Americans in a court filing Wednesday defending his executive order.

The department’s attorneys cited an 1884 Supreme Court ruling that stated Native Americans are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S., and attempted to argue this means people born in the U.S. to non-citizen parents are also not entitled to citizenship.

However, the case cited was decided 40 years before the Indian Citizenship Act.

So, what’s next for the ‘great equalizer’?

The question of whether Trump can successfully end birthright citizenship will almost certainly make it to the Supreme Court. But what the nine Justices will do is less clear.

“I think we are in for a rocky ride right now in terms of that contestation, and we should probably be prepared for it,” Dr. Manisha Sinha, an American history professor at the University of Connecticut, told The Independent.

Dr. David Blight, an American history professor at Yale University and the author of several books on nineteenth-century America, tells The Independent he hopes the courts rule to maintain birthright citizenship.

“It’s clearly unconstitutional what Trump is trying to do with an executive order,” Blight said. “But it’s much worse than that: It’s trying to turn our history back more than 150 years to a time when those with government power could pick and choose who would be an American.”

Trump’s order has wider implications for the state of racial justice, too — which the 14th Amendment was designed to protect and promote.

“In terms of racial equality and racial justice in the United States, the near future looks extremely dark,” Sinha said.

“But even when it looks pretty grim: I study the abolitionists who were persecuted for their beliefs for a very long time, and who did not enjoy any of the protections of the Bill of Rights for voicing their opinions in terms of fighting against slavery and for Black equality,” she added. “So I would say: Let’s not think that the game is over.”

The Independent has contacted the White House for comment.

Jones called on Americans to look at Trump’s order critically — and to think about how they gained citizenship themselves.

“Americans — or anyone else tuning in — should ask themselves: Why do they think they’re U.S. citizens? They’re U.S. citizens because of the 14th Amendment and because of birthright,” she said.

“This is a status that is conferred to all of us on birth.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks