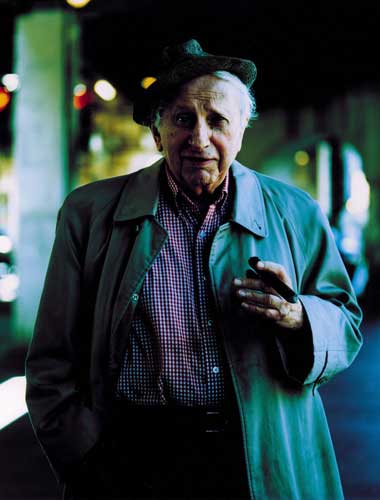

US mourns Studs Terkel, who gave a voice to ordinary folk

Writer and oral historian who teased out the often extraordinary stories of 'uncelebrated lives', dies at the age of 96. David Randall reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Studs Terkel, the resolutely liberal broadcaster and writer whose work gave voice to the experiences of ordinary Americans, has died aged 96.

Terkel had suffered from ill-health for a number of years, but perked up in 2005 after open heart surgery – the oldest person to undergo such a procedure. Yet two weeks ago he suffered a fall at home. He had survived previous tumbles, joking after one: "I was walking downstairs carrying a drink in one hand and a book in the other. Don't try that after 90." This time, however, there was to be no revival, and he died peacefully at home on Friday. By his bedside was a copy of his latest book – PS: Further Thoughts From a Lifetime of Listening, due out next month – at least the fourth he had produced in his nineties.

Senator Barack Obama, a fellow Chicagoan whom Terkel hoped to live to see elected president, said Terkel was a "national treasure", and added: "His writings, broadcasts and interviews shed light on what it meant to be an American in the 20th century." Through his daily radio show, produced by WFMT Chicago but widely syndicated, he teased from the kind of folk he called "the uncelebrated" stories of their experiences through the Depression, war, civil rights battles, and everything from involvement with the Ku Klux Klan to the heyday of New Orleans jazz.

At the age of 45 he began collecting such material in book form, writing more than a dozen bestsellers and winning a Pulitzer Prize in 1985 for his volume of Second World War memories, The Good War. Other notable Terkel productions were his first book, Giants of Jazz (1957); Working: What People Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1974); and an oral history of race relations called Race: How Blacks and Whites Think and Feel About The American Obsession (1992). "If I did one thing I'm proud of," Terkel said last year, "it's to make people feel that together, they count." Not surprisingly, he was a lifelong non-driver, preferring to chat to cab drivers or fellow travellers on public transport.

He was born Louis Terkel in May 1912 – "as the Titanic went down, I came up". His father, Samuel, was a tailor; his mother, Anna, a seamstress. In 1922 the family moved to Chicago and ran a rooming house where he met workers, activists and itinerants. It was while studying philosophy and law at the University of Chicago that he got his nickname, from the character Studs Lonigan in James T Farrell's trilogy of novels about an Irish-American youth from the city's South Side.

He worked briefly in the civil service, then moved to radio where he acted, was a disc jockey, and, in the 1940s, began interviewing. From 1949 he was the star of a national TV show called Studs' Place, set in a fictional bar – which some viewers would go looking for in Chicago. His TV career came to a halt in 1952 when his liberal views and support for labour unions meant he was blacklisted by McCarthyites. But his Chicago radio station remained loyal and The Studs Terkel Program went out every weekday for 45 years, until he was 85. Besides the inhabitants of Main St, USA, he also interviewed such celebrities as Bob Dylan, Leonard Bernstein, the reformed Ku Klux Klansman CP Ellis, Bertrand Russell and the bluesman Big Bill Broonzy.

In 1939, he married Ida Goldberg, a social worker, a partnership that lasted until her death 60 years later. Her lifelong regret was that she'd never got the old so-and-so to dance. He said of her, "Ida was a far better person than I, that's the reality of it", and in an interview with Mother Jones magazine in 1995 he told a story that illustrated this, and the journalistic instincts that prised so much information from his subjects. It concerned his research for Hard Times, his book on the Depression.

"I had to get a caseworker, a social worker. Well, my wife was a social worker during the Depression. And I thought, hmm, she'd be good. I'll change her name... She was telling about this one white guy, an old-time railroad worker. She remembers him as a distinguished-looking guy, grey hair, he's on relief, and she was given orders to look into the closets of these people. As she's telling me this, of course she starts to choke up. She says she looks in his closet and it was empty. And she says, 'He was so humiliated, and I was too.' It was a horrible moment – but I call it a marvellous moment for me, to capture what it was like being humiliated. And as she is choking up, I'm saying, 'This is great! This is great!' And she says, 'You bastard!'"

Yeah, but what a bastard.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments