Thousands are dying of Covid each week. So why isn’t anyone talking about it in the midterms?

Covid has killed a over million Americans and profoundly changed society, so why isn’t it a major issue this midterm season? Josh Marcus investigates

By the time you finish reading this article, someone in America will have died from Covid, according to CDC data. By Election Day on 8 November, that figure could rise to more than 4,700 people.

If current trends hold, every week, about as many Americans will be killed by Covid as died during the 9/11 attacks. The latter tragedy defined an era of US and global politics, but the rolling crisis of Covid seems to have faded into the background politically this midterm season, thanks to a mixture of lukewarm public health messaging, fatigue among the public and a deeper, baked-in political dysfunction and shallowness in Washington.

It’s a dynamic that leaves those still suffering from Covid, or those most at risk of catching it, feeling like they have to fend for themselves. People are still dying, and matters of great importance are still being decided about coronavirus, yet if you looked at the headlines, you would scarcely know it.

For people like Aliza Pressman, 44, a mother of two in Seattle who’s been struggling with long Covid since March of 2020, the silence is heartbreaking after what she and millions of others have gone through.

She’s had to spend months at a time bedridden, and has had to forfeit quality time with her children, who she says are sometimes afraid to watch their mother in visible pain and exhaustion. She’s struggled with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her spent if she moves too much, bends over, or does too much mental exertion. Once people have already had Covid, the acute and long-term risks associated with a reinfection get even worse, so getting sick again is not an option for her.

“There are so many people who are vulnerable and are just kind of being forgotten about,” she told The Independent. “It does hurt. I have definitely cried about it. I’m just staying focused on literally staying alive. I spent a lot of time and money figuring out how we can survive this winter.”

And she feels that both the Trump and Biden administrations and their supporters have let her down, choosing the political gains of an aggressive reopening mindset instead of an approach grounded in equity and community safety.

“I truly believe that if I followed the CDC advice, I don’t know if I would be alive today,” she said, pointing to guidelines like the agency’s recommendation in in mid-2021 saying most vaccinated people don’t need to wear masks. “If I were, I would be in much worse shape.”

The disappearance from the public consciousness has been profound.

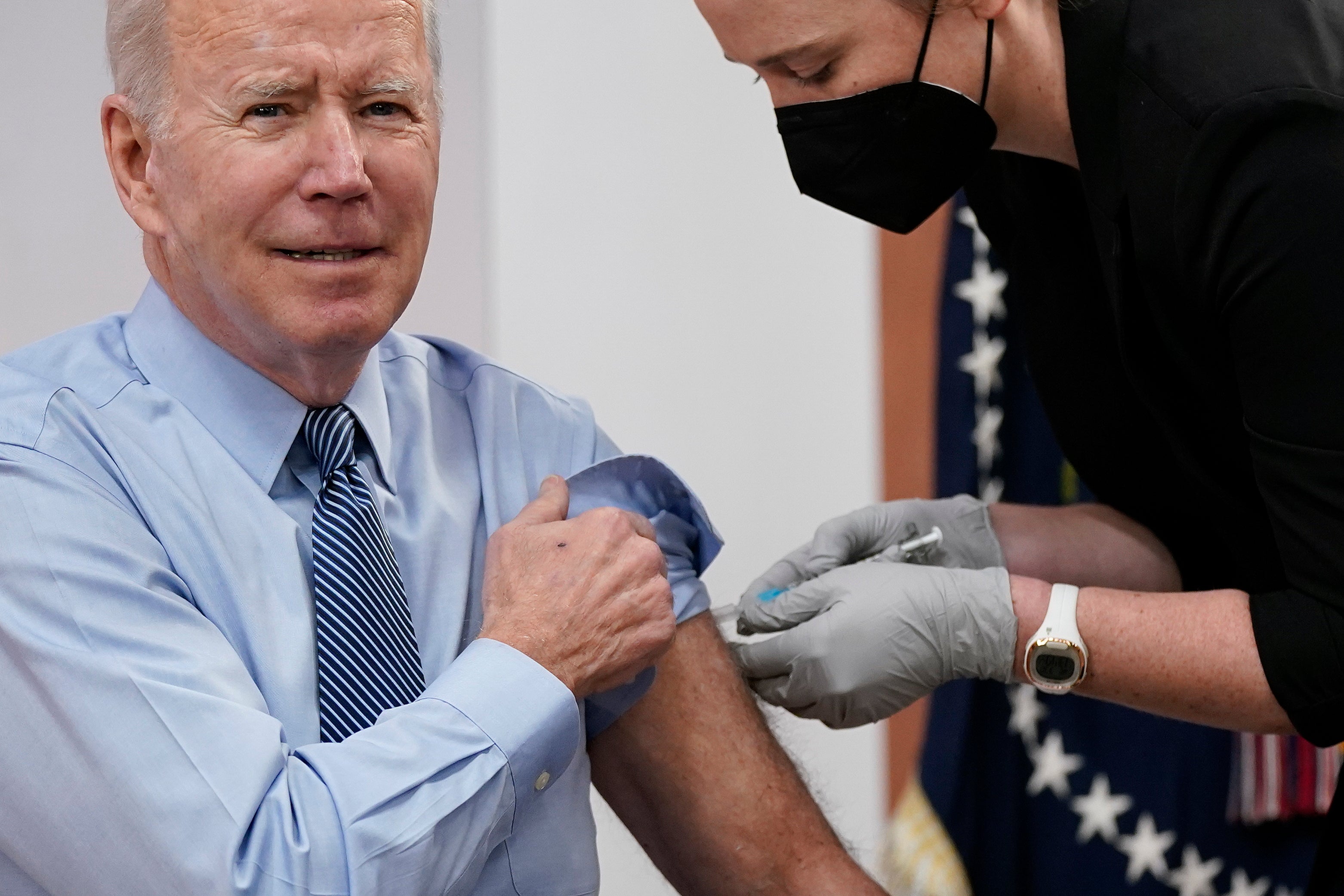

According to recent polling from Monmouth University, voters don’t even rank Covid among their top 10 issues this election. Instead, inflation, crime, and election integrity tended to top the list, with 70 per cent of voters listing those matters as very or extremely important, more than twice the number who said so about the pandemic. Barely a third of Americans aged 18 to 64 have their booster shot.

During the 2020 election, at least on the Democratic side, some form of public healthcare option like Medicare for All was seen as a litmus test. Now two years later, even as researchers estimate a universal government health programme could’ve saved 212,000 lives and $105bn in pandemic-related healthcare costs, the idea scarcely merits a peep from most candidates.

The mass feeling around Covid may be less urgent, but the decisions at stake in Washington this election and beyond about the pandemic could have massive impacts.

The Biden administration, for instance, is considering ending the Covid public health emergency, a decision which could throw 15m people off of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Congress has yet to guarantee another round of funding for things like free Covid vaccines, and drugmakers have warned a single jab could cost as much as $130, a steep barrier for the millions who lack employer-sponsored health care.

A few high-profile candidates have focused on healthcare, virtually all of them Democrats.

In the Georgia governor’s race, Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams has hammered incumbent Brian Kemp over his refusal to expand Medicaid, in one of just 12 states which hasn’t taken advantage of the Affordable Care Act’s funding for such a move. (Mr Kemp favours a partial expansion of the low-income federal health programme, and has pursued other measures to lower costs and increase health access.)

“What’s so grotesque is we’ve got the money,” she said at a recent event with Oprah Winfrey. “The government has access to the money and won’t accept it because he doesn’t believe that people are entitled to healthcare. I can’t find it in me to be that callous.”

In Michigan, where Covid protocols helped inspire a kidnapping plot that threatened her life, governor Gretchen Whitmer has defended her pandemic record, while also making a point in her first TV ad to mention she “made it a priority to get kids back in class.”

“We make tough decisions because lives are on the line,” Ms Whitmer said during a debate this month. “Studies have shown that our actions have saved thousands of lives.”

Her opponent, the Trump-backed Tudor Dixon, has blamed the governor’s policies for killing her elderly grandmother, whose “spirit was crushed” by rules preventing visitation at nursing homes.

“She destroyed our small business community, stole years of schooling from our kids and forced hard-working Michiganders to follow her intrusive orders that picked winners and losers,” Ms Dixon, a Republican, recently told Bridge Michigan.

Even one of the most liberal candidates running for office, Senate hopeful John Fetterman of Pennsylvania, who backs universal healthcare, makes no mention of the pandemic at all on his campaign website.

The Senate race there has focused less on the pandemic as an issue to solve, and more on one as fuel to roast Mr Fetterman’s opponent, celebrity TV doctor Mehmet Oz, who has been criticised for supporting hydroxychloroquine as a Covid treatment, while owning stock in a supplier of the drug.

There’s even a group called Real Doctors Against Oz campaigning against him.

“I was in the ICU during the worst of the Covid pandemic, I saw the death. I heard the cries of despair. I consoled families who were begging me to save their family members. And it makes it so much harder to treat patients when you have so-called physicians pushing hydroxychloroquine and it really degrades the patient-physician relationship — that trust,” Philadelphia physician Dr Ezekiel Tayler, a member of the group, said this month.

The GOP, meanwhile, has gone after the Democrat for supporting Covid lockdowns during his time as lieutenant governor.

It’s all in keeping with the race’s general, insult-filled tenor, and neither candidate has released detailed plans to stop the pandemic.

Polling suggests Republicans and Democrats still remain deeply divided about the pandemic, who’s responsible for prolonging it, and whether figures like Dr Anthony Fauci made things better or worse.

This partisan divide on Covid can be seen in high-profile Republican races too, where the pandemic has been framed as a culture war issue, not a public health one.

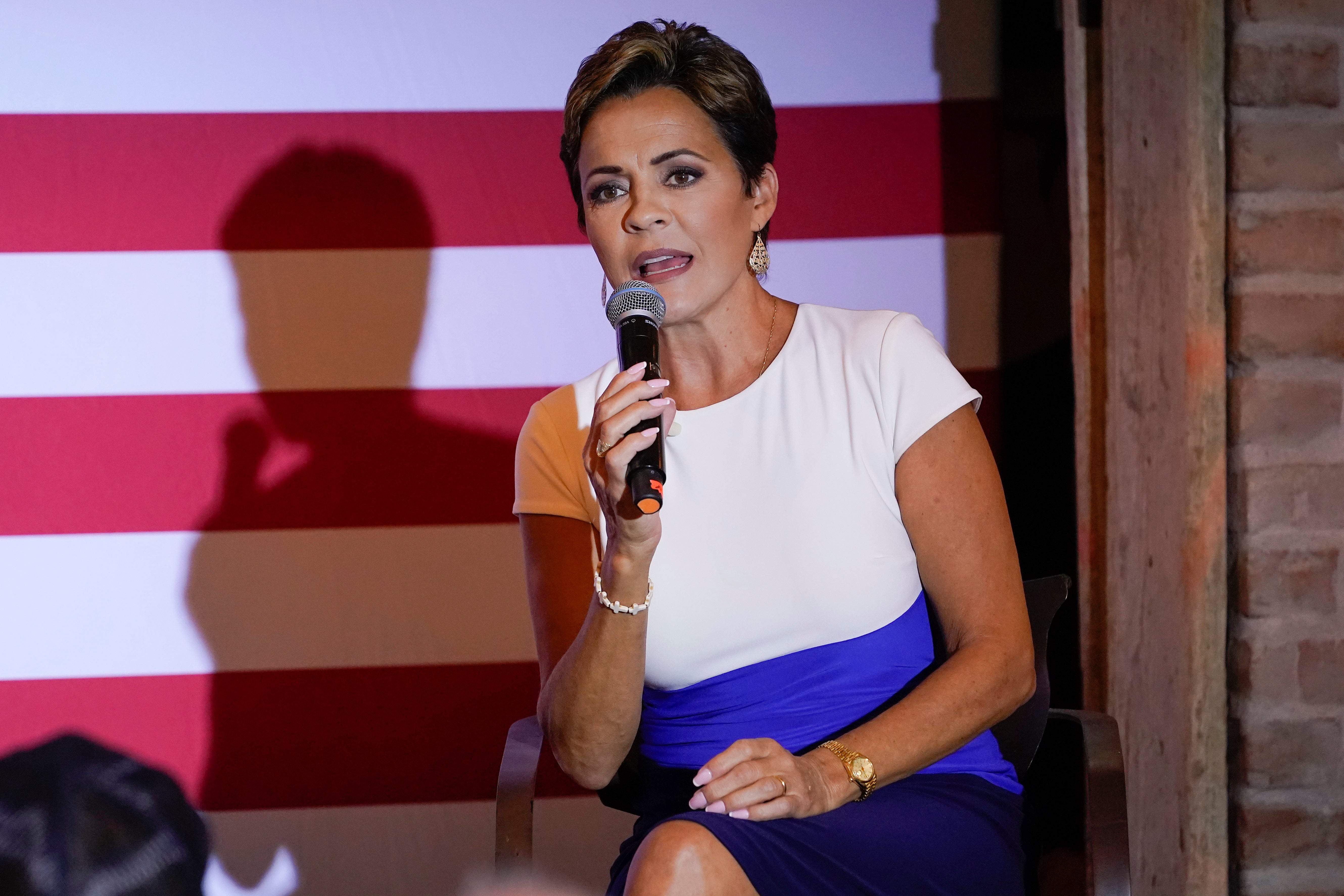

This spring, Arizona gubernatorial candidate (and election denier) Kari Lake proposed an education plan that outlawed masks, vaccine requirements, critical race theory, and sex education before the 5th grade.

In South Dakota, governor Kristi Noem, who is seeking re-election, has campaigned against the “liberal media,” which she claims is against her because her laissez-faire Covid policies were effective. (The state was at one point a global epicentre of pandemic deaths during her tenure.)

“So now they have their sights on me in all kinds of ways. They’re attacking my family, they’re attacking every decision that I make, and they’re trying to tear South Dakota down,” she said in September. “But that isn’t going to happen. Not on my watch.”

She also pledged in October to never mandate Covid vaccines for school children.

In Ohio, GOP Senate candidate JD Vance has previously urged “mass civil disobedience” to push back against vaccine mandates.

"Do not comply with the mandates,” the prominent venture capitalist wrote in a social media post. “Do not pay the government fines. Don’t allow yourself to be bullied & controlled. Only mass civil disobedience will save us from Joe Biden’s naked authoritarianism.”

More quietly, Republicans across the country have also been pushing rules to eliminate or cut down on pandemic-era voting changes like mail-in ballots and drop boxes.

Tracing the source of this pandemic malaise can be difficult.

Is it the Biden administration’s fault, with the president claiming the pandemic is “over”? Is it the fault of Donald Trump and his Republican enablers, who pushed phony Covid cures and undercut public health advice? When was the last time you saw any public official, of any party, in any county, wearing a mask? Are the American people simply fed up with the pandemic, or more worried about their grocery bill and rampant inflation?

Whatever the case, people like Paul Davis, policy director of Right to Health Action, which advocates for global public health investments to fight the pandemic, hopes elected leaders and voters alike remember that the pandemic still isn’t over, and will never truly end unless a deep commitment to health policy is made.

“There is an enormous number of people who can’t move on and who won’t forget,” he said. “They are the millions of healthcare workers who are struggling with PTSD. The 9m people who were left behind by then million-plus people who died, and the tens of million of people who have been disabled by long Covid.”

Ms Pressman argued that many community members respond to government guidelines, and would be willing to continue pandemic measures if they were asked to. The government just needs to have the courage to keep trying, she said.

“Plenty of people here in Seattle would be ok with wearing a mask in drugstores and grocery stores if they were asked to,” she said. “It wasn’t controversial here. There just not being asked to.”

“There’s been this idea that’s kind of been accepted among leaders that the masks are radioactive. I really don’t think that’s actually true,” she added. “It’s kind of like giving up a great tool because someone made fun of you. Democrats let Republicans demonise masks and they just kind of gave up on them and they said we have vaccines.”

She’d love to see whichever Democrats remain in power after the midterms continue solutions like sending free, high-quality N95 masks to Americans, as they did earlier this year, and invest in installing Corsi–Rosenthal boxes in public spaces, low-cost, easy to build, air filtration devices which a growing contingent of scientists and DIY activists are arguing is an essential tool to beating the pandemic.

Others say a key solution is electing more doctors to Congress itself. Right now, there are only 14 doctors in Congress, and most of them are Republicans.

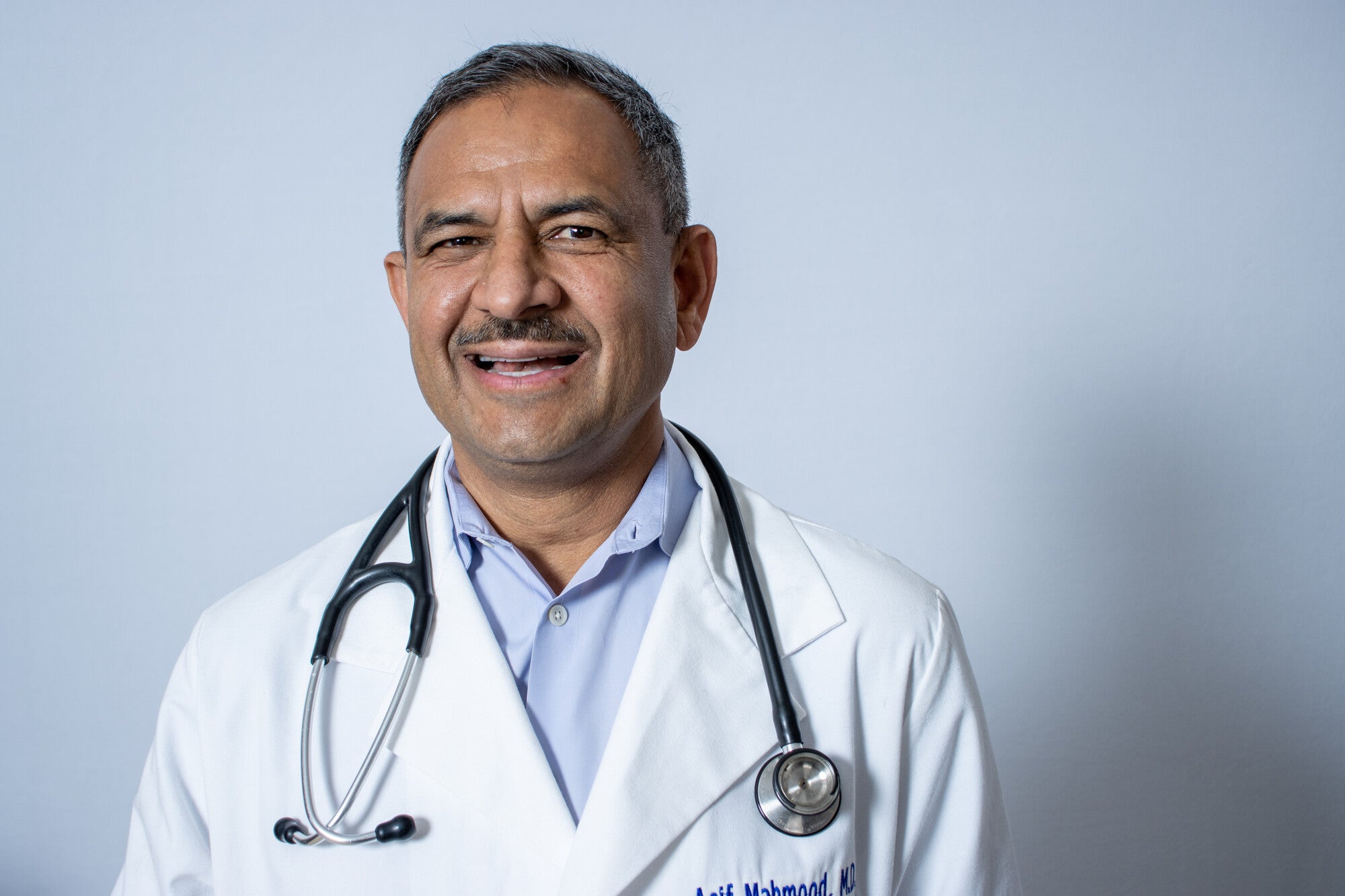

Dr Asif Mahmood, a pulmonologist and Democrat, is running for House in California’s 40th district outside of Los Angeles in the more-conservative Orange County, which is represented by Republican Young Kim.

His central pitch to voters has been that doctors’ no-nonsense focus on helping people while doing no harm is what Washington needs, in a time when a pandemic is raging, when abortion rights are being attacked, and when mass shootings scar communities across the country.

“My whole message is that every single issue which is really at the top level of this election is related to health care, whether it is pandemic or dealing with gun violence, whether it is prescription drug costs, whether it is overhauling our health system, whether it is climate change,” he told The Independent. “A practicing physician can represent and advocate for those rights better than anybody else.”

As a lung doctor, he was on the front lines of the fight against the coronavirus.

“I honestly have seen more people dying in those two years than in my 20 years of practice,” he said. “People of all ages, all races.”

If elected, he hopes to fight for continued federal funding of vaccines, and for better, more clear communications with the public about fighting the pandemic.

Dr Mahmood is one of the candidates backed by Healthcare for Action, a political action committee encouraging more medical professionals to seek office.

The group was founded by Dr Anahita Dua, a leading vascular surgeon from Harvard and Massachusetts General, who said working on the Covid pandemic and seeing mass shootings like the tragedy in Uvalde inspired her to think about making an impact beyond the operating room.

“[Doctors] have got great jobs and good lives and they’ve already got the respect of the community,” she said. “But they’ve had their eyes opened like myself. You can’t just sit in your ivory tower and pretend that everything’s ok.”

Dr Dua believes medical professionals should get into politics because they’re used to making hard choices balancing science, data, ethics, and outcomes, and being able to communicate these decisions to people relying on them in a clear way.

“The problem is that the political world is reacting to Covid almost how Hollywood would react to something. The public is tired of it. Nobody wants to hear it anymore,” she said. “Politics are giving the people what they want, but to their detriment. The job of the government is to take care of people.”

“The politics of our lives deserve more than Twitter soundbites. They deserve thoughtful, critical people who know the issues.”

Mr Davis, of Right to Health Action, says he has seen one encouraging sign this election. His group has organised those directly impacted by Covid to ask candidates on the campaign trail whether they’d support large-scale public investment to prevent future pandemics.

DC politics might’ve poisoned the discussion of Covid, but there seems to be a broader bipartisan agreement that it’s worth stopping the next pandemic. They’ve conducted such demonstrations with about 10 different candidates in swing states, from liberals to die-hard Maga Republicans, and he said they’ve gotten a surprisingly robust agreement.

“It’s horrific that the powers that be have given up on public health protections. They think that people are pandemic tired and maybe there’s some truth to that,” he said. “What we have found is that Covid, while Covid has been politicised by bad actors, like the right wing of the Republican Party, future pandemics have not. Most of the world is actually very willing to talk about preventing future pandemics.”

It’s small comfort to the millions still struggling with our extant pandemic, but a focus on learning from the US’s numerous pandemic mistakes may be the next best thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks