'Pivotal time:' Museum obtains key 1854 Lincoln letter

Officials at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield have acquired an 1854 letter marking a key transition for the prairie lawyer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

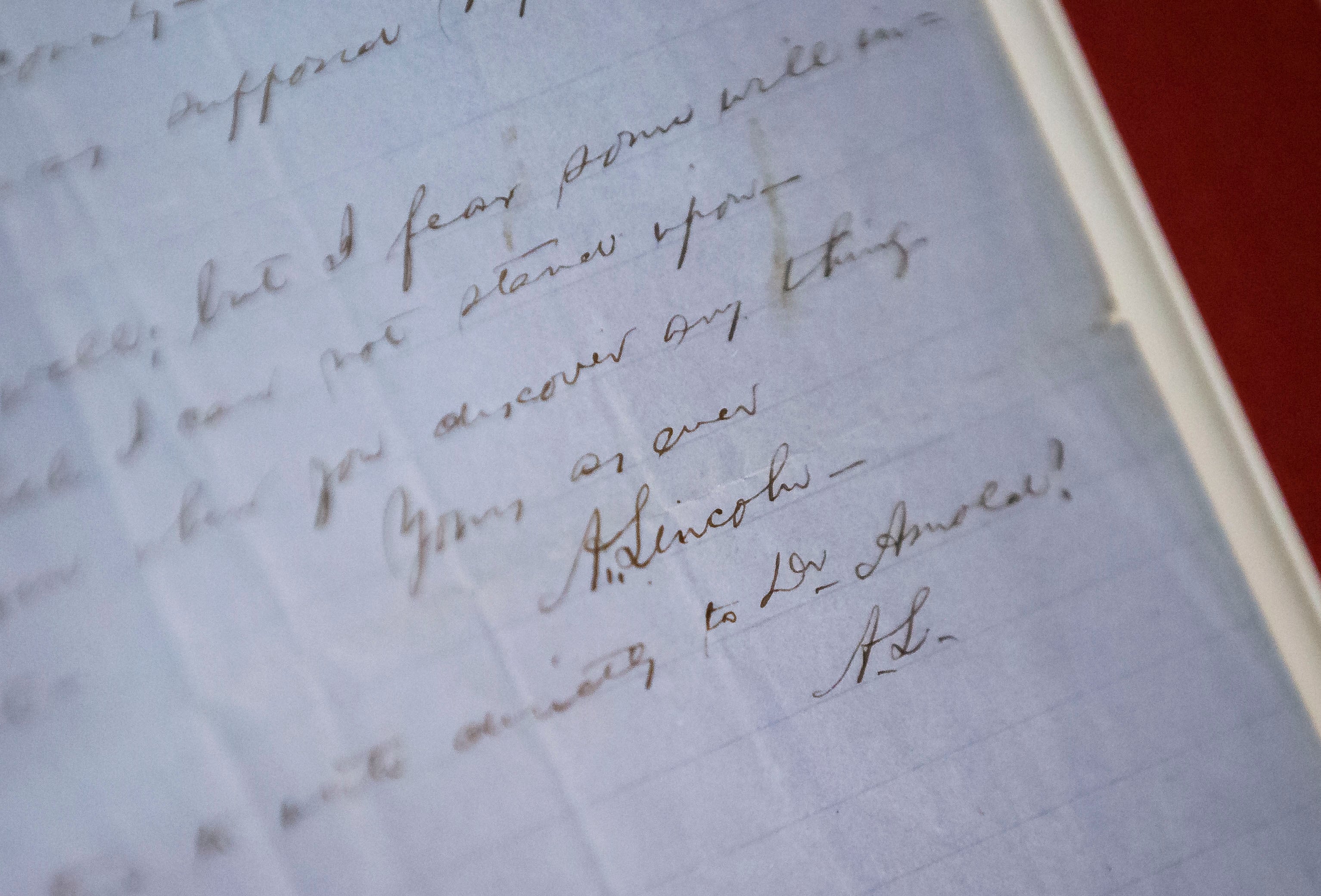

Your support makes all the difference.An 1854 letter hinting at Abraham Lincoln s transition from prairie legislator to political powerhouse, donated to the state of Illinois, was unveiled Thursday at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

The short missive, which a scholar once labeled “in a sense, the most interesting document Lincoln ever wrote,” explains his decision not to return to the Illinois House of Representatives so that he could remain viable for the U.S. Senate. The choice opened the door to the White House and Lincoln's preservation of the nation during the Civil War.

“Lincoln wrote it at a pivotal time in his life. Would he focus on the law or make a return to politics?" Lincoln library and museum executive director Christina Shutt said. "His decision changed history, so it’s appropriate for this letter to find a home at the library and museum dedicated to telling the story of Lincoln’s impact on the world.”

On Nov. 27, 1854, the circuit-riding attorney wrote friend and Peoria attorney Elihu N. Powell: “Acting on your advice, and my own judgment, I have declined accepting the office of Representative of this county.” He was responding to Powell s earlier reminder that service in the state House would prohibit an 1855 Senate run.

Capitol Hill was where Lincoln knew he needed to be to oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the 1854 brainchild of Illinois Sen. Stephen A. Douglas allowing residents of newly established territories to decide whether to allow slavery. It included would-be northern states, thus turning on its head the key theme of three decades of compromise on the issue between North and South. Lincoln at the time was not an abolitionist but virulently opposed expansion of slavery.

Lincoln withdrew from the 1855 campaign but his legendary, if failed, 1858 battle to replace Democrat Douglas catapulted the lanky lawyer into the national spotlight and the White House two years later.

The letter also broaches his inevitable departure from the Whig Party, whose unsettled stance on slavery accelerated its demise. Nonetheless, he fretted over the Anti-Nebraska movement's radical stance on the issue, writing, “I fear some will insist on a platform, which I can not stand upon.”

Fittingly, the letter was donated by Guy Fraker, a lawyer and Lincoln collector from Bloomington, 135 miles (217 kilometers) south of Chicago. It was in Bloomington that Lincoln debuted his Republican leanings at the party's 1856 convention, where he delivered his “Lost Speech,” so called, some say, because reporters were so enthralled they failed to transcribe it. Others say friendly journalists thought better than to publish the fiery anti-slavery rhetoric of Lincoln who by then had emboldened his position.

“Those of us who have been lucky enough to serve as caretakers for Lincoln letters and artifacts have an obligation to ensure they will be shared with the public for generations to come,” said Fraker, author of “Lincoln's Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit.”

An office in Bloomington's courthouse square is also where Carl Sandburg, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Lincoln biography, says Jesse Fell, who founded Bloomington's twin city of Normal and Illinois State University, suggested Lincoln reach for the brass ring in 1860.

The letter’s depiction of Lincoln’s metamorphosis prompted the “most interesting document” characterization by Paul Angle, a Lincoln scholar and historian of the Illinois State Historical Library from 1932 to 1945.

Lincoln served in the Illinois House from 1834 to 1842. In 1846 he was elected to serve one unremarkable term in Congress. He returned to his adopted town of Springfield and a lucrative law career. As a favor to an ally, he ran for and won an Illinois House seat in 1854 before deciding his future was elsewhere.

The letter will be displayed in the museum's Treasures Gallery for one month beginning July 7, replacing the current exhibit featuring the Emancipation Proclamation.

___

Follow Political Writer John O’Connor at https://twitter.com/apoconnor