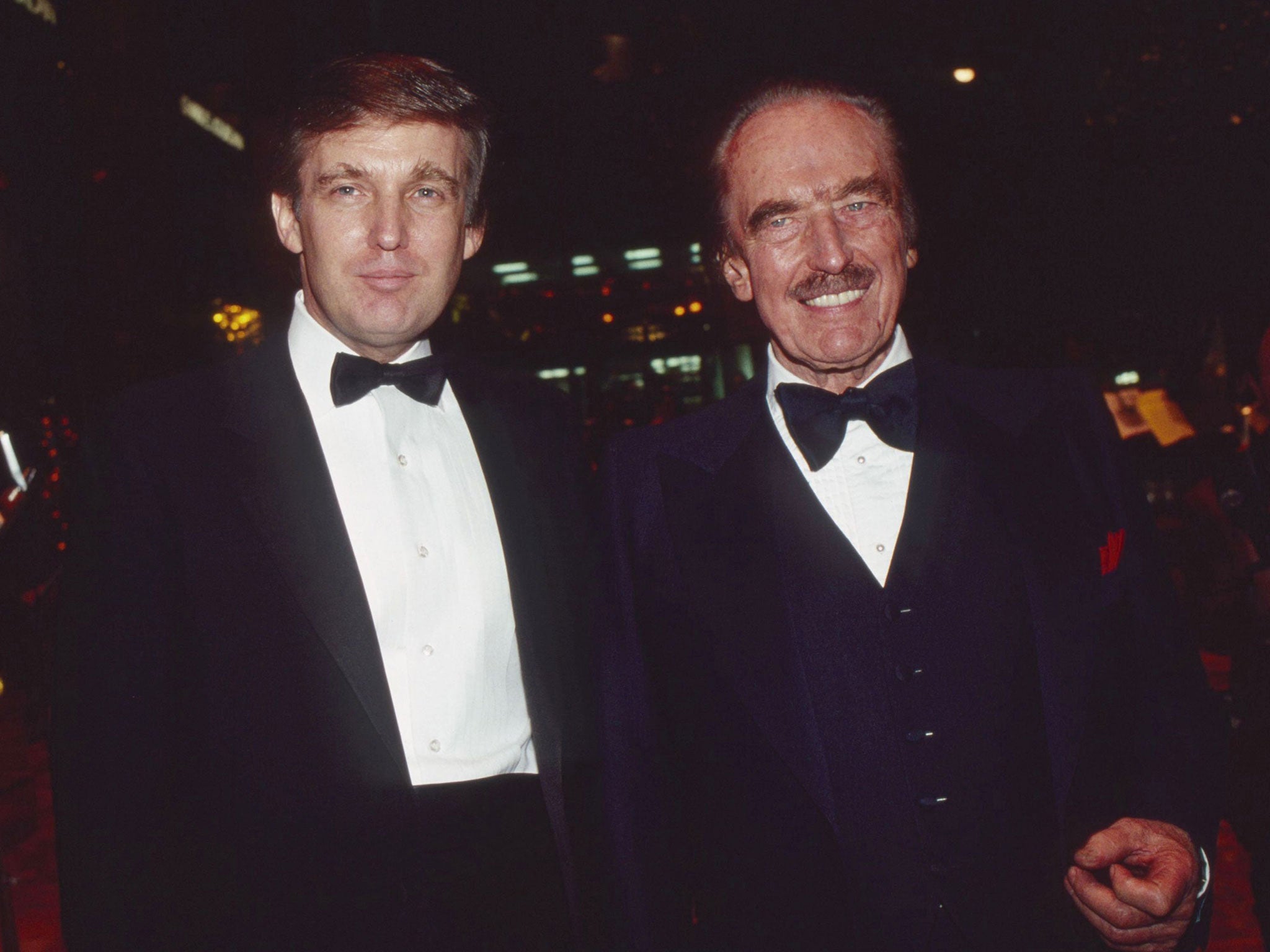

Fred Trump: How the US president’s father built the property empire that spawned his son's billions

The Donald's frequent claims to be a self-made man conveniently overlook huge wealth of his ruthless real estate mogul parent

Donald Trump has long enjoyed presenting himself as a self-made man, claiming the real estate portfolio that brought him wealth and fame is the product of hard graft and vision, nothing more.

“I started off in Brooklyn, my father gave me a small loan of $1m...” he told NBC's Today, without irony, on the campaign trail in 2015.

But The New York Times’s report that the president allegedly participated in “dubious tax schemes” to conceal up to $413m gifted to him and his siblings by their late father Fred Trump has again cast the harsh light of day on the Trump fortune and its backstory.

Frederick Christ Trump (yes, you read that right) built up a huge property empire in the mid-20th century, incorporating 27,000 apartments and row houses in the New York City boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn, while the young Donald was raised in a 23-room, nine bathroom mansion in the leafy middle-class suburb of Jamaica Estates, making a nonsense of his claim to have sprung from hardship.

Fred was born in 1905, the son of German immigrant Frederick Drumpf (a family name the satirist John Oliver has delighted in), who had arrived in New York on 19 October 1885 from Kallstadt via Bremen, a 16-year-old seeking to evade military conscription.

Drumpf initially settled in the Big Apple before relocating to Seattle and then moving on to the Yukon Territory to take part in the Klondike Gold Rush, where he operated restaurants serving horse meat and a string of brothels catering to itinerant miners venturing in from the cold.

A wealthy man, Frederick married Elizabeth Christ in 1902 and returned to New York where he worked as a hotel keeper and where their son Fred was raised in the Bronx.

Fred Trump started his first business venture at 15 in 1920, building garage extensions to existing houses as the automobile’s future at the heart of American life was becoming increasingly clear. Too young to sign the cheques, he became partners with his mother in Elizabeth Trump & Son. He built his first house two years after leaving high school.

Taking advantage of the Great Depression, when Franklin D Roosevelt’s government was doing all it could to bolster the construction and home financing industries, Fred Trump gradually grew his business throughout the 1930s to the 1950s by borrowing from the Federal Housing Authority and making influential friends among the Brooklyn Democratic Party.

His properties were “plain but sturdy brick rental towers, clustered together in immaculately groomed parks”, as his New York Times obituary put it, selling for $3,990 and spread across the low-income neighbourhoods of Coney Island, Bensonhurst, Sheepshead Bay, Flatbush and Brighton Beach in Brooklyn and Flushing and Jamaica Estates in Queens.

He also built apartments for servicemen in the Second World War in Pennsylvania and Virginia and foresaw the advent of supermarkets, building one of America’s first, the Trump Market at Woodhaven, New York, whose slogan was: “Serve yourself and save!”

Known for his thrift, one of Fred’s few luxuries was a Cadillac with a personalised “FTC” vanity plate (his son's is “DJT”). Donald would recall in his ghost-written business manual The Art of the Deal (1987) that his father would roll up at construction sites after the working day was done and collect stray nails from the ground for his carpenters to use again the next morning.

He would also water down paint and manufacture his own disinfectant and cockroach spray to save cash, sending brand samples to labs to determine their ingredients.

“What had cost $2 a bottle, he got mixed for 50 cents,” remembered his son.

Profiled by the trade magazine American Builder and Building Age in 1940, this side of his personality was revealed in depth: “Until last year he never had an office, and carried all his bookkeeping records around in his pocket. The ‘office’ he now has is a little structure of about 90 square feet of space in which the only occupant is a girl to write letters and answer the telephone. He still does most of his office work on the breakfast table at home.”

That office, employee Richard Levy told The Times, was a former dentist’s practice in Beach Haven, Coney Island: “I felt like Custer... There were all these huge wooden Indians all over the place.’’

Fred Trump’s practices were seldom free of controversy. A hard-bitten and ruthless man, he would lie about his family heritage, saying his ancestors hailed from Sweden so as not to deter potential Jewish tenants and developed a reputation for turning away black applicants, frequently bringing him into conflict with indignant civil rights groups.

Amazingly, this was observed and recorded by folk troubadour Woody Guthrie, a Trump tenant, in his poem “Old Man Trump”: “I suppose/Old Man Trump knows/Just how much/Racial hate/He stirred up/In the bloodpot of human hearts/When he drawed/That colour line.”

This especially unsavoury aspect of his character was revived in 2015 when an old New York Times press clipping from June 1927 was rediscovered, recording the 21-year-old Trump’s arrest – and eventual release without charge – for attending a Ku Klux Klan rally in which 1,000 Klansmen became embroiled in a battle with police.

As a father, Fred had hoped his eldest son, Fred Jr, would follow him into the family business and was disappointed, scorning the boy and turning instead to Donald, the class prankster at school.

In The Art of the Deal, President Trump describes the lessons he absorbed from his old man: “I never threw money around. I learned from my father that every penny counts, because before too long your pennies turn into dollars.”

Perhaps more tellingly, he revealed: “I was never intimidated by my father, the way most people were. I stood up to him, and he respected that.”

Donald Trump’s relationship with Fred has often been characterised as combative and oedipal, with the son closer to his Scottish mother Mary McLeod, the inspiration behind his golf resorts in Ayrshire and Aberdeen.

Whereas Trump Sr was largely frugal, although he was vain about his dyed hair in old age, Donald was flashy and flamboyant, vowing to take Manhattan and enter the luxury apartment market, dreaming of building the world’s tallest tower with his name emblazoned on it before turning his eye to the Eastern Seaboard and the gaming tables of Atlantic City, New Jersey.

While Fred may not have shared his boy’s taste for ostentation, he approved of his ambition and did not hestitate to bail him out when his Taj Mahal Casino folly hit the rocks in 1991.

As Sidney Blumenthal recounts in his London Review of Books essay, “A Short History of the Trumps”:

“When the Taj was sinking like Donald’s own private Titanic, Fred Trump rushed to the casino to buy $3.35m in chips to buoy his flailing child, who used the money to avoid default by making an interest payment he wouldn’t otherwise have had the liquid reserves to meet. A straight loan would have put Fred Trump in the lengthy queue of creditors. With his loan in the form of chips he could redeem it as soon as his son had the capital. The New Jersey Casino Control Commission ruled a year later that Fred Trump had engaged in an illegal loan and that Donald should return it, which would have forced him into instant bankruptcy. The Trumps blithely ignored the finding and instead paid a meagre $65,000 fine, though the manoeuvre failed to save the casino.”

When Fred passed away in 1999, The New York Times contacted Donald for comment. His jokey response was extraordinary: “It was good for me. You know, being the son of somebody, it could have been competition to me. This way, I got Manhattan all to myself!”

And he kept it up. As Gwenda Blair wrote in her biography The Trumps: Three Generations That Built an Empire (2000): “At his own father’s funeral, he did not stop patting himself on the back and promoting himself... There was to be no sorrow; there was only success... [It was] an astonishing display of self-absorption.’’

President Trump clearly took his father’s example to heart and sought to surpass his achievements in the New York real estate game.

Whether he received any further gifts from Fred Trump is now a matter for the state’s Department of Taxation and Finance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks