What has Donald Trump really done for the rust belt states?

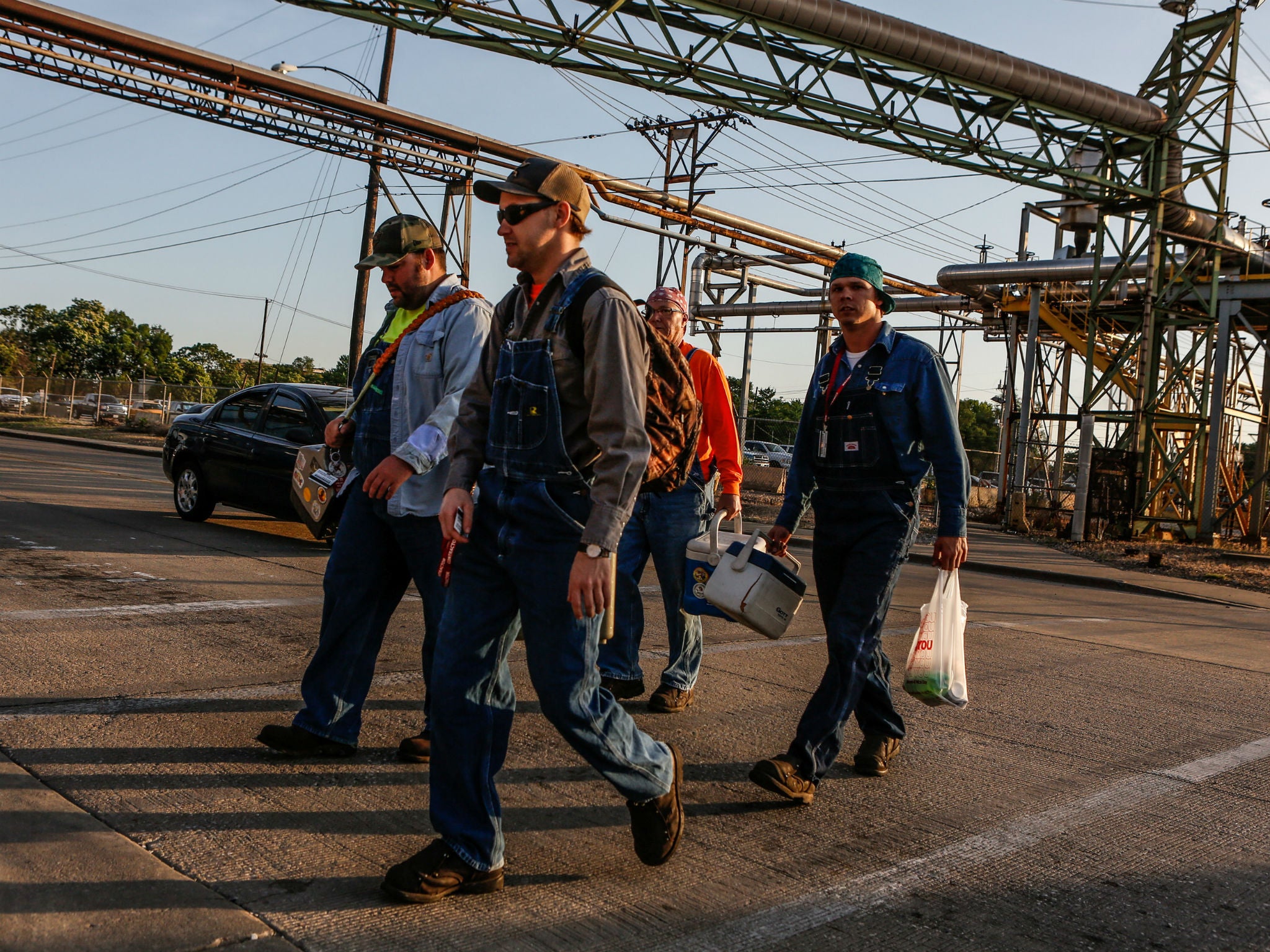

Blue collar voters in key industrial swing states delivered for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. But has Trump delivered economically for the rust belt over the past four years?

In perhaps the most memorable image in his inauguration address in January 2017, Donald Trump lamented the “rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation”.

The “rust belt” generally refers to American states around the Great Lakes region of the northwest including Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

They were prosperous centres of coal mining, steel production, heavy industry and manufacturing in the early 20th century.

But their fortunes turned in the domestic recessions of the 1970s and the rise of domestic and foreign competition. This decline accelerated in the 1980s as much manufacturing automated and shed jobs, and the US shifted resources from industry into services, leaving many disused factories to “rust”.

What industry remained was then hollowed out further by the “China shock” of the 2000s, when China entered global manufacturing trading networks at huge scale and began overproducing steel and depressing demand on world markets.

The rust belt means places like Scranton (Pennsylvania), Gary (Indiana), Detroit (Michigan) – names that have become resonant with industrial decline, population loss and its attendant human misery over the past half century.

Trump made the plight of the rust belt a central feature of his 2016 campaign, making extravagant promises to resurrect American steel production, reinvigorate domestic manufacturing and bring back jobs.

This was, to a considerable degree, an electoral calculation.

The rust belt contains some important “swing states” – states that traditionally teeter between the two main parties – such as Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan.

Trump’s team believed he could wrestle blue collar rust belt voters away from their traditional allegiance to the Democrats.

And the strategy succeeded. Trump managed to flip Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan from Democrat to Republican and the electoral college votes from those states helped to deliver him the White House.

But has Trump delivered for those voters over the past four years?

What has Donald Trump done for the rust belt?

One of Trump’s primary economic policies over the past two years has been protectionism.

He imposed 25 per cent tariffs on steel imports from China and also Europe in 2018, claiming this would help domestic steel producers by reducing competition from imports.

The volume of steel imports did fall, but there has been scant evidence of any gains from that for the domestic steel industry and it workers.

Employment in the steel industry in the rust belt states was largely flat even before the coronavirus pandemic struck the US economy.

Though steel prices rose in March 2018, which helped domestic producers’ profit margins, they have been falling for most of the period since.

The share price of US Steel, one of the biggest national employers and producers, is now below where it was when Trump was elected. The rest of the stock market is higher.

Moreover, it seems the initial spike in domestic steel prices resulting from those tariffs on imports hurt the industrial consumers of steel in the rust belt more than they helped steel producers.

One analysis suggests that steel and aluminium tariffs resulted in at least 75,000 job losses in metal-consuming US industries by the end of 2019.

The costs of car manufacturers such as Ford and General Motors rose, prompting them to shed jobs. Last year, General Motors closed its Chevrolet plant in Lordstown, Ohio, shedding its final 1,500 jobs.

The number of jobs in car manufacturing in Michigan, the heart of the US industry, declined by around 4,000 to 36,000 between the beginning of 2017 and September 2020.

Broader manufacturing jobs in these states also stagnated between 2017 and 2019.

Calls for people to “Buy American” seemed to be making little substantive impact. And then came the pandemic.

Overall unemployment in some rust belt states, such as Michigan and Ohio, shot up more rapidly than elsewhere in the US earlier this year.

Another Trump policy has been to exert pressure on US companies to increase investment domestically.

There was a spate of announcements early in Trump’s presidency of factories expanding or of firms reshoring production. But the flow of announcements has dried up.

Peter Navarro, Trump’s economic adviser, insisted last year that “billions of dollars are being invested in new or rejuvenated mills and foundries all across America”.

And Trump himself claimed in June 2019 that “now we have many [car] plants being built all throughout the United States”.

Yet there was no statistical evidence of an investment boom in the rust belt states, automotive or otherwise, before the pandemic and there certainly isn’t now.

Poverty rates in the rust belt states did fall between 2017 and 2019 according to the US Census Bureau, although these declines were broadly in line with the national average.

And the bulk of the gains from Trump’s 2017 tax cut went to the wealthy, not to blue collar workers in the rust belt.

The impact of Trump’s policies on America’s rust belt has been broadly what economists had predicted when he started talking up the economic merits of protectionism in 2016.

That is to say, it did more harm than good overall. And to even those sectors which did initially benefit, the boost did not last.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks