G. Gordon Liddy, Watergate mastermind, dead at 90

G

G. Gordon Liddy, a mastermind of the Watergate burglary and a radio talk show host after emerging from prison, died Tuesday at age 90.

His son, Thomas Liddy, confirmed the death but did not reveal the cause, other than to say it was not related to COVID-19.

Liddy, a former FBI agent and Army veteran, was convicted of conspiracy, burglary and illegal wiretapping for his role in the Watergate burglary, which led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon He spent four years and four months in prison, including more than 100 days in solitary confinement.

“I’d do it again for my president,” he said years later.

Liddy was outspoken and controversial, both as a political operative under Nixon and as a radio personality. Liddy recommended assassinating political enemies, bombing a left-leaning think tank and kidnapping war protesters. His White House colleagues ignored such suggestions.

One of his ventures — the break-in at Democratic headquarters at the Watergate building in June 1972 — was approved. The burglary went awry, which led to an investigation, a cover-up and Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

Liddy also was convicted of conspiracy in the September 1971 burglary of defense analyst Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, who leaked the secret history of the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers.

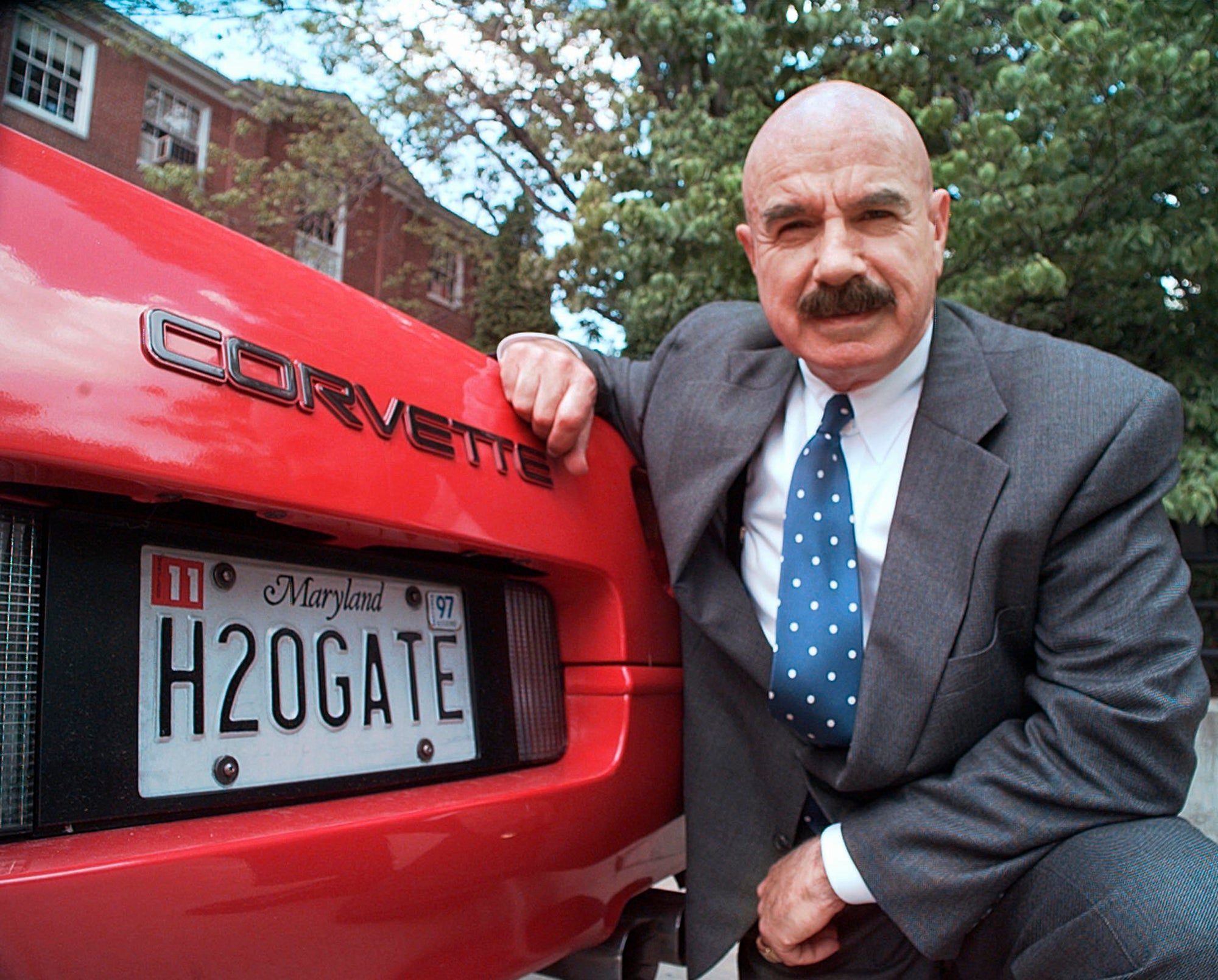

After his release from prison, Liddy — with his piercing dark eyes, bushy moustache and shaved head — became a popular, provocative and controversial radio talk show host. He also worked as a security consultant, writer and actor.

On air, he offered tips on how to kill federal firearms agents, rode around with car tags saying “H20GATE” (Watergate) and scorned people who cooperated with prosecutors.

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, George Gordon Battle Liddy was a frail boy who grew up in a neighborhood populated mostly by German-Americans. From friends and a maid who was a German national, Liddy developed a curiosity about German leader Adolf Hitler and was inspired by listening to Hitler’s radio speeches in the 1930s.

“If an entire nation could be changed, lifted out of weakness to extraordinary strength, so could one person,” Liddy wrote in “Will,” his autobiography.

Liddy decided it was critical to face his fears and overcome them. At age 11, Liddy roasted a rat and ate it to overcome his fear of rats. “From now on, rats could fear me as they feared cats,” he wrote.

After attending Fordham University and serving a stint in the Army, Liddy graduated from the Fordham University Law School and then joined the FBI. He ran unsuccessfully for Congress from New York in 1968 and helped organize Nixon’s presidential campaign in the state.

When Nixon took office, Liddy was named a special assistant to Treasury and served under Treasury Secretary David M. Kennedy. Liddy later moved to the White House, then to Nixon’s reelection campaign, where his official title was general counsel.

Liddy was head of a team of Republican operatives known as “the plumbers,” whose mission was to find leakers of information embarrassing to the Nixon administration. Among Liddy’s specialties were gathering political intelligence and organizing activities to disrupt or discredit Nixon’s Democratic opponents.

While recruiting a woman to help carry out one of his schemes, Liddy tried to convince her that no one could force him to reveal her identity or anything else against his will. To convince her, Liddy held his hand over a flaming cigarette lighter. His hand was badly burned. The woman turned down the job.

Liddy became known for such offbeat suggestions as kidnapping war protest organizers and taking them to Mexico during the Republican National Convention; assassinating investigative journalist Jack Anderson; and firebombing the Brookings Institution, a left-leaning think tank in Washington where classified documents leaked by Ellsberg were being stored.

Liddy and fellow operative Howard Hunt, along with the five arrested at Watergate, were indicted on federal charges three months after the June 1972 break-in. Hunt and his recruits pleaded guilty in January 1973, and James McCord and Liddy were found guilty. Nixon resigned on Aug. 9, 1974.

After the failed break-in attempt, Liddy recalled telling White House counsel John Dean, “If someone wants to shoot me, just tell me what corner to stand on, and I’ll be there, OK?” Dean reportedly responded, “I don’t think we’ve gotten there yet, Gordon.”

Liddy claimed in an interview with CBS' “60 Minutes” that Nixon was “insufficiently ruthless” and should have destroyed tape recordings of his conversations with top aides.

Liddy learned to market his reputation as a fearless, if sometimes overzealous, advocate of conservative causes. Liddy’s syndicated radio talk show, broadcast from Virginia-based WJFK, was long one of the most popular in the country. He wrote best-selling books, acted in TV shows like “Miami Vice,” was a frequent guest lecturer on college campuses, started a private eye franchise and worked as a security consultant. For a time, he teamed on the lecture circuit with an unlikely partner, 1960s LSD guru Timothy Leary.

In the mid-1990s, Liddy told gun-toting radio listeners to aim for the head when encountered by agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. “Head shots, head shots,” he stressed, explaining that most agents wear bullet-resistant vests under their jackets. Liddy said later he wasn’t encouraging people to hunt agents, but added that if an agent comes at someone with deadly force, “you should defend yourself and your rights with deadly force.”

Liddy always took pride in his role in Watergate. He once said: “I am proud of the fact that I am the guy who did not talk.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks