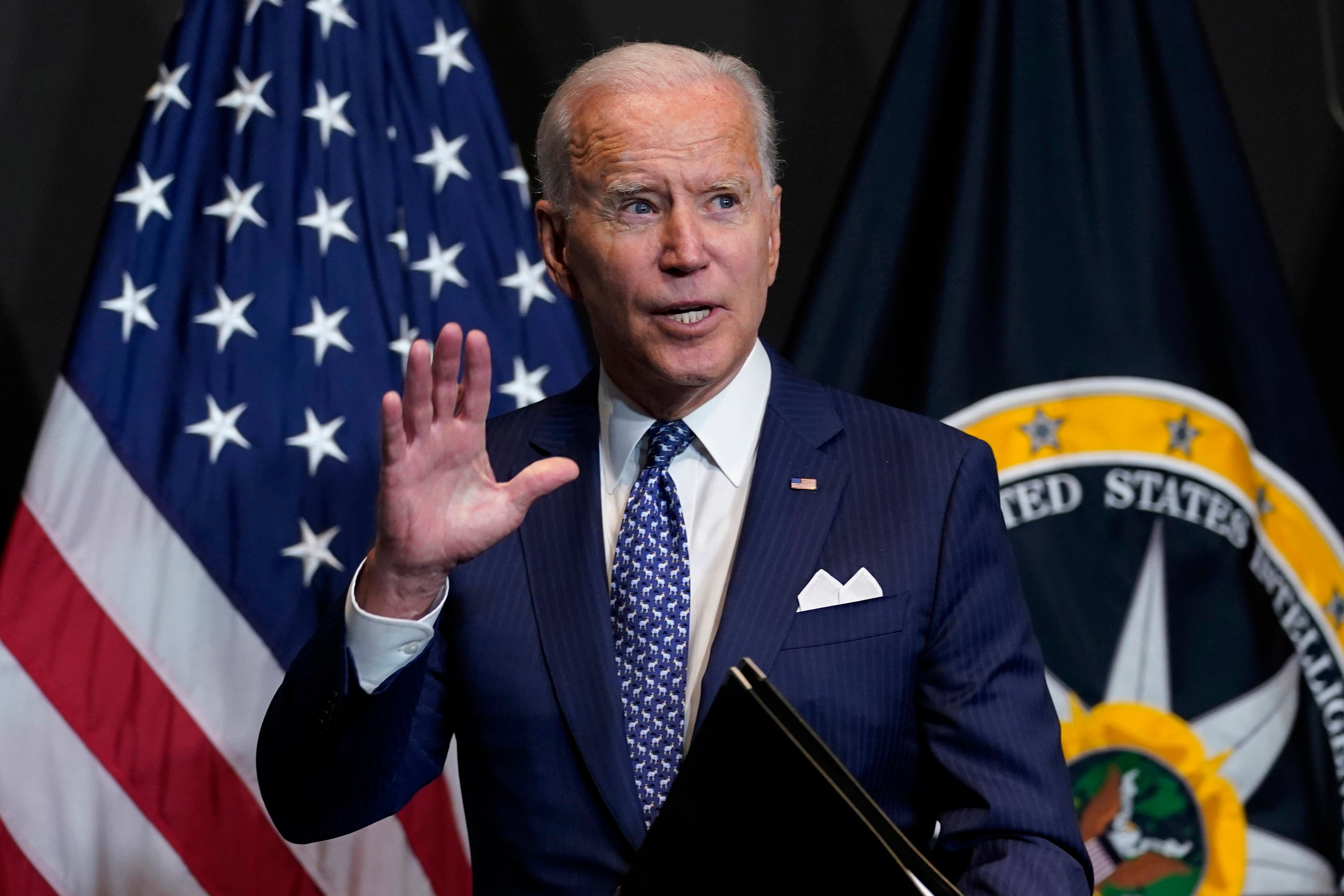

Can Biden's plans manufacture more US factory jobs?

President Joe Biden will be trying to connect with blue-collar workers when he travels to a truck factory in Pennsylvania on Wednesday to advocate for government investments and clean energy as ways to strengthen U.S. manufacturing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.President Joe Biden will be trying to connect with blue-collar workers Wednesday when he travels to a truck factory in Pennsylvania to advocate for government investments and clean energy as ways to strengthen U.S. manufacturing.

The president will tour the Lehigh Valley operations facility for Mack Trucks, a chance to touch base with the plant's 2,500 workers, a majority of whom are unionized. Biden has made manufacturing jobs a priority, and Democrats’ political future next year might hinge on whether he succeeds in reinvigorating a sector that has steadily lost jobs for more than four decades.

The administration is championing a $973 billion infrastructure package, $52 billion for computer chip production, sweeping investments in clean energy and the use of government procurement contracts to create factory jobs. Biden will be briefed Wednesday on Mack's electric garbage trucks.

“This is all part of his effort to lift up and talk about his Buy American agenda as well as the infrastructure package,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Tuesday in previewing the visit.

The president won Lehigh County in the 2020 election, but he is facing the perpetual challenge of past administrations to revive a manufacturing sector at the heart of American identity. Failure to bring back manufacturing jobs could further hurt already ailing factory towns across the country and possibly imperil Democrats chances in the 2022 midterm elections.

Pennsylvania Sen. Pat Toomey a Republican, said Biden should siphon off unspent money from his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package to cover the investments in infrastructure, instead of relying on tax increases and other revenue raisers to do so.

“Hopefully, he will use his visit to learn about the real, physical infrastructure needs of Pennsylvanians — and the huge sums of unused ‘COVID’ funds which should pay for that infrastructure,” Toomey said in a statement.

Deindustrialization has been a thorny problem for Democrats seeking voters during elections.

Layoffs of white factory workers led communities to vote for Republican challengers and turn against Democratic incumbents, according to a 2021 research paper by McGill University’s Leonardo Baccini and Georgetown University’s Stephen Weymouth. They found a connection between deindustrialization and greater racial division as white voters interpreted the layoffs as a loss of social status.

Areas with more factory layoffs also became more pessimistic about the entire economy. The trends documented in the research were most pronounced in 2016, when Donald Trump won the White House while emphasizing blue-collar identity and racial differences.

One challenge for Democrats is that they’re not being forced to deal with the most recent manufacturing job losses, but layoffs that began decades ago.

“Biden would benefit from an improved manufacturing jobs outlook,” Weymouth said. “But a lot of economists think that many of these jobs are gone for good. And so, it’s an uphill battle. There’s alternatives: The president can pursue a more substantial social safety net for people who lose their jobs or investments in these communities that declined for decades.”

Manufacturing has improved since the depths of more than a year ago during the pandemic-induced recession. Labor Department data show that factories have regained about two-thirds of the 1.4 million manufacturing jobs lost because of the outbreak. Factory output as tracked by the Federal Reserve is just below its pre-pandemic levels.

But the manufacturing sector — especially autos — is facing serious challenges.

Automakers are limited by a global shortage of computer chips. Without the chips that are needed for a modern vehicle, the production of cars and trucks has dropped from an annual pace of 10.79 million at the end of last year to 8.91 million in June, a decline of nearly 18% as measured by the Fed. Analysts at IHS Market estimate that the supply of semiconductors will only stabilize and recover in the second half of 2022, right as the midterm races become more intense.

The impact of the chip shortage can trickle through the rest of the economy. Used vehicle prices have shot up 45.2% from a year ago, since there are not enough newly built cars and trucks available. The administration has been proactive in trying to address the problem, advocating for a bill designed to increase semiconductor production in the United States in ways that would also help other manufacturing sectors.

“I am engaging almost daily with industry,” Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said last week at a White House briefing. “We need to incentivize the manufacturing of chips in America. And so, we are very focused on putting the pieces in place so that can happen.”

For the past several decades, presidents have pledged to bring back factory jobs without much success. Manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at nearly 19.6 million jobs, only to slide downward with steep declines after the 2001 recession and the 2007-2009 Great Recession. The figure now stands at 12.3 million.

Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Trump each said their policies would save manufacturing jobs, yet none of them broke the long-term trend in a lasting way.