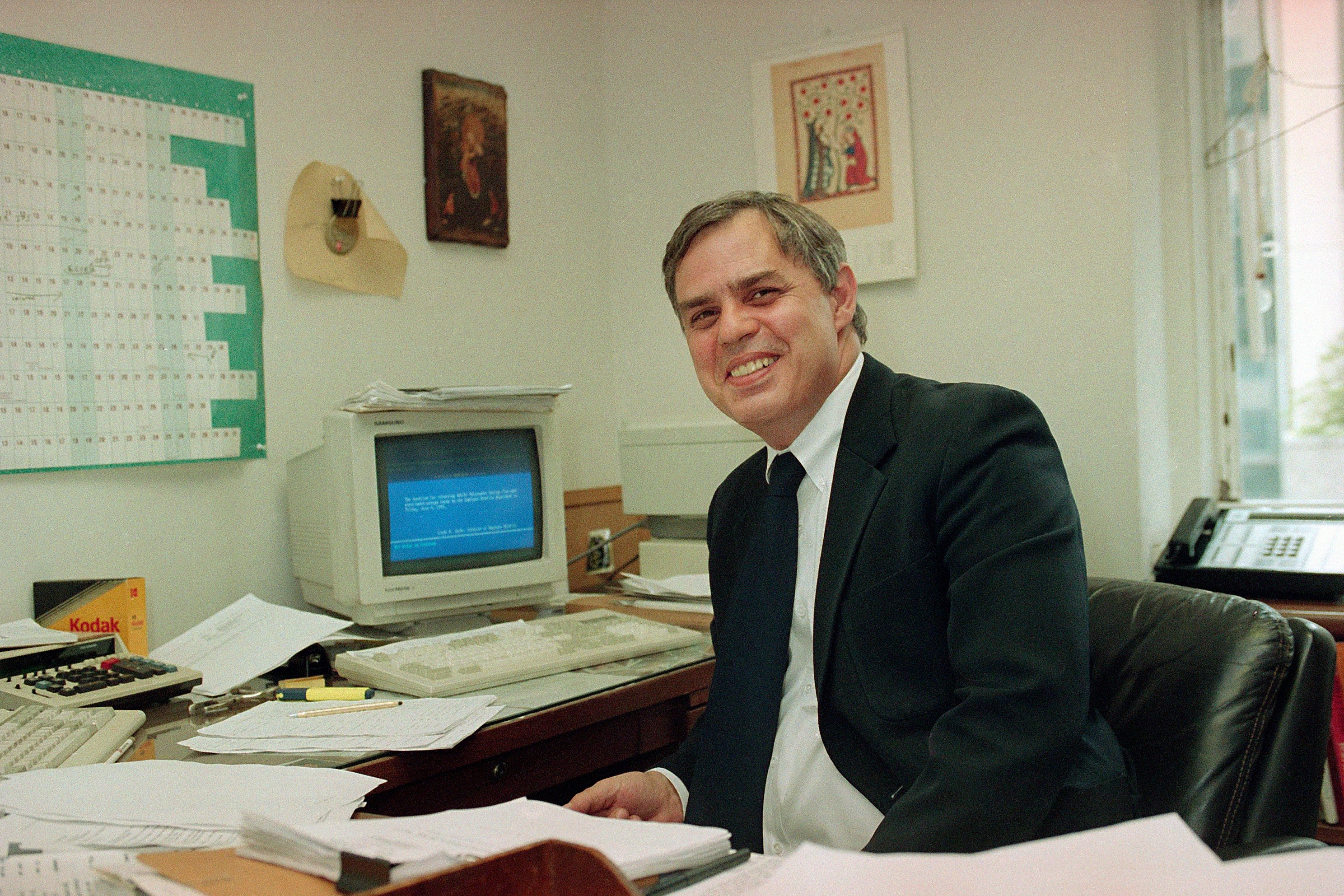

Larry Heinzerling, AP executive and bureau chief, dies at 75

Former AP executive and foreign correspondent Larry Heinzerling has died after a short illness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Larry Heinzerling, a 41-year Associated Press news executive and bureau chief who played a key role in winning freedom for hostage Terry Anderson from his Hezbollah abductors in Lebanon has died after a short illness. He was 75.

Heinzerling, who passed away at home in New York on Wednesday night, served as AP bureau chief in South Africa during a time of popular revolt against apartheid and in West Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall He was deputized by then-AP President and Chief Executive Officer Lou Boccardi to seek contacts with governments and international intermediaries to obtain the release of Anderson, the AP bureau chief in Beirut who had been kidnapped by the extremist group in 1985.

He worked behind the scenes for nearly seven years to win Anderson’s release in 1991.

At AP headquarters in New York, Heinzerling was director of AP World Services and later deputy international editor. He was the son of the late Lynn Heinzerling, a Pulitzer Prize-winning foreign correspondent for the AP in Europe and Africa.

“Larry followed in the footsteps of his illustrious AP correspondent father but he walked his own widely admired path — reporter, editor, bureau chief, headquarters executive and, in one painful period in AP history, my personal envoy as we searched across the world for the key to freedom for Terry Anderson," Boccardi said in an email Thursday.

“Larry epitomized the enduring values of honor, trust, grace under pressure and talent. He was a joy to have in the AP family."

Brian Carovillano, AP vice president and co-managing editor, said: “Larry was a rock of the AP, someone who believed completely in our mission and the power and importance of eyewitness journalism. He also did as much as anyone to help transform this company into the global organization it is today. His impact on AP and its journalism will endure."

Heinzerling grew up partly in Elyria, Ohio, and partly overseas in Johannesburg, Geneva and London among other cities where his father was posted. His father was a World War II correspondent for AP and won his Pulitzer in 1961 for coverage of the 1960 Congo crisis as the country emerged from Belgian colonial rule.

Heinzerling graduated from Ohio Wesleyan College before joining the AP in Columbus in 1967, simultaneously acquiring a master's degree in international journalism at Ohio State.

After a stint at AP's New York international desk, Heinzerling was posted to sub-Saharan Africa, first in 1971 to Lagos, Nigeria, recently torn by civil war as West Africa correspondent, and then to Johannesburg as South African bureau chief in 1974. There he covered the 1976 Soweto uprising and ongoing cycles of violence and repression as the white minority government sought to maintain its racist system of apartheid.

In 1978, Heinzerling was named bureau chief in Frankfurt, West Germany, overseeing AP's newsgathering from central Europe and directing the large AP German service, then the second-largest news agency in Germany. Berlin was a divided city and East-West tensions seethed in Europe and in the country struggling to overcome the legacy of World War II.

His acumen at running a complex news and business operation resulted in his being called back to New York in 1983 to become deputy director and then director of World Services, the department that managed all of AP's non-U.S. businesses and the distribution of news and photos outside of the United States.

When Anderson was kidnapped in March 1985, one of a string of hostage-takings by Iranian-backed Hezbollah militants, Heinzerling became the AP's point man in secret, backdoor diplomacy to find a way to persuade the kidnappers to let Anderson go. In later years, he declined to talk about his efforts, honoring the promises of secrecy he made at that time.

“Larry Heinzerling was an extraordinary man in a great many ways. He was a special person for me both for his efforts on my behalf during my captivity, and the friendship we enjoyed after my return,” Anderson said. “He also happened to be an excellent journalist, and a kind and gentle man. I will miss him, as will we all.”

Ian Phillips, AP’s director of international news, agreed.

‘’Larry was the type of boss you loved to work for,” Phillips said. “He had a contagious laugh that would resonate around the newsroom and elicit smiles even on the toughest of days. He had high standards, but also knew how to bring a sense of fun to the workplace and was held in such high regard by all. He had a global perspective and delighted in sharing stories from when he worked in the field in Africa and Europe.’’

Within the AP, Heinzerling was known for fostering dozens of careers over the decades, and tributes to him poured in from around the world at news of his passing. Longtime AP writer Maureen Johnson in London recalled when he hired her in 1977 in South Africa.

“Larry was clever, a born journalist, a skilled linguist — and much else. He was kind, amusing, courageous and to me, who counted for nothing in the scope of his career, totally supportive. He gave me a crack at the many world class stories which Southern Africa served up at the time: the ending of Rhodesia’s bloody civil war and with it the collapse of white minority rule; the last years of apartheid strung with famous names: the Mandelas, Steve Biko, P.W. de Klerk."

“He remained for me a guiding light," she said.

Retiring from the news cooperative as deputy international editor for world services in 2009, Heinzerling spoke of his career.

“I have had a wonderful career at AP and in no small way it has been my life,” he wrote. “I am thankful for a magical childhood in Europe and Africa as the son of an AP foreign correspondent, and I am even more grateful for the many exciting professional opportunities and adventures AP has offered me over the past 40 years. Where else can you travel the world, report historical events, work with great people every day in a common cause and be proud of what you do?”

Heinzerling is survived by his wife of 20 years, Ann Cooper, the former director of the Committee to Protect Journalists and a retired Columbia Graduate School of Journalism professor.

After retirement, he and Cooper volunteered around the world to build homes for Habitat for Humanity and he taught journalism and mentored students as an adjunct assistant professor at Columbia's journalism school and its school of public and international affairs.

More recently Heinzerling was completing a history of the AP in Germany during and after Hitler's rule: “Newshawks in Berlin: Nazi Germany, The Associated Press, And the Pursuit of News," with an AP colleague, investigative researcher Randy Herschaft. Set mostly in wartime Berlin, the book examines how the AP covered Nazi Germany with news and photos from inside the Third Reich throughout World War II.

Heinzerling's illness emerged suddenly in late June, after the couple finished a cross-country car trip to visit her son and his stepson Artyom (Tom) Keller in California. Heinzerling was diagnosed with cancer shortly after, complicated by an attack of pneumonia last week.

Cooper, Keller, and Heinzerling's two children, Kristen Heinzerling and Benjamín Heinzerling, were with him at his death. Other survivors include their spouses, Thomas Minty and Gabriela Lopez Heinzerling; two more stepchildren, Andreas Klohnen and Eva Klohnen; and five grandchildren. A son, Jesse Heinzerling, passed away earlier.