Memphis sanitation workers whose deaths inspired Martin Luther King’s final speech receive minute’s silence

Echol Cole and Robert Walker were crushed by malfunctioning machinery

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Officials in cities across America are honouring the memory of two sanitation workers from Memphis, whose deaths 50 years ago triggered a huge strike and led to Martin Luther King visiting the city where he delivered what would be his final speech.

Mayors and officials from Los Angeles to Philadelphia are holding a minute’s silence in memory of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two black workers who were crushed to death when their rubbish compactor malfunctioned.

Their death was the catalyst for 1,300 fellow sanitation workers to go on strike – demanding safer working conditions for both black and white workers, and improved labour representation.

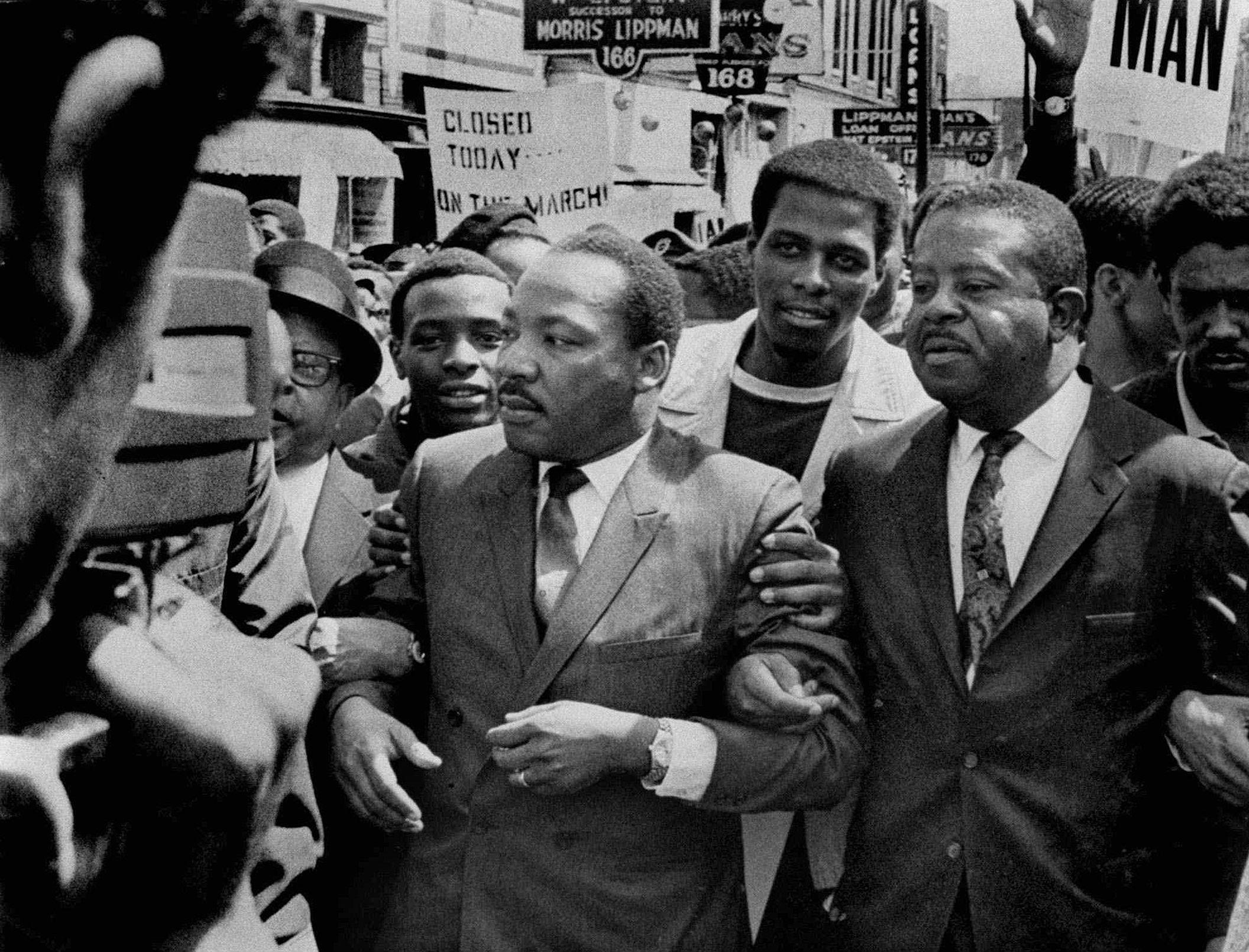

Taking to the streets with banners bearing the words “I Am A Man”, they were joined by King who met the strikers and would later deliver his celebrated “mountaintop” speech at Mason Temple, headquarters of the Church of God in Christ. The following day – 4 April 1968 – the civil rights leader was assassinated at the city’s Lorraine Motel.

“The deaths of the workers became the catalyst,” William Lucy, 84, a union organiser who heard King speak and who is taking part in the commemoration, tells The Independent.

Speaking from Memphis, he adds: “There was a lot of concern with the safety of the equipment and there had been accidents like that before.”

Mr Lucy, a member of the Coalition of Black Trade Unions, says at first the strike was just “low level”. But as it attracted more media coverage, so support grew in other parts of the country.

Although the death of the two black workers on 1 February 1968 happened four years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, which was supposed to put an end to racial segregation, in many places enforced separate facilities for black and white people continued. Even today, in many parts of the country there is de facto segregation in housing and education.

Mr Lucy says conditions for the workers were appalling. They had no toilet facilities and had to make use of a bucket, and there were no bathroom or showers to clean themselves before they went home or before lunch. Frequently, workers could not even afford lunch, he adds.

Another former striker, Elmore Nickleberry, taking part in the memorial says: “The conditions for us were terrible. They treated us like less than men and they called us ‘boys’. I remember not being allowed to take a shower at work and having to come home in order to wash the maggots off my body.”

Rev Cleophus Smith, now aged 75, still works for the city’s sanitation department. He was 24 during the strike. Mr Smith also met King and heard him deliver his final speech on 3 April – during which he concluded by saying he knew the civil rights and labour movements had “difficult days ahead”.

“It really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life; longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now,” King said in his speech.

“I just want to do God’s will. And he’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.

“So I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the lord.”

The following day King was assassinated as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. He stood alongside fellow civil rights campaigners Jesse Jackson and Ralph Abernathy, and musician Ben Branch. The assassin, James Earl Ray, fled and was eventually captured in London.

He pleaded guilty to killing Martin Luther King and was jailed. He died in prison in 1998 at the age of 70. The man he murdered decades before was aged just 39.

The killing of King stunned the nation, shook the civil rights movement and sparked protests and riots in many cities. Mr Smith remembers learning the news on the night of 4 April from people shouting and screaming in the street outside his house, and his wife going outside to find out what the noise was about.

“I remember what was going through my mind – all hope is gone,” he says.

Mr Lucy, who believes King had a sense of “foreboding” when he spoke at Mason Temple, says while conditions for workers have improved in the 50 years since the protests, there is still much to do.

He says many companies and employers are resistant to paying a living wage and even the recent movement to demand $15-an-hour was not sufficient for a family of four.

As to Donald Trump’s appeal to poorer, white voters, he says the President has scapegoated people of colour and told white people it was them who had taken away their jobs. He accuses Mr Trump of racism, and adds: “He gave them encouragement to hate.”

“I don’t believe that everyone who voted for Trump was a racist. But I do believe that every racist who voted, voted for Trump.”

Memphis is among those cities honouring the two workers, whose deaths 50 years ago sparked the strike by members of the union, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. Wreaths are being laid and speeches delivered.

A nationwide moment of silence is being held at 1pm (US time) today as part of I AM 2018 – a movement sponsored by the union and the church where King last spoke, which hopes to continue to press for better conditions for workers. I AM 2018 will hold a series of events ahead of the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments