Why has the number of Americans killed or wounded in road-rage shootings doubled in the past year?

Politicisation of gun-violence debate obscures line between statistics and spin, writes Justin Vallejo

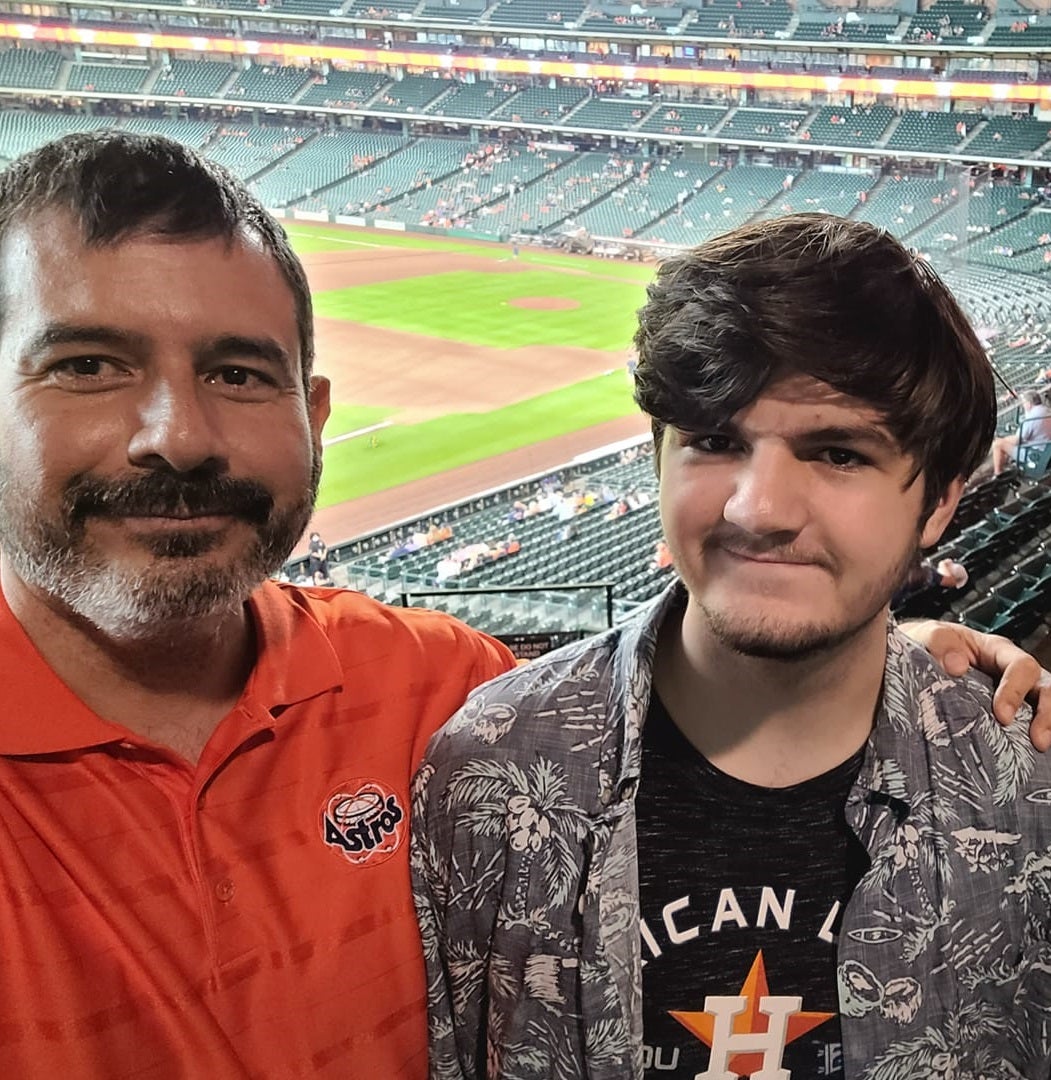

David Castro had questions.

Which university to attend? Either Texas A&M or Purdue. What to study? Probably chemical engineering. What could he do about the environment, global warming, and gun violence?

"He had a wry and dark sense of humour, and would say ‘what’s going to happen if they pass laws that allow anybody to carry a sidearm, will everyone just shoot everybody when they get mad’,” his father Paul Castro tells The Independent.

"He was nervous about it, but he parked it. We would talk about it when it came up."

Leaving Minute Maid Park with his dad and brother on a Tuesday night in July, David was just a 17-year-old kid celebrating the Houston Astros win over the Oakland Athletics, placing his team on the top of the MLB’s AL West standings.

It was an exciting game and David was excited about getting his driver’s licence in a few weeks. His dad was giving fatherly advice on the road, telling him to stay calm in traffic and warning him that people can get irrationally mad.

A white, Buick LaCrosse with a single paper licence plate on the back pulled into a side lane and tried to cut in front of Mr Castro’s pick-up truck at the bottleneck, before the driver leaned out the door and started yelling.

“I point both hands toward the lane like to show, ‘dude, I’ve already let three cars in’. I didn’t flip him off. I wasn’t shaking my face,” Mr Castro says. “The amount of damage that bullet did, it created inoperable damage. David died on the spot,” he adds.

More than a week after Mr Castro and his two sons were chased at high speed and fired upon in the streets of Houston, the shooter who killed David with a 40-calibre round “over a perceived slight to his manhood” remains at large.

The “execution” leaving that baseball game leaves David’s question on gun violence lingering as road-rage shootings doubled in the past year and the country recorded the largest increase in homicides in its history.

Drilling into the search data of the Gun Violence Archive tells only part of the story behind the 6 July shooting, listed simply as incident ID 2055654, at the address of 600 block of McCarty Street, Houston Texas.

A day earlier, there was incident 2054806 in Troy, Michigan at 3990 Rochester Rd. A day later there was incident 2055846 in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, at 8601 W Commercial Blvd. Two more shootings. Two more dead.

The number of road-rage shootings leading to death or injury almost doubled from a monthly average of 22 in the four years before May 2020 to a monthly average of 42 between June 2020 and May 2021, according to an analysis of the archive data by gun control advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety.

In 2016, 241 people were shot and killed or wounded in a road-rage incident compared to 212 so far this year. Everytown’s director of research, Sarah Burd-Sharps, projects that number to reach an all-time high of 500 by the end of 2021 if current trends continue.

It’s unclear to Ms Burd-Sharps what is driving the increase, but she says it follows a national trend line in shootings across the country.

The road-rage statistic is gaining national prominence in gun violence conversation following the release of the Everytown research in June, and promotion from its affiliated group, Moms Demand Action.

In a statement shared by email, Moms Demand Action founder Shannon Watts says road rage incidents happen all over the world but only in America, where angry drivers have easy access to guns, do they turn deadly.

“But instead of supporting common-sense solutions that will keep guns out of the hands of people who shouldn’t have them, the gun lobby and its allies continue to pursue a dangerous agenda of guns for anyone, anywhere, any time – no questions asked,” she says.

That gun lobby is most commonly associated with the National Rifle Association, which did not immediately respond to interview requests for this story.

The politicisation of the gun violence debate by the gun lobby like the NRA and the anti-gun lobby like Everytown, backed by former Democratic presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg, obscures the line between statistics and spin.

Jerry Ratcliffe, a professor of criminal justice at Temple University, warns against comparing year-over-year crime figures, especially in low-frequency events like road rage with a gun, given the size of the country and level of gun ownership.

For every blitz on road rage or media event highlighting it’s getting worse, there may be other jurisdictions with reductions that are not advertised, Mr Ratcliff says.

“It generates confirmation bias because we probably are unaware of all the towns where road rage has declined. It just doesn’t get advertised,” Mr Ratcliff says, adding that the GVA’s national data is more reliable than anecdotal reports from specific places.

“The trend does seem to be increasing. It is especially concerning given there were fewer people driving during the pandemic, so we would expect fewer road rage incidents,” Mr Ratcliffe says.

“It could be possible that any decrease associated with the reduction in total driving miles across the country during the pandemic might, unfortunately, be offset by the increase in gun ownership over the same period.”

The Federal Bureau of Investigation only tracks murders, not shootings, let alone road-rage shootings. Its Uniform Crime Report data is not in real-time, and its annual release this September will be the last in its current format before switching to a new reporting structure.

The data that is available show that 2020 recorded the largest increase in homicides in the country’s history, and the trend is continuing in 2021. Other violent crimes, meanwhile, have been moving in other directions.

As go the murders, so would go the road rage shootings, says Jeff Asher, a former CIA officer turned crime data analyst, who has been tracking the oscillating violence across the country.

He says the Gun Violence Archive, which is based on media reports as opposed to law enforcement record-keeping, can accurately identify trends while not being precise in pinpointing the data behind them.

“For example, it might say 220 people were shot and killed over July 4, but we don’t actually know that. We know there are reports. Some might have been justified, suicide, we don’t know for sure,” he says.

But if the archive is compared year over year, he adds, it’s a decent indicator that fills an important gap in that national data gathering that doesn’t allow real-time tracking.

As cities like New York and Chicago grapple with increasing gun violence in real-time, and families like the Castros suffer the consequences in real life, Mr Asher has been following the trends over the past two years to identify what, if anything, is behind it.

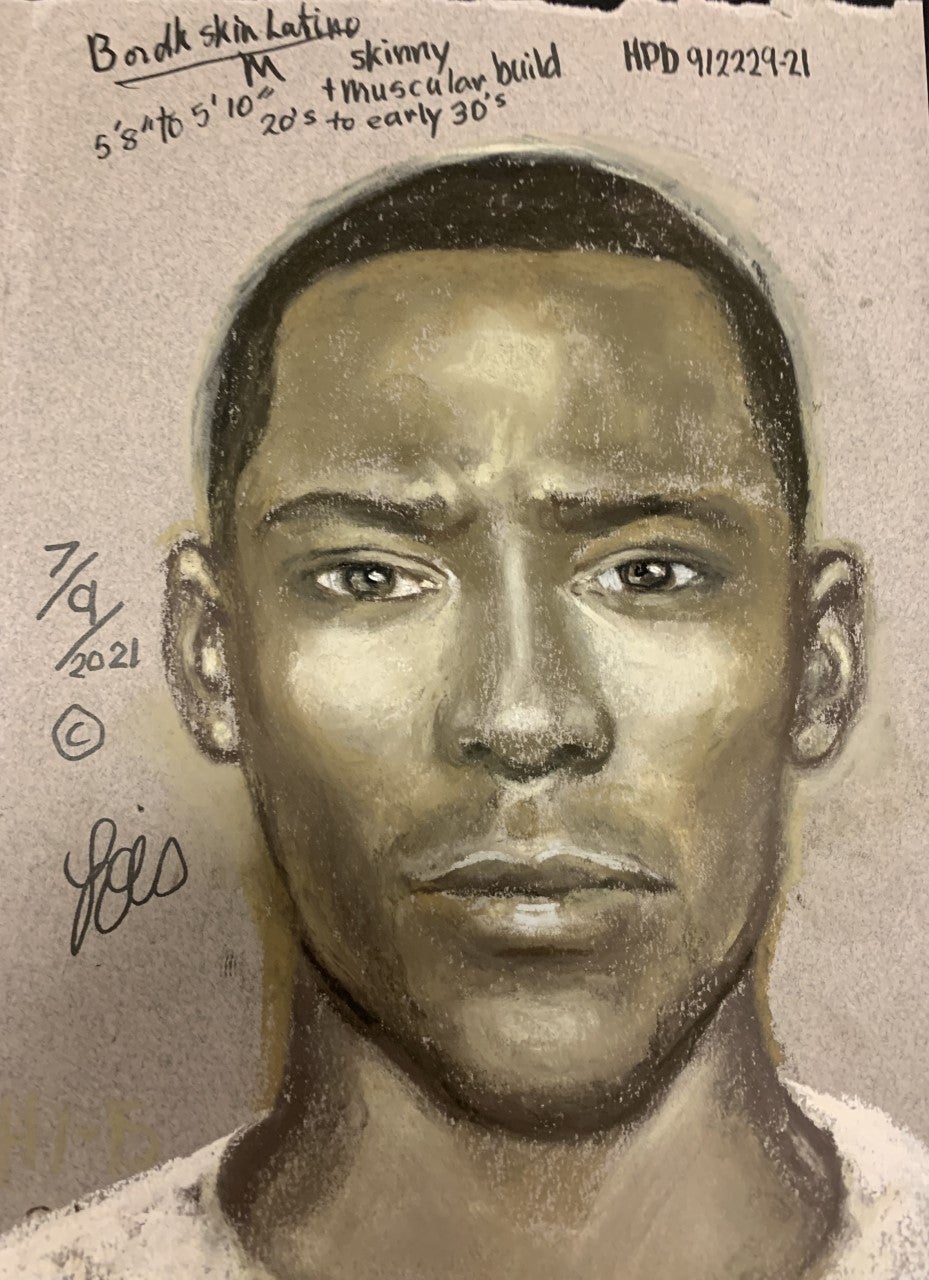

Like most things, the reasons are complicated. None of which neatly explain why Mr Castro and his sons were pursued several miles by a man who police believe could be from out of town, aggressively swerving through traffic, flashing lights and getting “almost chipping paint” close before firing into their truck as they passed him in a U-turn. A $10,000 reward is being offered for his arrest.

It’s plausible that stresses of the pandemic contributed to the rise in shootings, with murder up in the early stages of the lockdown. But it’s too simplistic to say it was just the pandemic, Mr Asher says.

Murders elevated during a summer of protests, but they generally elevate during the summer before declining in the winter.

There’s a legitimacy crisis in law enforcement and the criminal justice system, and the de-policing of officers less likely to stick their necks to make stops and arrests. That creates an environment where more violence can happen. But then, why are only murders increasing while other crimes remained level or declined.

There are historically high numbers of people wanting to own guns, with firearm demand exploded during 2020 when the FBI conducting a record 39.7 million background checks – a 40 per cent increase, according to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System.

“All of this comes together, with a tonne more guns, all of this anger and other issues all combining; put that all into a jar,” Mr Asher says.

After staring at the data and the reasons driving it, no obvious cause, and therefore no obvious solution, presents itself.

“And I think that’s the issue. You look at what Joe Biden might want to do and there aren’t a lot of easy fixes on what the federal government can do beyond funding programmes,” Mr Asher says. “You can’t flip a switch.”

What the president can do is fund the police.

Mr Biden has offered $350 billion to put more police boots on the ground and this week met the country’s national law enforcement and local city leaders, including the likely next mayor of New York, Eric Adams.

Mr Adams calls himself the new face of the Democratic Party after winning the mayoral primary on a platform opposing the far left’s “Defund the Police” sloganeering.

He criticised Democrat lawmakers as misplacing priorities in addressing gun violence while ignoring the cities where people are dying the most.

“It’s almost insulting what we have witnessed over the last few years,” Adams told CNN’s Jake Tapper on State of the Union.

“Many of our Presidents, they saw these numbers. They knew that the inner cities, particularly where Black, brown and poor people lived, they knew they were dealing with this real crisis. And it took this president to state that it is time for us to stop ignoring what is happening in the south sides of Chicago, in the Brownsvilles, in the Atlantas of our country.”

Mr Adams’s comments, and his seat at the president’s table, mainstreams what has historically been dismissed as a right-wing talking point: that the major issue in gun violence is black-on-black shootings in Democrat-run cities like New York, Baltimore, and Chicago.

The Second Amendment argument focuses on inner-city shootings in its message against new laws restricting legally obtained firearms, the kind more often seen in mass shootings, as opposed to focusing on illegally-obtained firearms used more often in inner-city shootings. Gun control doesn’t prevent gun violence when gun violence is committed by uncontrolled guns. Something like: AR-15s don’t kill people, Glock 19s kill people.

Either way, people get killed. As Mr Castro says, the “broken” gun violence debate didn’t prevent his son from getting killed when a man, described as Black or Hispanic in his 20s or early 30s, put his arm out the window and pulled the trigger.

Mr Castro comes from a gun-owning family, though owns none himself, and is not in principle anti-gun, though he is anti-proliferation of guns and ease of buying the high-calibre bullets, “that destroyed my son’s heart”.

“I think that the great majority of Americans are not represented by either of the groups that are talking the loudest. There are many common sense people but it’s the extremes that raise the money and own the conversation,” Mr Castro says.

“I have unimaginable anger and sadness.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks