When are the Iowa caucuses and why are they so important?

Prominent Iowa pollster tells Gustaf Kilander, ‘it should be impossible to poll caucuses accurately because they’re designed for things to change at the very last moment’

The reason why the Iowa caucus matters is the same reason why money has value: Because people believe it does.

Over just a few decades, the Iowa caucuses went from a local affair to a national circus, with some presidential candidates gambling their entire campaigns on their fortunes in the corn-covered Hawkeye State. The next iteration of the is set to take place on 15 January 2024.

‘The entire Iowa caucus game is really about expectations’

Des Moines Register politics reporter Katie Akin has been to countless events in Iowa this campaign season.

“The entire Iowa caucus game is really about expectations,” she tells The Independent. “And that’s true throughout the entire early campaign all the way up until caucus night.”

“It’s the first chance for these candidates to really impress or disappoint the people who are watching this race. And that is all based on how they are expected to do versus how they end up doing,” she adds.

Iowa’s rise in political importance was unplanned — the process used to be dominated by political insiders and there was little opportunity for regular members to have any influence, as The New York Times has noted.

That began to change in 1968, with both the country as a whole, and specifically the Democratic Party, experiencing significant unrest amid the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. The battle between party leaders and rank-and-file members came to a head at the Democratic Convention, where protesters clashed with law enforcement.

The uneasiness stretched onto the convention floor, and the party eventually began to rethink the process for how they choose their presidential candidates to include the voices of regular party members.

New rules in 1972

This led to new rules for the 1972 contest and the four stages in which Iowans now choose their preferred candidates, beginning on the precinct level. The precinct votes are the caucuses where people gather in community centres, sports halls and, in less populated areas, even people’s homes. But there’s also voting taking place on the county, congressional district and state levels.

These new rules, while making the process more accessible and inclusive, also led to further delays as newly formed committees needed updated election materials. However, the state party only had an old machine to make the required copies, leading the state party to decide they needed at least a month between each voting stage to get everything in order in time.

The national convention was set for early July, meaning that the state convention could take place in June, but at the time, the state party was unable to locate a big enough venue, pushing each stage further back, meaning that the process had to begin earlier in the year.

The party chose 24 January as their start date in 1972, making the caucuses the first presidential contest in the nation. While the New Hampshire primaries had been first since the 1950s, Iowa Democrats weren’t in earnest moving their contest earlier to garner national attention, The Times noted. But the national spotlight came to Iowa anyway, beginning with the campaign of South Dakota Senator George McGovern. The longshot candidate was struggling in the polls against the frontrunner, Maine’s Senator Edmund Muskie.

Party expected no interest in caucus results

On caucus night, state party officials convened at the party headquarters, where New York Times reporter Johnny Apple was one of about a dozen members of the press in attendance. He was the only one who asked for the results that night, but the party wasn’t ready to release them, having not expected any interest. A party official, Richard Bender, organised a phone tree to get all the results from around the state.

Apple’s article published the following morning revealed Muskie as the winner but that McGovern had received 22 per cent of the delegates, helping bring the caucuses into the national spotlight. Muskie’s less-than-impressive win went against all expectations. Similarly, McGovern’s strong second-place finish was also a surprise.

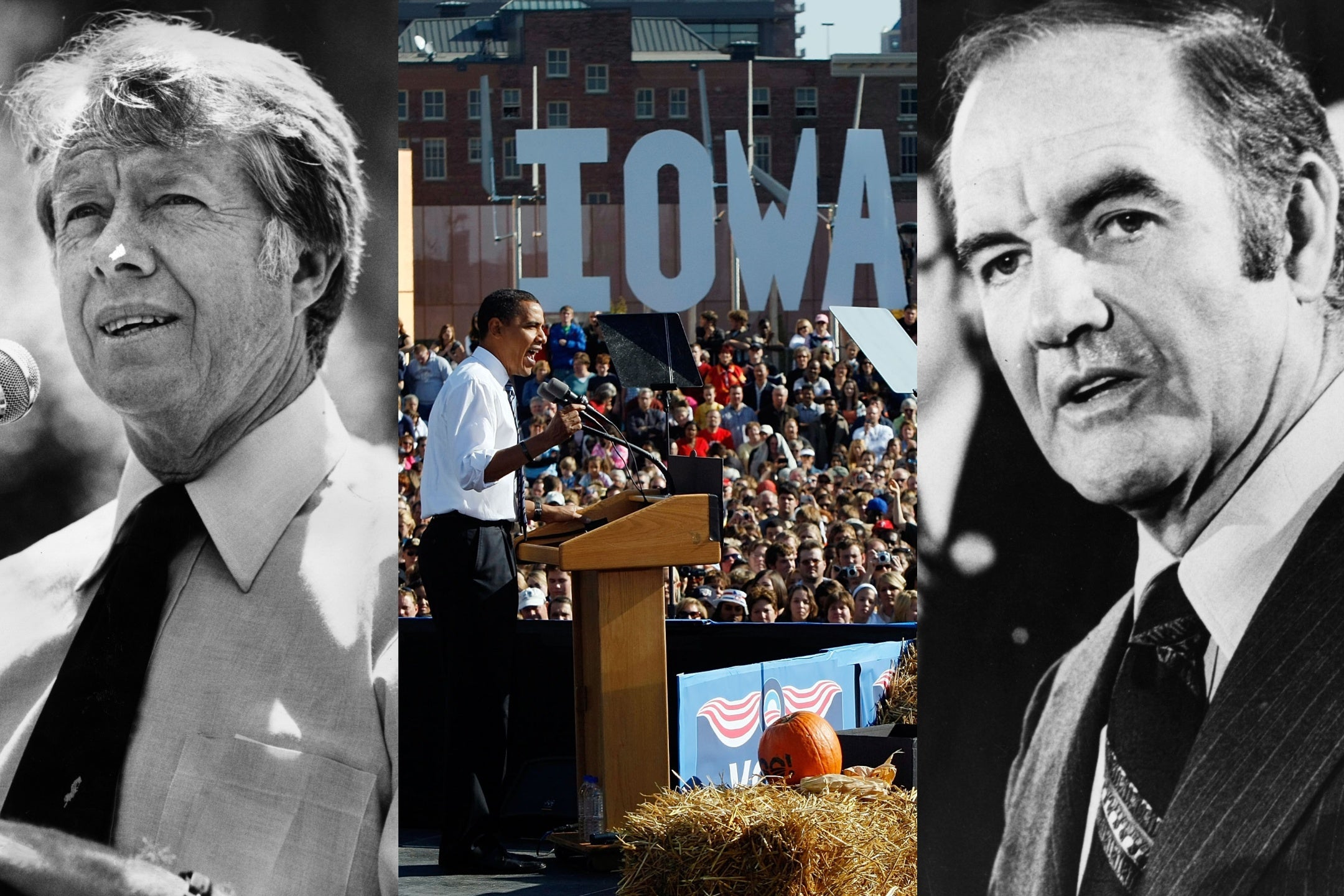

As with the surprising wins of Barack Obama in 2008, Rick Santorum in 2012, John Kerry in 2004, George HW Bush in 1980 and Jimmy Carter in 1976, the strong second-place result for McGovern first showed in 1972 that a lesser-known candidate can come from behind and do better than expected thanks to the new rules first used almost 52 years ago, changing the narrative and building momentum for a nascent campaign.

‘The key in Iowa is you never say never’

“I think the key in Iowa is you never say never,” Ms Akin says. “Looking back at previous cycles, there have been people who saw a surge in support just in the last couple of weeks before the caucus, even in the last couple of days.”

“Iowa is the least predictable,” Ann Selzer, a prominent Iowa pollster, tells The Independent. “We look at the largest number of candidates.”

“Keep in mind that in 2012, [Mr Santorum] had polled only as high as maybe five or six per cent poll after poll after poll. The final poll was the first time he ever hit double digits.

“Our polling showed him on an upward trajectory — that didn’t happen until the final week ahead of the caucuses,” she says. “And by caucus night, he won.”

In 2016, in the Democratic primary Hillary Clinton was “leading, leading, leading”.

“[Vermont Senator] Bernie Sanders never dipped in our polling and he started at three per cent. And by caucus night, he lost by less than one delegate equivalent. It’s just as it is designed, for things to happen late, and for there to be surprises,” she adds.

McGovern went on to win the Democratic nomination in 1972, losing to incumbent Republican President Richard Nixon, who resigned in disgrace just two years later.

Despite his loss, people remembered how McGovern was propelled by the caucuses — one of those people being Mr Carter, the former Georgia governor.

In 1975, ahead of the election next year, Mr Carter began campaigning in Iowa before anyone else in the Democratic race to take on Mr Nixon’s successor, President Gerald Ford.

Mr Carter was an unknown candidate, who initially garnered little press attention, with “Jimmy who?” becoming a catchphrase. Spending much more time in the state than his competitors, Mr Carter won Iowa, and later the Democratic nomination, as well as the presidency.

By 1980, the Republicans had also taken note of the growing importance of Iowa. George HW Bush narrowly beat then-California Governor Ronald Reagan, who was leading going into the caucuses but skipped the last debate ahead of the contest. Mr Bush, who was selected by the eventual nominee, Mr Reagan, to be his running mate and served eight years as his vice president before ascending to the presidency himself, became the third candidate in a row to come from behind and finish strong in Iowa, changing the narrative and building momentum.

Since then, the number of candidates seeking a boost from doing well in Iowa has only increased, partly because of the state embracing their first-in-the-nation status — even if most candidates who win Iowa don’t end up becoming president.

“You never know what’s going to happen in Iowa until it happens,” Ms Selzer says. “I was just looking back at some data from past years — we’ve had people who poll first in November or October … and then they come in third or fourth on caucus night.”

Sky-high expectations for Trump

Speaking about the expectations game in the small state, Ms Akin notes that Mr Trump has been the frontrunner for the entire race, meaning “the expectations for him are very high”.

“If he only wins the Iowa caucus by 15 points, that is a red flag for him,” she adds. “Whereas for another candidate who did not have such sky-high expectations, 15 points would be a fantastic victory.”

“Maybe [Florida Governor Ron] DeSantis will have a huge surge and come in first, that would be wild. But … people like DeSantis, and [ex-UN Ambassador Nikki] Haley are positioned in a place where they might be able to get that strong second-place finish and that might be enough to really create some doubt in the next several primary competitions after Iowa about how strong Trump is as a candidate,” Ms Akin posits.

“It’s all about balancing those expectations … if someone is able to do something surprising, then it could shake things up a lot,” she notes.

“I have been active in enough caucuses — I’ve seen everything happen,” Ms Selzer adds.

The events of caucus night in 2016 show just how unpredictable and fluid the Iowa process is, the pollster notes.

“Our final poll in 2016, had Trump leading, and then he did not win. What I’ve heard from people who attended — Republican caucus-goers — is that the Trump campaign did not really understand what to do on caucus night,” she says.

“They didn’t understand that the caucuses are designed for things to happen in the room on caucus night — there’s a moment in time where a representative from each campaign stands up and makes their pitch — they get a couple of minutes to do it. And often there was nobody from the Trump campaign who was designated to be the one to speak on his behalf,” she adds. “You also had a very smart Ted Cruz campaign [with] operatives spread out around the state who work[ed] the room before the vote gets taken. Apparently, they knew that Dr [Ben] Carson was not going to New Hampshire that night — he was going home to Florida.”

“They said, ‘Look, he’s going to drop out. If you’re voting for him, come join us come, come along, come along’,” she recalls, adding that it was “person-to-person politicking at the last possible moment”.

“If you don’t know how to get the votes, [how to] get your name written on a piece of paper, you can lose that way,” she notes. “I presume that Donald Trump and his campaign learned their lesson from that, so I don’t expect them to be as ill-equipped for what’s going to happen on caucus night. But again, that’s one of the [reasons] it should be impossible to poll caucuses accurately because they’re designed for things to change at the very last moment.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks