Can Joe Biden bid farewell to the most fractious four years in modern American politics?

Everyone had their own moment, writes Andrew Buncombe, when they realised this was no longer politics as normal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If there was a single moment when it was rammed home how these four years were going to be so different, it was on a chilled night at JFK airport as people demonstrated against Donald Trump’s Muslim travel ban.

Everyone will have their own such instance, of course. Perhaps it was the June day Trump swept down the escalators at Trump Tower to announce his candidacy and denounce Mexicans as rapists. Perhaps it was when he misogynistically attacked Megyn Kelly for asking a very reasonable question of him at the first Republican debate.

Maybe it was when he sent out the White House press secretary to lie about the size of the crowds on inauguration day, when he had delivered a speech co-authored by rightwing hardliners Steve Bannon and Stephen Miller.

Yet that night at JFK, never the friendliest of places to new visitors, it felt this usually welcoming nation had transformed into a world of sheer insanity. In one fell swoop, Trump’s ban on entry to the US for residents of seven Muslim-majority nations triggered chaos and confusion across many of the world’s airports, as people were turned away from their flights.

In New York, Hameed Khalid Darweesh, an Iraqi man who had worked for the US military for 10 years and whose life had been threatened as a result, was detained as he sought to enter the country. Eventually, he was permitted to do so, after appeals from his lawyers and members of the US military.

“America is the greatest nation, the greatest people in the world,” Darweesh said, sobbing, when he stepped out of the airport.

It does not really matter which moment you choose. Most people, both Trump’s supporters and his critics, agree his presidency has marked a unique period in US politics.

Trump himself suggests he is better than any other president since Abraham Lincoln, and perhaps better than him as well. The polls do not agree; while Trump has maintained a little-shifting approval rating in the low 40s, that has represented an at times historic low.

One could make a case that in terms of actual, measurable harm done, that the two terms of George W Bush are on a far graver scale than Trump’s four years. He ordered the invasion of Iraq, on false claims and intelligence, that probably resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Iraqis, and thousands of US and UK troops. He also refused to ratify the Kyoto treaty on climate change; another denier of science.

Though Bush only left office in 2009, it is often forgotten that his opponents said much the same about him as Trump’s do about him. There were protests in the streets, political conversations became strained, and friends fell out. Celebrities vowed to move to Canada or Europe but ended up staying in Los Angeles.

(Historians also remind us that the US did have an actual civil war, from 1861 to 1865, which resulted in perhaps more than 600,000 deaths.)

For critics of Trump, what is different about him compared to Bush is that he has stoked and driven divisiveness to a degree not seen before. This may be in large part due to his use of social media. A Twitter bully willing to use that powerful platform to attack a former Mexican beauty pageant contestant in the middle of the night, to attack women as “nasty”, and to call people dogs.

This has real effects. If people see language and views being voiced by the highest elected official in the land, they feel empowered to do the same and to act on those sentiments. That is why groups that monitor hate speech and racism say they have seen this surge over the past four years.

One of America’s most powerful weapons, in part in the form of movies and television and literature – is the image it sells of itself, not simply to its own citizens but to the world – a nation of fairness, and civility, of people striving, where people can achieve greatness and overcome any barrier by dint of their labour and persistence.

Millions of Americans – people of colour, the poor, the disenfranchised, those whose ancestors were brought to this country as slaves and whose labour resulted in both the nation’s primacy and its white supremacy – know this to be a dream rarely realised. And yet it persists.

Part of the fantasy is of a politics and civility and fair debate. Where representatives worked “across the aisle” for the betterment of everyone, where citizens voted for the best candidate, regardless of party. Where the president, who is not just the leader of the government, but the head of state, represented all Americans.

This remembrance of an imagined golden era is probably overplayed. American politics has always been cut-throat and frequently vicious, just as in other countries.

What feels true, however, is that tribalism has taken over politics entirely. Since Newt Gingrich became speaker of the House of Representatives in the 1990s and vowed to oversee a radical overhaul, such partisanship has intensified. Nowadays there are fewer “moderates” from each party, especially among the Republicans, whose shift to the right started with Gingrich, was followed by the Tea Party and has continued under Trump. Dozens of moderates from the GOP have either lost their seats to conservative challengers or else quit.

Democrats have also moved to the left.

What has been fascinating covering this election campaign is to hear supporters of both candidates decry the absence of “moderates”. They also dislike the fact they no longer have friends from the opposite party. One woman at a Trump rally in Iowa told me of friends of hers who had been disowned by their teenage children because of their support for the president.

Yet when asked which Democrats from the past they have in mind of a moderate, many Trump supporters fail to name anyone. Democrats point to the likes of Susan Collins of Maine, who may well lose her seat this year.

Was it that the nation’s politics, hampered by the two-party system was always divided, only more so now. Has social media made it more plain? There are certainly fewer independent voters now. Why is that? The big difference is that everyone now feels the need to take a side.

If Joe Biden is elected, is he going to do anything to fix this, to heal the nation?

In some ways, as his critics point out, he is part of the problem, part of a political system for the best part of five decades, that has failed to deliver to millions of Americans, a society in which social migration has slowed. He is a man accused of helping wreck the chances of a generation of young African Americans with his championing of the 1994 Crime Bill, that discriminated against Black communities, accused by his very own running mate of failing to call out segregationists in the Senate.

One thing we might hope for from Biden is that he is just more boring than Trump. Less Twitter, less noise, less drama. He has served in government and shown an ability to not need to be the loudest person in the room.

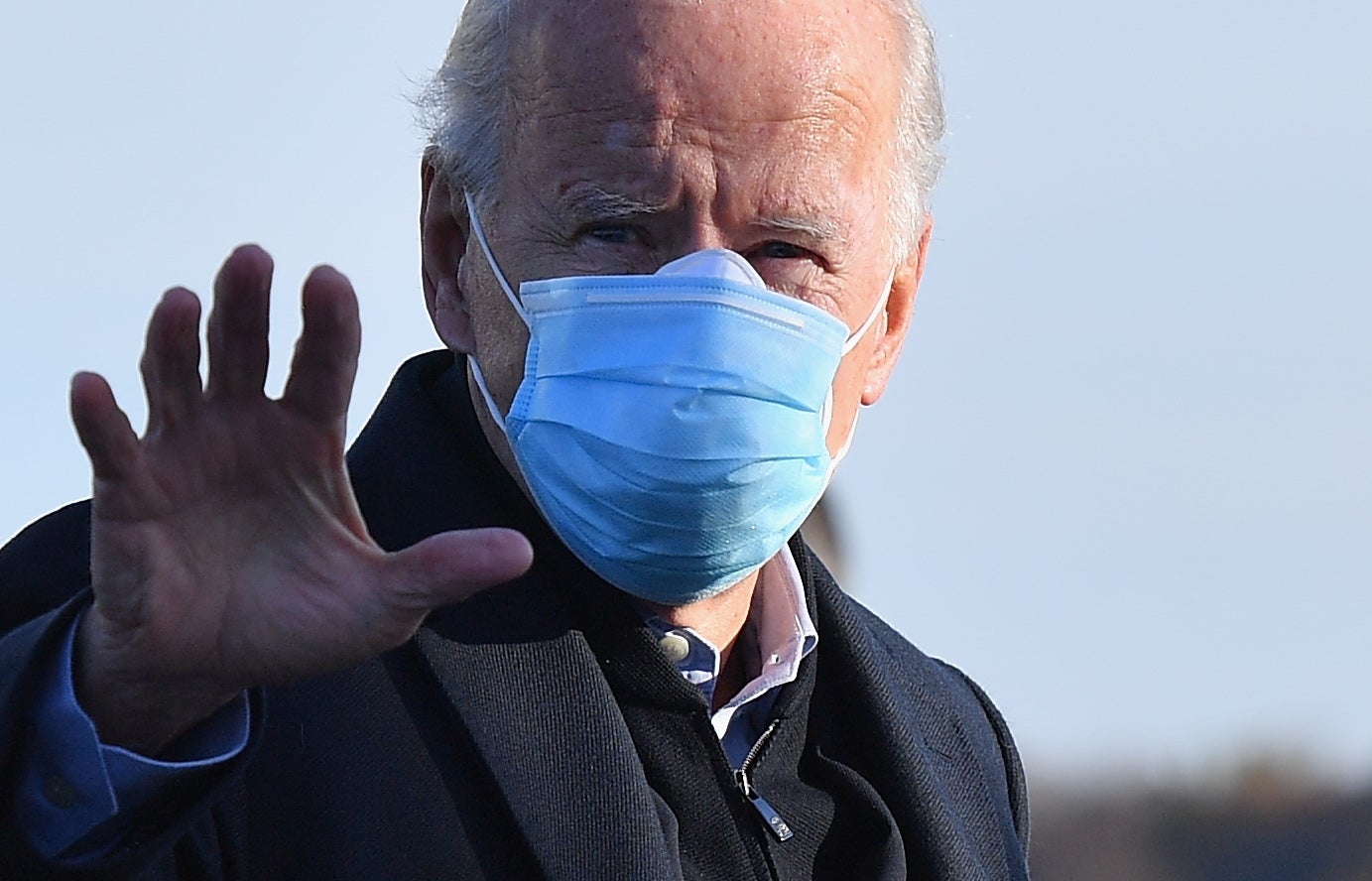

We can assume he will listen to scientists rather than insult them. We can assume, given his careful, limited and socially distanced campaigning, always wearing a mask, that he will continue to promote such policies when he steps into office.

He will need to. Already the death toll in the US stands at 230,000. By the time he takes office, we can only imagine what it may be. One of the first challenges he will have is to oversee the production and distribution of a vaccine.

This will need care and compassion. Many say they do not feel safe taking a vaccine. They will need to be won over with dignity, not mocked or derided.

Biden insists, repeatedly, in the inherent decency of America and its people. They may be no more or less decent than in any other country, but that misses the point; the fact Biden believes in it suggests he will try and act in such a way.

His willingness to try to avoid Trump’s aggression and belligerence, as evidenced by his performance at the debates, and in talking to members of the public who question him, also bodes well.

Biden may not have Trump’s boundless energy, but that may be a good thing. He probably understands how weary so many people are with all this noise and chaos.

Biden will also need rapidly to stabilise the economy, support businesses still struggling to deal with the fallout from the pandemic and act to calm the markets. As he says, he and Barack Obama did this before, after the 2008 financial crisis. It may be Biden is a transition president, one whose running mate occupies that slot, sooner rather than later. In Kamala Harris, he has picked a historic choice.

Yet one thing the Trump presidency has reminded anyone living in his country is that politicians only play a limited role in building a society.

What the pandemic has underscored, and the racial protests have shown, is that America is still an idea in development. The way forward, surely, requires helping others access the opportunities shut off to them, creating a truer, deeper more engaged and empowered country.

After four years of turmoil and disruption, who deserves credit for standing up against hate and dishonesty and prejudice, for supporting facts and science?

Everyone will have their own list.

One might include the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; the medical staff who risked their lives to help those infected by the coronavirus; the women who marched on the National Mall after the president boasted about sexually assaulting women; the students from Parkland, Florida, who ignored those who said they could not take on the powerful NRA; the community activists in north Minneapolis who organised the supply of food and medicine after protests over the death of George Floyd turned violent and destroyed stores; young climate change activists of the Sunrise Movement and Greta Thunberg, who told Trump and other world leaders they had failed young people; Stacey Abrams, who refused to be told Black women could not challenge for the governorship of Georgia; Heather Heyer, who was killed while protesting against white supremacists in Charlottesville; Fiona Hill, the British-born Russia expert who testified during the impeachment hearings that her job was to serve whatever president was in power regardless of party affiliation; the mother of Breonna Taylor; the lawyers, some who worked pro bono, to help Hameed Khalid Darweesh and a second Iraqi to enter the county where they had been promised safe haven.

They are just some. There are many others. What heroes will the next four years throw up?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments