Did Donald Trump really build ‘the strongest economy in the history of the world'?

The US President made some audacious promises when he was elected. As Americans prepare to go to the polls four years on, Ben Chu looks into what promises Donald Trump has – and hasn’t – delivered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

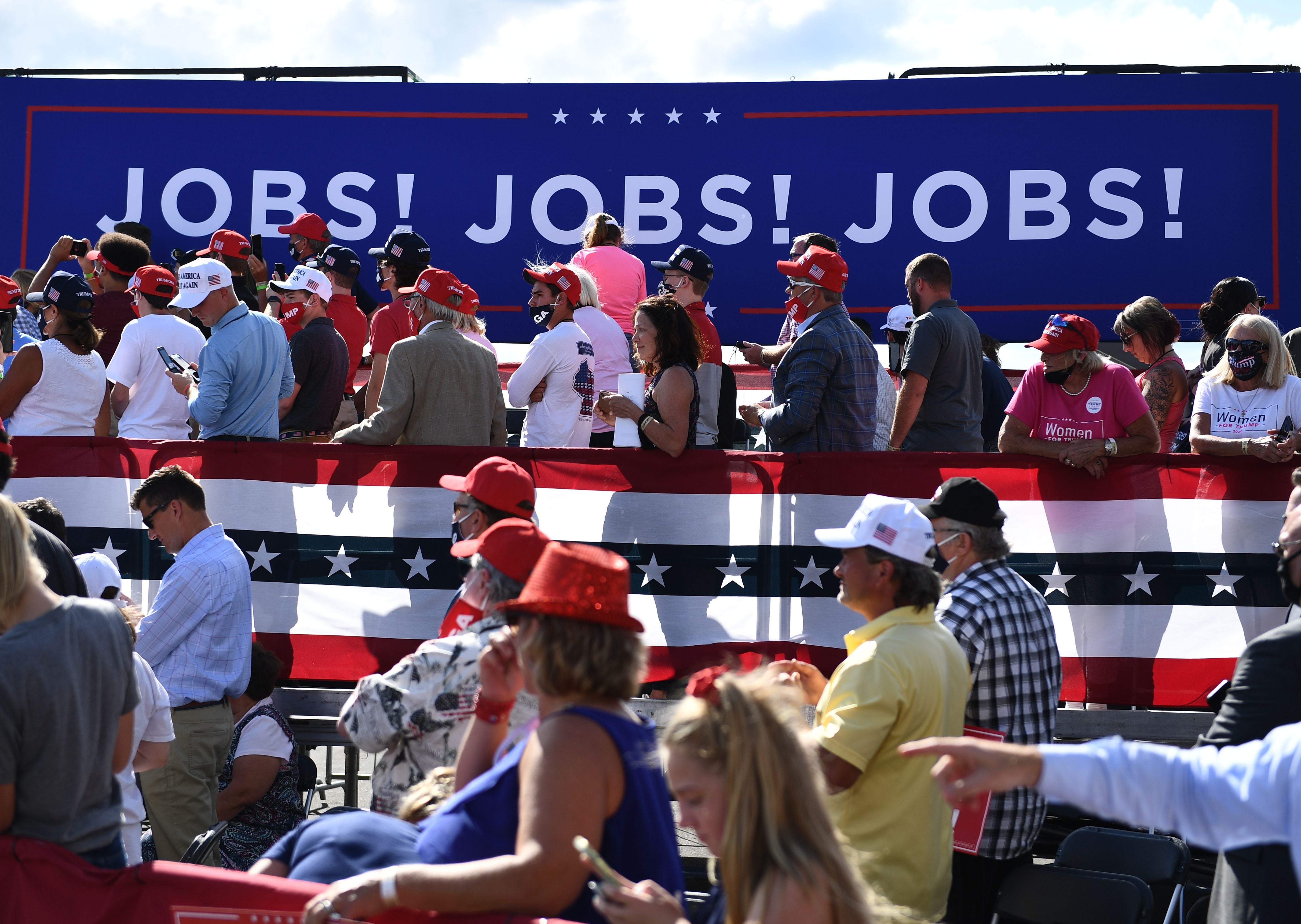

Your support makes all the difference.In August Donald Trump boasted to the Republican National Convention that, before the coronavirus pandemic, he had “built the strongest economy in the history of the world” in the three years after he became president.

The Covid hurricane has plainly upended the US economy, crushing activity by a record amount and sending joblessness soaring.

Yet, allowing for the immense hit to jobs and livelihoods over the past 10 months – which would arguably have happened whoever was in the White House – how does Trump’s overall record on the economy look? Does it measure up to the President’s high claims?

Did he deliver on his campaign promises?

What’s been the impact of his tax cuts and trade wars? What’s happened to GDP, jobs, incomes and, perhaps Trump’s most favoured metric, the stock market, since he won the 2016 election?

And, as Americans prepare to go to the polls again, how credible is Trump’s claim that, if re-elected on 3 November, he would “again build the greatest economy in history”?

GDP

One of the flashiest economic claims that Donald Trump made when he was running for president in 2016 was that it was possible to raise the growth rate of America’s gross domestic product to 4 per cent a year.

“It’s time to start thinking big once again,” he said in a speech to the New York Economic Club in September 2016.

“That’s why I believe it is time to establish a national goal of reaching 4 per cent economic growth.”

In the previous 20 years the average growth rate had been just 2.5 per cent.

The last year with annual growth above 4 per cent had been 2000, at the height of the dotcom bubble in the US.

Most economists doubted getting back to this GDP growth rate was possible. And their doubts have been vindicated.

Despite a large unfunded tax cut – the kind of policy that usually puts rocket boosters under growth – the rate of US GDP growth peaked at 3.9 per cent in the final quarter of 2017 under Trump. In the three years to 2019 the average rate of growth was 2.5 per cent – bang in line with the trend he inherited.

And this year the American economy has contracted at the fastest rate seen in any post-war presidency.

As for policy in a second term, analysts at the US credit rating agency Moody’s estimate that Joe Biden’s infrastructure spending plans would boost the US economy more than Donald Trump’s proposed tax cuts.

JOBS

“I’m going to be the greatest jobs president God ever created” was Donald Trump’s pledge when he officially announced he was running for President in June 2015.

When he took office in January 2017 there were 145 million Americans in employment. By the end of 2019 that had increased to 152 million, pointing to 6.3 million new jobs created.

That was respectable – but nothing out of the ordinary. Using the comparable period in Barack Obama’s second term (January 2013 to December 2015) the number of jobs also rose by around 7 million.

The rate of 2.1 million new jobs a year would also have left him short of his campaign pledge of creating 25 million new jobs over a decade.

Under Trump’s first three years the labour force participation rate rose slightly to 63.5 per cent. But it did little to reverse the major fall from the 67 per cent peak seen at the turn of the Millennium.

And, of course, this year the US jobs market has suffered its gravest crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Between February and April 2020 22 million jobs were lost. And the jobless rate exploded from 3.5 per cent to 14.7 per cent.

Since April some 12 million jobs have been created, bringing the jobless rate back down to 7.9 per cent. Yet many economists doubt the jobs recovery is going to be rapid on current policy.

And the deadlock in negotiations with the Democrats in Congress on extending the $2 trillion stimulus package from March is seen as creating a serious risk of more business failures and another spike in joblessness.

MANUFACTURING

“New factories will come rushing back to our shores,” promised Trump in 2016.

He claimed that his trade wars (along with pressure on US chief executives) would encourage American companies to bring back their manufacturing production from Asia and Latin America and elsewhere.

The number of manufacturing jobs in the US grew by around 500,000 under Trump’s first three years to 12.8 million in 2019. But this largely continued a rising trend that began in 2010.

There has been some evidence of US companies importing less from abroad as a result of Trump’s trade hostilities towards China.

Manufactured goods imports from 14 traditional Asian low-cost countries as a share of domestic manufacturing fell from 13 per cent in 2018 to 12 per cent in 2019, the first drop in a decade on this measure put together by the consulting firm Kearney.

Yet the Kearney analysts warn this was more attributable to a drop in imports from the traditional Asian economies rather than a significant rise in US manufacturing output.

So in that sense there is scant benefit to US ordinary workers from the trade wars.

Indeed, on the contrary, there is evidence that tariffs hurt American consumers by pushing up import costs.

On top of this researchers found that deliberately targeted retaliatory tariffs from China on US exports hit firms in Republican-voting areas the hardest.

WAGES

In 2016 Donald Trump was clear that he would not just increase jobs, but wages too.

“Every policy decision we make must pass a simple test: does it create more jobs and better wages for Americans?” he said.

He also complained that “households are making less today than they were in the year 2000”.

Median weekly earnings for full-time workers grew by around 3.6 per cent between the final quarter of 2016 and the final quarter of 2019.

This largely extended the trend that Donald Trump inherited, rather than marking an upward shift in growth.

There was a huge jump in average wages in the current crisis, though this reflected the big drop in a surge of redundancies for low-income workers and other statistical distortions rather than a genuine pay rises for Americans in the pandemic.

On median household incomes, the picture from the US census bureau did show a strong 10 per cent real-terms increase between 2016 and 2019.

And the US government’s $2.2 trillion stimulus package has supported many incomes so far this year – indeed around three quarters of unemployed Americans according to one estimate earned less than the new $600 a week jobless benefit that was introduced.

But this aid is lapsing and if it is not replaced there is likely to be a major negative impact on Americans’ living standards.

It’s worth noting that Trump threatened to call off negotiations with Congress on 7 October over extending the assistance to households not because he saw them as insufficiently generous but because he said the Congress Democrats’ proposals would help “cities and states” that tend to vote Democrat.

TAX CUTS

In 2017 Donald Trump and his Republican party cut personal taxes.

“Our focus is on helping the folks who work in the mailrooms and the machine shops of America,” claimed the President.

“The plumbers, the carpenters, the cops, the teachers, the truck drivers, the pipe-fitters, the people that like me best.”

Yet more than 60 per cent of the tax savings went to people in the top fifth of the income ladder, according to the independent Tax Policy Centre.

The top 1 per cent received 20 per cent of the benefits.

The typical justification for income tax cuts is that they encourage entrepreneurship and boost overall growth, which ultimately means more tax is collected. But, as we have seen, there has been little evidence of any uplift in GDP growth in recent years.

Trump also cut corporate taxes significantly in 2017, saying that this would encourage business investment. But despite the boost to companies’ cash flows, investment by firms has fallen rather than increased.

STOCK MARKET

For much of the past four years Trump’s twitter feed while he has been in office has been dominated by boasts about the performance of the stock market.

Share prices, as represented by the index of America’s largest 500 companies, did rise sharply from the moment he was elected president in November 2016. Over the next three and a half years it shot up by 55 per cent.

But shares also fell at a faster rate than the Wall Street Crash in February this year as the pandemic terrified investors and traders. At one stage in March shares were just 3 per cent higher than when Trump won the 2016 election.

Yet the comeback since then has been stunning – with shares recovering all the losses of the crash and hitting a new record high in September.

However, many analysts think the decision of the US central bank to effectively promise unlimited money printing to support the economy at the nadir of the slump in March has as much to do with the stunning recovery of share prices as optimism about Trump’s economic management.

Economists also point out that the stock market is not, despite what the president claims, some kind of barometer of the underlying performance of the US economy and gauge of national prosperity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments