Did Mike Pence make Indiana’s HIV crisis worse?

- What kind of governor was Mike Pence?

- How did the outbreak begin?

- How did Pence respond?

- What happened next?

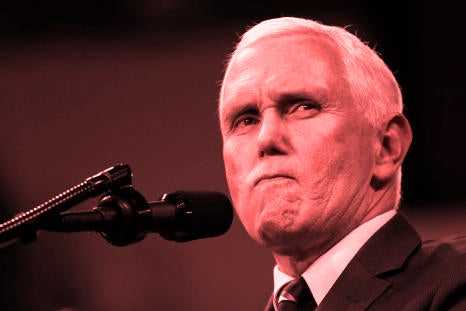

Donald Trump has turned to his vice president, former Indiana governor Mike Pence, to take the lead on handling the coronavirus outbreak as it affects the US.

Pence's appointment has been met with widespread dismay, with many onlookers pointing to his lack of relevant experience, his history of "anti-science" views – and most damning of all, the story of how he handled an HIV outbreak in Indiana while governor.

Pence has long been criticised for the actions he took (or didn't) when the outbreak began, and for his ideological views on public health more broadly. Today, scores of people in his home state are living with HIV. So to what extent is he responsible?

What kind of governor was Mike Pence?

Pence became governor of Indiana in 2013, after 12 years in the US House of Representatives. A staunch religious and social conservative, he oversaw several policies that attracted major controversy, among them the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which was condemned around the world for potentially allowing businesses to discriminate against same-sex couples.

Among his administration’s other policies were several hardline anti-abortion bills and cuts to health services, in particular organisations that offered family planning advice. And top of the list was Planned Parenthood, which he campaigned to “defund” while in Congress.

Pence’s assault on Planned Parenthood was framed as a campaign against abortion, but the organisation provides numerous other services, among them testing for sexually transmitted diseases.

In Pence’s first year as governor, cuts forced the closure of the only Planned Parenthood clinic in Indiana’s Scott County – which would become the epicentre of the outbreak.

How did the outbreak begin?

The Indiana authorities first picked up on the outbreak around the start of 2015, and at the end of February announced “a quickly spreading outbreak of HIV in the southeastern portion of the state” that had seen 26 new cases in just two months. This was a major uptick from the region’s usual HIV infection rate.

The outbreak was centred on Scott County, near the Indiana-Kentucky border, and specifically on the small city of Austin, population around 4,200.

The state found all the new cases were linked to injection drug abuse, specifically the abuse of addictive prescription opioids. In his February 25 statement, the state health commissioner singled out a particular drug: Opana, an opioid painkiller more potent than Oxycontin that many addicted users had started to inject.

At the time, Indiana made it illegal to possess syringes without a prescription with the intent of using them for drugs – and needle exchanges, which would have dispensed clean syringes to users who otherwise shared dirty ones, were forbidden.

The outbreak continued to spread throughout 2015 and into 2016. By the time it was brought under control, the number of infections attributed to the outbreak would reach 215.

How did Pence respond?

Pence was slow to take decisive action to stop the outbreak. He had long opposed the setup of needle exchanges, believing – against abundant evidence – that they did little to tackle drug addiction and perhaps even supported it.

It was only at the end of March 2015, reportedly after two days of prayer, that Pence declared a state of emergency that would allow Scott County to provide needle exchanges. By then, the official number of cases had hit 81.

Announcing the measure, he said: “I’m prepared to make an exception to my long-standing opposition to needle-exchange programmes. This is a public health emergency driven by intravenous drug use.”

However, Pence’s initial order did not authorise exchanges open-endedly, instead only permitting a temporary programme in Scott County alone. It was not until the beginning of May that he signed a law facilitating needle exchanges statewide – provided counties who wanted to start them could prove they were already experiencing outbreaks.

Trump names Mike Pence to lead coronavirus response In May 2016, the state of emergency was extended to continue the needle exchange programme for another year – by which time Pence had left the governor’s office to become Donald Trump’s vice president.

Research conducted since the outbreak has shown that earlier preventative action could have kept the number of infections at a much lower level. A 2018 study in The Lancet found that based on data modelling, a public health health approach to HIV/Aids in the years before the outbreak could have prevented a significant majority of the cases identified.

The incident is now held up as an example of the consequences of paring back or not providing sexual health testing and assistance for drug addicts – as happened in Indiana during the Pence years.

What happened next?

A former director of the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) called the outbreak “the largest drug-fueled HIV outbreak to hit rural America in recent history” and “the largest concentrated outbreak ever documented in the United States”.

While the eventual opening of needle exchanges and launch of other programmes may have helped slow the spread of HIV, the crisis has left scores of people living with HIV in a relatively poor region with limited health services.

What happened in Scott County has happened on a smaller scale other rural and semi-rural areas beyond Indiana. West Virginia’s Cabell County, near the Ohio and Kentucky Borders, saw a spike in HIV cases starting in 2018; by late 2019, the rate of infection had been brought back down. As in southeastern Indiana, injection drug abuse was blamed for the outbreak.

And as the US continues to grapple with the national problem of prescription drug abuse, including by users who inject, a great many areas are still ill-equipped to fend off the threat.

After the Scott County outbreak had declined, the CDC produced a map of counties in the US particularly susceptible to or experiencing HIV outbreaks due to injection drug use. Ten Indiana counties were on the list.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks