Julian Assange’s plea deal is more about Biden’s fight for power than justice

According to senior Washington officials, President Biden did not want Assange to be taken to the US for a trial that would infuriate progressive Democrats already at odds with him over Gaza, writes Kim Sengupta

The secret negotiations that led to Julian Assange no longer facing the prospect of being sentenced to up to 170 years in an American supermax prison gathered pace five months ago, when the US Department of Justice indicated for the first time that it would accept a plea deal.

Assange had to plead guilty to a single felony count of illegally obtaining and disclosing national security material. In return he would face no more jail time, after spending five years in custody without trial.

In January, Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese stressed that Assange, an Australian citizen, had spent far too long in limbo. At around the same time, US president Joe Biden stated that he favoured a resolution to the case, which had led to widespread international protests.

Prolonged negotiations then followed, on the charges, the venue for Assange’s court appearance, his support team’s request for assurances that he would not face fresh charges in the future, and whether he might later be granted a pardon over his conviction.

What unfolded has as much to do with US politics as it has to do with the legal process.

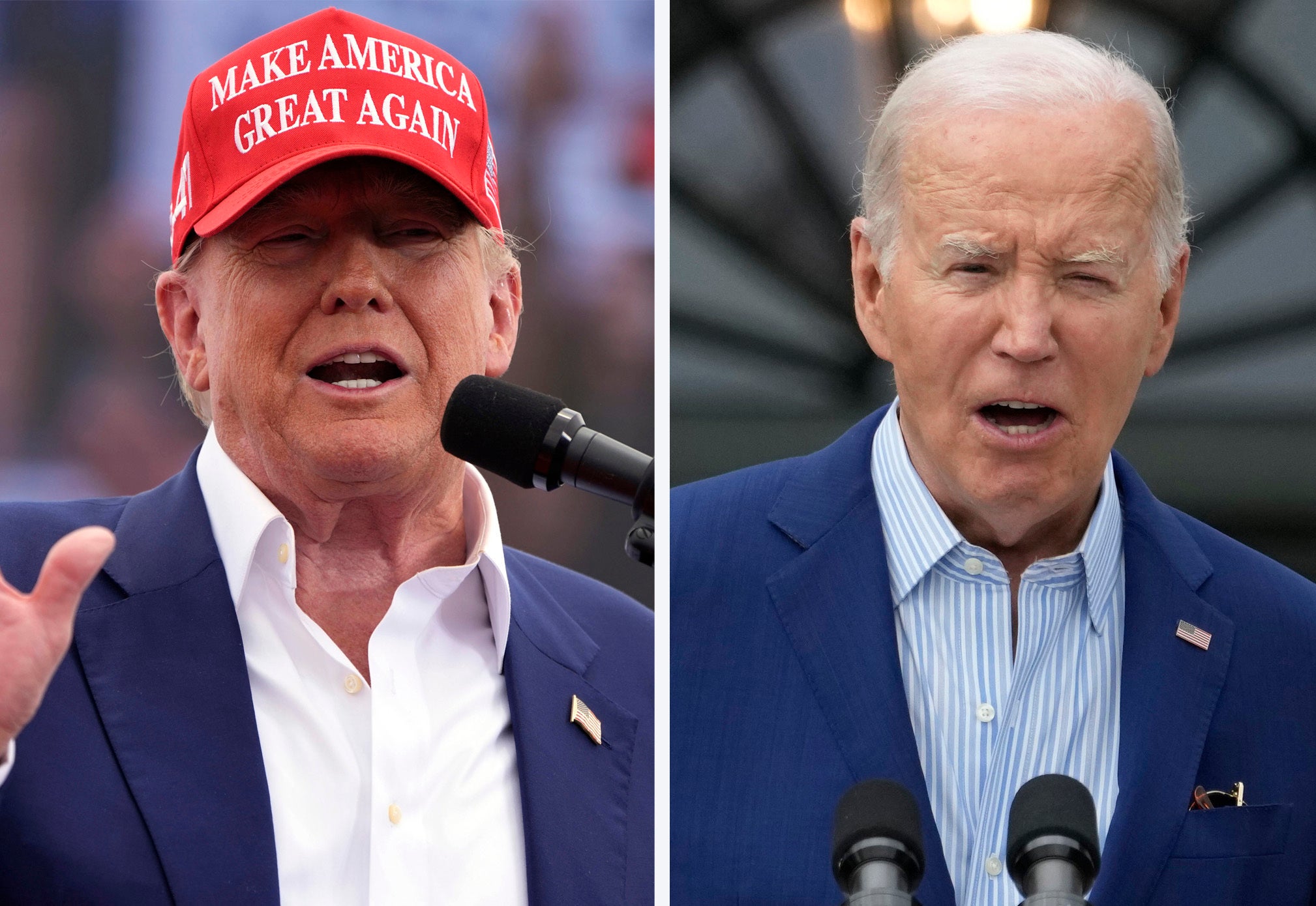

According to senior Washington officials, Biden did not want Assange to be taken to the US for a trial that would infuriate progressive Democrats already at odds with him over Gaza, in an election year in which the president is fighting to stay in office.

But it was the Biden administration that chose to continue to pursue the charges under the Espionage Act that were instituted during Donald Trump’s presidency – reversing the decision of the previous Democratic president, Barack Obama, not to do so because of the ominous precedent it would set for journalism.

The Australian government is said to have proposed three months ago that the list of charges be reduced to one charge of handling classified documents – a misdemeanour – or that other lesser charges relating to hacking could be brought, to which Assange would plead guilty. The justice department rejected these suggestions.

This has led to the theory that some officials in the Biden administration were seeking to punish Assange for something other than the leaking of diplomatic files relating to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, obtained by army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

There were suggestions that they were also after him for the dissemination by WikiLeaks, the platform he founded, of material stolen from Hillary Clinton’s campaign by hackers tied to Russian intelligence agencies in the run-up to the election that helped propel Trump to the White House.

A dozen Russian military intelligence officers from the GRU have been charged in absentia by the US authorities in relation to hacking, with the indictment stating that they had been in contact with WikiLeaks.

A number of people close to Trump are alleged to have been in touch with Assange over the hacking of Clinton’s emails after he sought refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London in 2012.

A prominent figure in this saga was Roger Stone, a long-term and close adviser to Trump, who was later to be arrested as part of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into “Russiagate” and convicted of obstruction of justice, witness tampering, and lying to Congress. His sentence of 40 months in prison was commuted by Trump when he became president.

Stone had talked of having contact with Assange, and at one point instructed a friend, believed to have been the conservative author Jerome Corsi, to “get to” Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy in London and obtain the pending WikiLeaks emails.

He also allegedly told Ted Malloch, a Trump supporter in London, to see Assange. Stone later claimed, speaking to a Republican group in Florida: “I actually have communicated with Assange. I believe the next tranche of his documents pertain to the Clinton Foundation, but there’s no telling what the October surprise will be.”

A British name that came up in relation to Assange and the Clinton emails was that of Nigel Farage, who has close ties with Trump. Farage, who is the current leader of Reform UK, visited Assange at the Ecuadorean embassy in 2017 after returning from a trip to the US. The news of the visit broke after a member of the public saw him go into the building.

A US congressional hearing heard testimony that alleged Farage was a more frequent visitor to Assange than was realised, and that he had passed data on to Assange on “a thumb drive”.

Farage has strenuously denied this. But he has refused to tell a number of news organisations what he did discuss with Assange. He said to me when I asked: “I met Julian Assange just once. I went there in a journalistic capacity, because, like you, I wanted to find out about the emails; no real answer was forthcoming. It is nonsense to say that I met him secretly. Do you think one of the best-known faces in the country can go into the embassy without people noticing?”

During one of Assange’s many court hearings in London, his lawyers claimed that Trump had offered Assange a pardon if he would clear Russia over the Democratic Party emails. They claimed that during a visit to London in August 2017, congressman Dana Rohrabacher had told Assange that “on instructions from the president, he was offering a pardon or some other way out, if Mr Assange ... said Russia had nothing to do with the DNC [Democratic National Committee] leaks.”

Rohrabacher denied the claim, saying he had made the proposal on his own initiative and that the White House had not endorsed it. “When speaking with Julian Assange, I told him that if he could provide me information and evidence about who actually gave him the DNC emails, I would then call on President Trump to pardon him,” he said.

Assange has been repeatedly critical of Clinton in relation to her attempts to indict him over the original Iraq and Afghanistan exposures, and also of her part in formulating American foreign policy, which has supported intervention in a number of overseas conflicts. He opposed her presidential bid. But he has never been charged over the Democratic Party computer hacking.

Assange has experienced appalling privations while incarcerated in prison for many years under extremely harsh conditions for carrying out legitimate investigative journalism. The expected life of freedom in Australia will be a huge relief for him and for his long-suffering family. It will also be a relief that he will be far away from America and from the toxic fallout that is likely to surround the coming presidential election.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks