New faces enter fray as California recall slowly takes shape

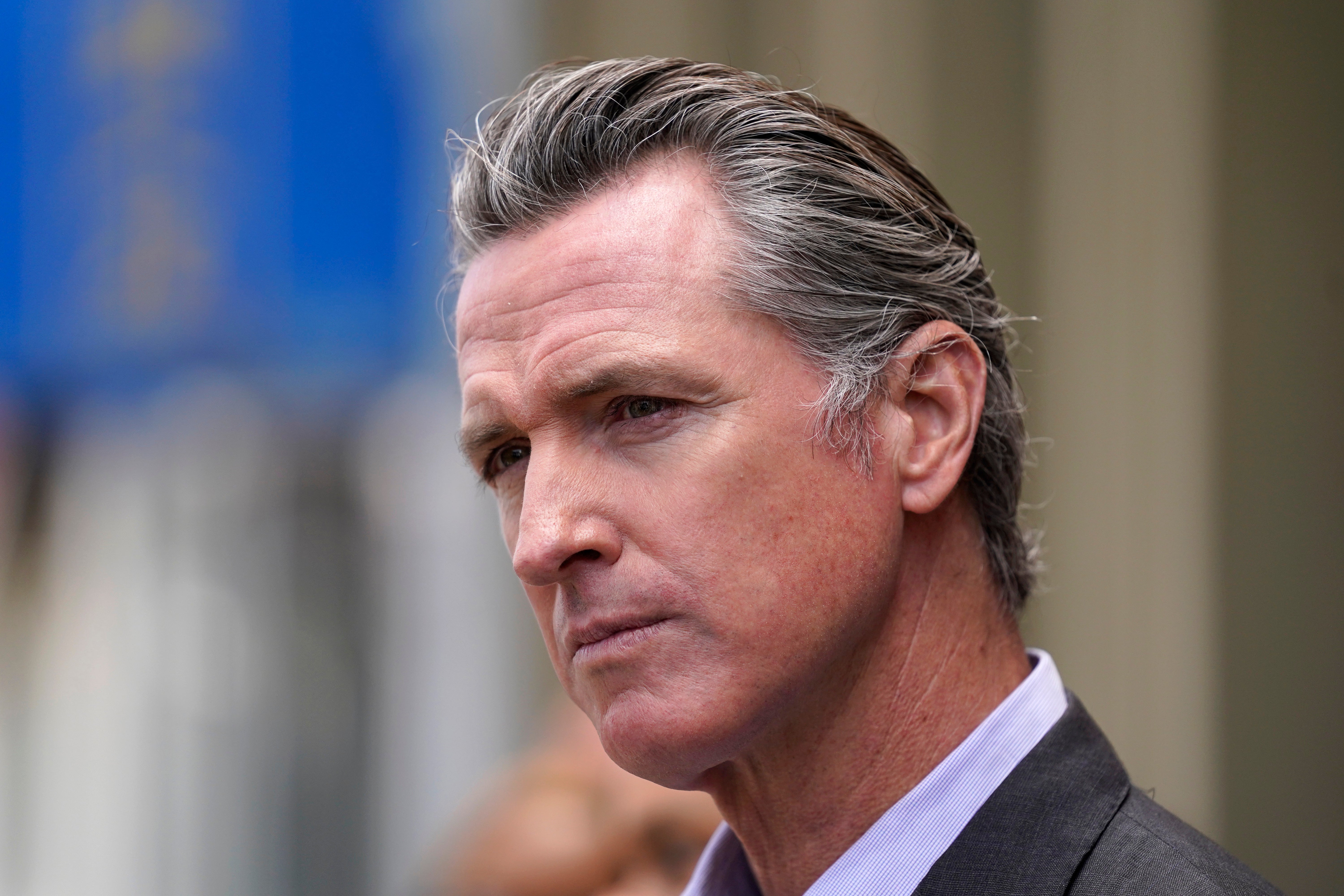

California officials announced six weeks ago that Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom would face an almost certain recall election

Six weeks after California officials announced that Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom would face an almost certain recall election that could drive him from office, the contest continues to be roiled by uncertainty and questions – even the date when it might take place remains unclear.

The list of Republican challengers who have signaled an intention to enter the race is about to top 20, though no consensus front-runner has emerged. State Assemblyman Kevin Kiley this week became the latest to announce he is considering stepping in.

Newsom, meanwhile, has regained his footing after seeing his popularity fall at the start of the year amid the worst of the pandemic and criticism over his COVID restrictions for the public and businesses. The first-term governor has since benefited from a sharp decline in cases during the spring and a record-breaking surplus that allows him to bestow billions on favored projects and issues.

Still, just last week he faced another round of criticism for saying he planned to keep an emergency declaration in place even after the state fully reopens its economy next Tuesday. “There’s uncertainty in the future,” he warned.

The declaration means California can be reimbursed from the federal government for many of its pandemic-related expenses. But it also gives Newsom the authority to suspend state laws and impose new rules. Since declaring this emergency, Newsom has issued at least 58 executive orders to alter or suspend hundreds of laws because of the virus.

Recent polling suggests Newsom would beat back the recall; a Republican hasn't won a statewide race in heavily Democratic California since 2006. But those same surveys reveal signs of an unsettled public: independent voters, for example, tend to view his job performance skeptically and most say the state is going in the wrong direction.

Meanwhile, many voters say they are not paying much attention to the unfolding race, leaving open questions about which way they might turn. The slow push to reopen public schools, an emerging drought that is drying up reservoirs and streams, and the looming wildfire season all pose risks for the incumbent, who was elected in a 2018 landslide.

With Kiley’s potential entry into the race, it signals that many Republicans remain underwhelmed with the field so far, which includes businessman John Cox who Newsom defeated in 2018, former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer and reality TV personality and 1976 Olympic decathlon champion Caitlyn Jenner.

Kiley, who is 36 and represents suburbs east of Sacramento, has been one of Newsom’s chief critics in the state capital during the pandemic. Though little known to a broad swath of voters, he is a hero of sorts among the recall’s most fervent organizers and volunteers.

He sued to stop Newsom’s use of broad emergency powers during the pandemic. A state Superior Court ruled in favor of Kiley, but an appeals court overturned that ruling in May. Kiley and fellow Republican Assemblyman James Gallagher plan to appeal to the state Supreme Court.

Earlier this year he released a book called “Recall Newsom: The Case Against America’s Most Corrupt Governor,” and he spoke at dozens of recall rallies and events during the signature-gathering process.

The recall's chief organizer, Orrin Heatlie, is informally advising Kiley as he ponders a candidacy and said he’s hearing a lot of frustration about the current field, but declined to give specifics.

Heatlie said his assistance to Kiley is being done outside of his role with the recall committee, which is barred from coordinating with a candidate. Heatlie said he reached out to Kiley after getting a slew of phone calls from recall volunteers asking if the assemblyman planned to run.

“With the lawsuit that he had against the governor, he’s gained a lot of notoriety and he’s gotten a lot of attention," said Heatlie, a former sheriff’s sergeant who filed the recall petition and led the volunteer signature-collection drive.

Kiley said he has no timeline for deciding when to run and declined to criticize any of the Republican candidates, saying they all share the goal of getting a majority of Californians to support recalling Newsom.

He said he sees opportunity to appeal to many voters by pointing out California’s failures in dealing with the homeless crisis and poverty, high taxes and that under Newsom public school classrooms remained closed through most of the pandemic — all familiar themes for the leading GOP candidates.

Part of the unsettled landscape around the expected election is the result of the state’s time-consuming rules for placing a recall on the ballot.

State officials announced in late April that recall organizers had gathered more than the necessary 1.6 million petition signatures to place the election on the ballot, following a preliminary count. That kicked off a lengthy review process.

Even now, it’s possible it could take another two months before the recall is certified for the ballot, following various required state financial reviews. Under that scenario, it would push the election into at least October. But given wiggle room in the law, and the potential for more quickly concluding those reviews, that date could come sooner.

The recall took root last year, driven largely by public dismay with Newsom's long-running virus restrictions that shuttered schools and businesses.

In the election, voters would be presented with two questions: Should Newsom be recalled? Who should replace him?

If voters say yes to the recall, then whoever among the listed candidates gets the most votes becomes the next governor.

Tuesday marked the deadline for voters to withdraw their signatures from the recall petition, a new addition to the process adopted by Democrats several years ago after a state senator was removed from office. State elections officials will release the official count later, but it is improbable enough signers pulled back to change anything.

For example, in Orange County, the state's third-most populous county, more than 215,000 people signed the petition. Just one person withdrew, Registrar of Voters Neal Kelley said.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks