The rise of hoax news: How a shameful new industry is profiting from war

The extremely online nature of modern warfare has spawned a cottage industry of scammers, fraud artists, and disinformation merchants trying to profit from crisis, Io Dodds writes

In the first few hours after Russia invaded Ukraine, reports surfaced on Twitter that an American journalist had been “severely injured” or killed in a bomb blast in Kyiv.

One tweet named the journalist as Farbod Esnaashari, prefacing its news with “BREAKING” and claiming that the White House was preparing a statement.

Although Farbod Esnaashari is a real American journalist, he is not dead. Rather than reporting on foreign wars, he covers the LA Clippers basketball team for Sports Illustrated.

The news of Mr Esnaashari’s demise appears to have been a prank, just like almost identical tweets that named basketball journalist Arye Abraham and figures from various internet memes as having been killed in Ukraine.

Yet they are just small snowflakes in a blizzard of disinformation unleashed by the conflict, not all of which has such petty motives.

On TikTok and Instagram, enterprising war scammers drum up “donations” with old or faked videos thinly masked as footage from the current invasion, while on Twitter, cryptocurrency fraudsters attempt to trick supporters into donating to imaginary Ukrainian war victims.

In some ways, it is a memefied equivalent of the rolling war coverage that TV news channels pioneered in the 1990s with the Gulf and Bosnian wars, feeding people’s hunger for information with cheaply produced fakes that often spread like wildfire thanks to the social networks’ recommendation algorithms.

Yet it is also a symptom of the central role social media has played in the war itself, with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky broadcasting messages of defiance on Twitter while his government directed crowdsourced cyberattacks via the messaging app Telegram.

“In moments of high anxiety and fear and panic, when there isn’t enough information to meet people’s needs, people will accept [fake] information over no information at all,” says Abbie Richards, an independent disinformation researcher and the author of a recent report on fake TikTok war footage for the campaign group Media Matters for America.

“TiKTok was built as this singing and dancing app, and now it’s getting used for war footage. [But] the tools that built TikTok, that are the backbone of the app, are part of the misinformation problem during a crisis at the moment.”

Crypto fraudsters target Ukraine’s charity plea

In the murky world of online fraud, all roads lead to cryptocurrency, and the war in Ukraine is no exception.

On Saturday, the official Twitter account of Ukraine sent out an appeal for donations in Bitcoin, Ether and Tether, giving two unique addresses for government-controlled crypto wallets.

By Tuesday morning, donors including the crypto exchange Binance and the tech billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried had given more than £18m in crypto, according to the blockchain analysis firm Elliptic.

Waiting in the wings, however, were scammers hoping to exploit the technical complexity and irreversible nature of cryptocurrency transactions, which make it easy for a brief moment of gullibility to cause financial ruin.

ESET, a Slovakian cybersecurity firm, said it had spotted “a bevy of websites that solicit money under the guise of charitable purposes ... making emotional but nonetheless fake appeals for solidarity with the people of Ukraine”.

Meanwhile, the antivirus company Avast warned that fraudsters were posing as Ukrainian citizens on social networks such as Twitter and asking for crypto donations to help them through the chaos.

In India, the head of the ruling BJP party had his Twitter account hijacked by scammers who posted emotional appeals for Bitcoin and Ether donations, according to the Hindustan Times.

The hackers appeared eager to milk both sides of the conflict, with one tweet inviting followers to “stand with the people of Ukraine” while another asked them to “stand with the people of Russia”.

TikTok flooded with fake war footage

In August 2020, a massive stockpile of highly explosive ammonium nitrate that had been sitting in a neglected warehouse in Lebanon for six years finally ignited.

The resulting explosion tore a gigantic hole in downtown Beirut, injured about 7,000 people, and killed at least 218. One resident caught the blast on video, along with their repeated shouts of “Oh my God!”

Nineteen months later, that same audio appeared in a TikTok video – only this time it was billed as coming from Ukraine. It picked up more than 5 million views in 12 hours.

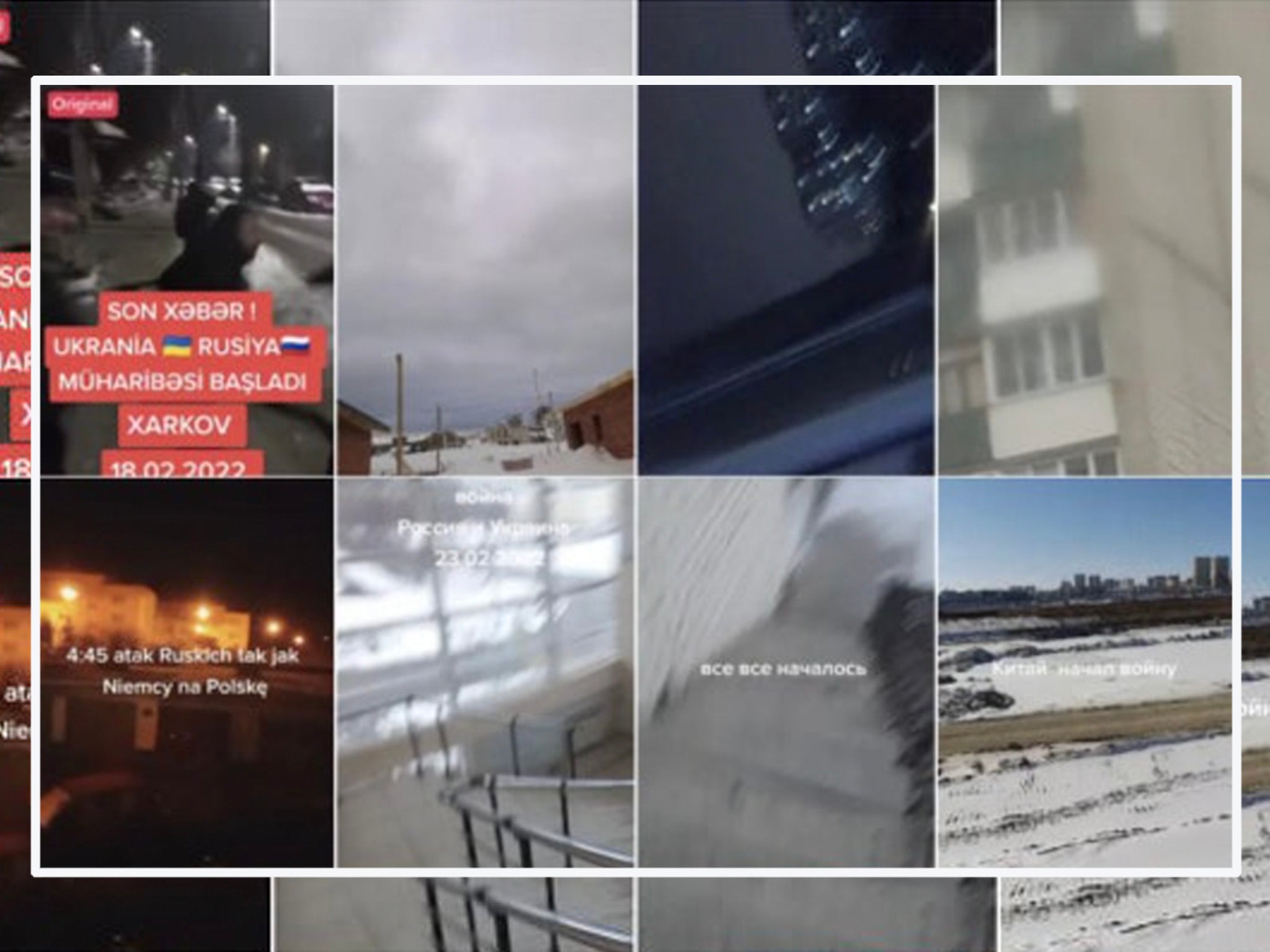

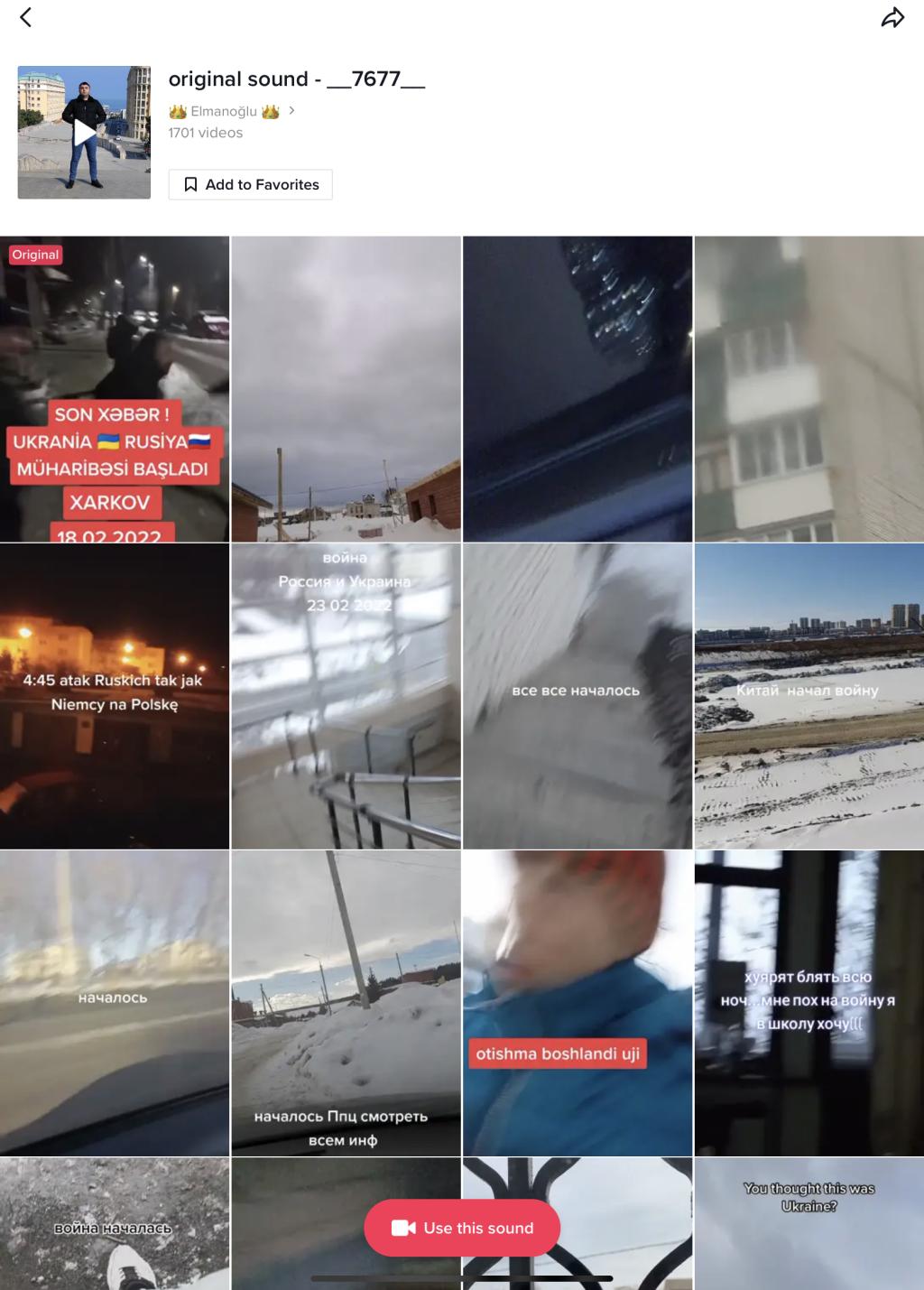

It is one of many examples catalogued by Ms Richards, whose report found that the Chinese-owned video-sharing app was “flooded” with footage purporting to show the war in Ukraine, much of it fake or reusing old video or audio. Some videos flagged by NBC News even used video-game footage in place of real clips.

“There is this sense of, like, ‘I’m watching World War Three getting streamed on TikTok’ that I see in a lot of the comments sections,” Ms Richards tells The Independent. “[People] really think that they’re watching the war unfold in front of them ... even though it’s very easy to put shaky-cam footage on top of gun noises.”

One common trick is fake live-streams, sometimes featuring looped footage, showing nondescript streets in European cities with war audio dubbed over the top. On TikTok, live-stream viewers can give hosts “gifts” worth real money, providing a simple financial motive for such scams.

At one point, Ms Richards says, she observed a supposed Ukrainian live-stream where the host’s thumb suddenly popped up in the corner of the screen and scrolled through videos, revealing that they had simply been filming another smartphone. Nevertheless, it collected numerous donations.

Other, non-live videos used TikTok’s flagship audio-swapping feature, which in peacetime lets millions of people create videos set to the same viral song or voice clip, but last week allowed more than 1,700 videos to rip off a single gunfire sample before TikTok’s moderators removed the original.

According to Ms Richards, this is just one of many ways in which TikTok’s core design helps misinformation spread. Whereas Facebook and Twitter are built around the idea of “following” specific people, TikTok’s algorithms begin showing new videos from the moment a new user opens the app.

Even if users don’t “like” anything, or follow anyone, TikTok observes how attentively they watch, rewatch and scroll in order to adjust each future recommendation. Its home feed also puts less importance on how recent content is than, say, that of Twitter.

While this rapid-fire approach has fuelled TikTok’s success, Ms Richards says it is “structurally incompatible” with the needs of anxious users searching for reliable information in a crisis.

She adds that similar scams and fake videos spread during the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, but says: “This is the most overloaded it’s been. It’s the most that it’s ever pushed the system.”

On Instagram, a similar phenomenon is unfolding whereby unrelated accounts suddenly rebrand themselves to war news pages, with networks of meme pages controlled by the same people acting in coordination to boost their profile.

The endgame, reportedly, is simply to get more followers and thereby channel as many people as possible towards fundraising pages or merchandise shops. “What I’m trying to do is get as many followers as possible by using my platform and skills,” one page admin told Input Magazine.

‘The first salvo in this war was Russian disinformation’

One social media outfit that does not need to sell merchandise is RT, formerly Russia Today, a Kremlin-controlled media outlet that spearheads Russia’s propaganda efforts in the west.

Imran Ahmed and his colleagues at the UK-based Centre for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) have been tracking RT for years, along with its sister outlets Sputnik and the Russian news agency TASS.

“We know the first salvo in this war was not missiles, it was disinformation,” Mr Ahmed, CCDH’s chief executive, tells The Independent. “That’s a war that the Russians have been fighting for a long time, creating the conditions that they think would make it easier for them to declare war on Ukraine.”

He adds: “RT is a critical part of the Russian disinformation architecture. It’s something that comes up [in our research] again and again, whether it’s climate change, anti-vax misinformation, hate, or undermining democratic values – and spreading [Donald Trump’s] ‘big lie’.”

Mr Ahmed says online platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube are crucial to RT’s impact, because its actual viewership is “tiny”. Indeed, he refers to it as a “delivery vehicle for social media optimised memes”, aiming for reach above all else.

A recent report from CCDH suggests that at least up until the eve of the war, this strategy was working. In October 2019, Facebook said it would add a warning label to posts by “state-controlled media” so users could be aware of the source of the information. However, that label does not apply when other users post a link to the same source.

Hence, CCDH studied Facebook posts linking to the top 100 most popular articles from Russian state-controlled sources, the vast majority of them from RT, posted between 24 February 2021 and 23 February this year. Out of 1,304 posts, 91 per cent carried no label because they were made by other users reposting Russian content.

Looked at another way, posts made by the outlets themselves accounted for 82 per cent of the actual likes and shares from Facebook’s users, suggesting that most of the people who interacted with these articles did see a label.

But Mr Ahmed argues that this is natural because those outlets have more followers than ordinary users, and that the research still shows Facebook’s policy is “leaky”.

And while it’s unclear whether Russian state channels make a profit, some analysts have estimated that the Kremlin generated $27m (£20m) in advertising revenue from YouTube alone between 2017 and 2018, while YouTube was estimated to make $22m of its own.

Since CCDH’s study, Facebook’s parent company Meta has cracked down. Last week it blocked Russian state media from buying ads on its services, and this week it said it would “restrict access” to RT and Sputnik across the EU “given the exceptional nature of the current situation”.

YouTube also temporarily removed RT’s ability to make money from adverts shown on its channel, citing the “extraordinary circumstances”.

‘War is just another thing they can monetise’

Aside from the Ukraine conflict, all these examples of disinformation have something in common: their success is enabled and rewarded by the features and incentives built into major social networks.

And while the likes of RT serve a clear geopolitical end, TikTok live-stream scammers and Instagram “war pages” appear simply to be finding a new application for the 21st-century truth that any sufficiently large online audience can be made to deliver a profit.

Ms Richards says some of the live-stream scammers probably have a financial motive, but others may simply want the attention. “It’s totally possible people are just doing it for the followers. That is something people want in this weird dystopia we live in.”

In either case their behaviour differs from people who are actually successful as TikTok influencers, because they aren’t creating any kind of long-term following or loyalty.

Meanwhile, the admin of one Instagram war page told Input: “What I’m trying to do is get as many people on this platform as possible. If an opportunity comes to benefit Ukraine, I can’t do that until I have the amount of eyeballs I want on there.”

Jackson Weimer, an Instagram meme creator, had a more withering view: “War is just another thing these meme accounts can monetise.”

Mr Ahmed says a similar thing about Russian state outlets on Facebook. “Most people do not use [Facebook] to spread deliberate lies that undermine human life,” he says, but argues that RT’s promotion methods are “using Facebook in the way the company intends it to be used, and allows it to be used”.

Facebook has long said that it has artificial intelligence (AI) that spots signs of misleading or divisive content and will “downrank” that content in its feed. Automated systems and user reports flag posts for its army of more than 15,000 human moderators to check.

While it does not ban “misinformation” per se, during the pandemic it has slowly banned more and more false information that it believes poses a direct threat to public safety, including vaccine misinformation and election misinformation.

TikTok has given less detail about its efforts. A spokesperson told The Independent: “We continue to closely monitor the situation, with increased resources to respond to emerging trends and remove violative content, including harmful misinformation and promotion of violence.

“We also partner with independent fact-checking organisations to further aid our efforts to help TikTok remain a safe and authentic place.”

The company also says it prevents some content, such as “spammy”, “misleading” or “unsubstantiated” videos, as well as graphic violence, from being recommended in its main algorithmic feed. Some types of videos are scanned with AI and removed automatically upon upload if they seem likely to break the rules.

Yet Ms Richards says overall TikTok’s moderation is still a “black box”, saying it has “some of the best policies out there” but often struggles to enforce them.

“How are these videos getting so big when some of them are so easily, verifiably false?” she asks. “They could be doing more to put some friction up to try and slow these videos, which just go viral overnight.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks