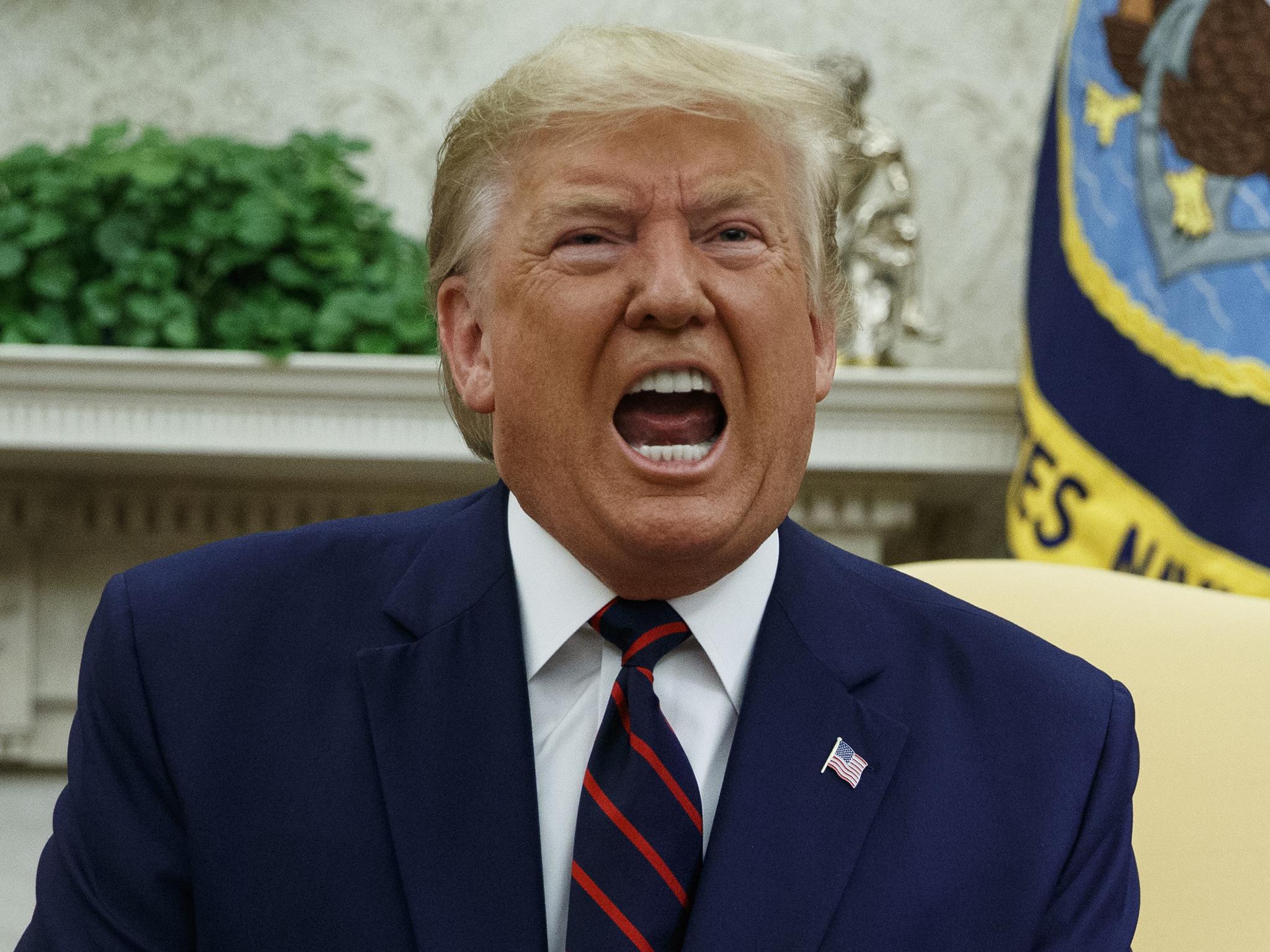

From ‘hell’ to ‘lynching,’ Trump presides over a coarsening of political language

President’s disregard for traditional standards of civil discourse is well recorded, now Philip Rucker and Ashley Parker look at the effects his behaviour is having on wider political sphere

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Donald Trump unleashed a gusher of foul language, referring to himself as a “son of a bitch,” claiming that Joe Biden was a good vice president only because “he understood how to kiss Barack Obama’s ass,” and saying “hell” 18 times – and that was all in a single campaign rally.

At another rally the following night, Mr Trump denigrated Mr Biden’s son, Hunter, for his struggles with substance abuse and called him a “loser,” while also declaring that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi “hates the United States of America.”

This week, Mr Trump declared that the House impeachment inquiry was a “lynching” – equating his political troubles with the systematic murders of African Americans by racist white mobs.

The US leader, who long ago busted traditional standards for civil discourse and presidential behaviour, has taken his harsh rhetoric and divisive tactics to a new level since impeachment proceedings began a month ago – and he appears to be pulling a significant part of the country along with him.

A number of Republicans, for example, defended Mr Trump’s lynching comparison, pointing to past uses of the metaphor by Mr Biden and other Democrats. The Trump campaign is selling “Where’s Hunter?” T-shirts for $25 (£19), while the House Republicans’ campaign arm mocked a Democratic congressman and his wife for seeking marital counselling.

At a conference for a pro-Trump group at the president’s Miami golf resort, an incendiary animated video was shown depicting Mr Trump on a gun rampage inside a church, murdering members of the media, political rivals and a “Black Lives Matter” protester.

There is a long history of sometimes rough language and deeply personal attacks in American politics, from the heated rhetoric surrounding the Clinton impeachment to campaigns that stoked racial division. And the shifting tone isn’t limited to the president and his backers: At the same Minneapolis rally this month where the president went on a swearing spree, anti-Trump protesters chanted profane and angry cheers – “Kill a cop, save a life!” – while clashing violently with his supporters.

But the 45th president appears to be presiding over a particularly coarse period of American politics – inviting the rest of the country to splash around in the muck as he upends long-held norms of acceptable behaviour.

“We’re in a unique place in modern American history,” said Joshua DuBois, who served in the Obama White House as a faith adviser to the president. “We have for decades had presidents who’ve tried, oftentimes imperfectly, to appeal to our better angels.”

Mr Trump, said Mr DuBois, “has said let’s bring out the nastiness, the division, the bitterness, and let’s use that as a mobilising force and a rallying cry.”

The White House declined to comment, but the president’s conservative defenders say Mr Trump bears little responsibility for any perceived loss of civility.

Some evangelicals, for example, have objected to Mr Trump’s occasional use of the epithet “goddamn,” which many Christians view as blasphemy. Jerry Falwell Jr, president of the evangelical Liberty University, said that he was unaware of those incidents, however, and that Mr Trump’s other profanities do not offend him, though it’s not the way Mr Falwell himself speaks in public.

“I think it’s part of his personality,” Mr Falwell said. “There’s nothing un-Christian about saying ‘damn’ or ‘hell.’ ”

Although some of Mr Trump’s rhetoric would likely violate the school’s code of conduct barring “offensive or crude language directed at individuals,” Mr Falwell emphasised that the rules only apply to students on campus.

“So if somebody leaves Liberty University and decides to be president, we’re not going to say they’re bad because they start cussing,” he said.

Others are less forgiving and say it’s about far more than swear words. Many of Mr Trump’s critics say his racist and racially charged language is particularly damaging.

In July, Mr Trump tweeted that four minority congresswomen – all US citizens – should “go back” to the “crime infested places from which they came.” At his profanity-laden rally earlier this month in Minneapolis, the president attacked Representative Ilhan Omar - the Somali immigrant who represents the city – as “an America-hating socialist” and also attacked the state’s population of Somali refugees, prompting “boos” from the crowd.

“We’ve got a president who is out of control, who says horrible things all the time about minorities, about marginalised populations, about vulnerable populations, and then it is amplified to all these allies the president has made,” said Heidi Beirich, head of the Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Centre, which has tracked a 30 percent increase in the number of hate groups from 2015 to 2018. “Your garden variety racist or anti-Semite sees this stuff and feels justified for his or her beliefs, and so it’s literally soaking all the way down the culture, from the top down.”

Michael Waldman, who served as chief speechwriter for president Bill Clinton during impeachment and is now president of the Brennan Centre for Justice at New York University School of Law, said that Mr Trump is smashing “the gravity and majesty of the office” and that “his coarseness and demagoguery are undermining his own use of the bully pulpit.”

But for Mr Trump, the inflammatory and provocative statements are often intentional. At the Minneapolis rally, he underscored this truth when he gushed to his supporters: “Isn’t it much better when I go off script? Isn’t that better?”

One of his major targets of late is Hunter Biden, who has come under scrutiny for accepting a paid position on the board of a Ukrainian energy company while his father was vice president. At a campaign rally in Dallas last week, Mr Trump mocked Mr Biden’s struggles with drug use and said he was “thrown out of the Navy like a dog” – a reference to Mr Biden’s discharge from the Navy Reserve after testing positive for cocaine.

[Republicans] were the ones that made the argument that politics matters in part because it helped set the tone for a nation. Donald Trump is dragging that down

The president has also been relentless in his personal assaults on Ms Pelosi, who dubbed Mr Trump “a pottymouth” after his expletive-filled Minneapolis rally. Following a fraught meeting at the White House last week, which ended with some Democrats walking out, Ms Pelosi described Mr Trump as having a “meltdown” – prompting Mr Trump to fire back on Twitter.

“Nancy Pelosi needs help fast!” he tweeted. “There is either something wrong with her ‘upstairs,’ or she just plain doesn’t like our great Country. She had a total meltdown in the White House today.”

Mr Trump has also moved boundaries in more risque directions. At one point during his rally in Minneapolis, the president performed a mock conversation between Lisa Page and Peter Strzok, two senior FBI employees who exchanged anti-Trump text messages while they were having an affair.

“’I love you, Peter.’ ‘I love you too, Lisa. Lisa, Lisa, oh God, I love you, Lisa,’” Mr Trump said, mimicking imagined dialogue between the two that crescendoed into breathless panting.

Ralph Reed, a conservative Christian activist who is working on a book, For God and Country, about how evangelicals are morally correct in supporting Mr Trump and his policies, said that the current moment is not alarming when viewed through the long arc of American history.

“This is not a crisis on the level of Watergate, the Civil War or the Vietnam War,” Mr Reed said. “It’s troubling but it’s not exactly a red light on the dashboard of danger to civil order. We’ve seen much worse and we’ve lived through much worse.”

Peter Wehner, a Trump critic who served in the past three Republican administrations and is a visiting professor at Duke University, said one irony of Mr Trump’s behavior is that, for years, conservatives had anointed themselves the unofficial gatekeepers of public morality.

“Once upon a time it was Republicans and social conservatives who spoke most forcefully about the state and condition of our culture, including our political and civic culture,” Mr Wehner said. “They were the ones that made the argument that politics matters in part because it helped set the tone for a nation. Donald Trump is dragging that down.”

Critics on both sides point to what they see as a general debasement of standards by the other.

In Minneapolis, an anti-Trump protester spotted a lone man in a blue parka as he left the rally by himself and shouted: “There’s a Nazi over here!”

A small group of protesters surrounded the man and pulled his ball cap off his head. As he frantically tried to fend them off, a young man walked up and slapped him across the face. The rally goer scuffled with the protesters and repeatedly tried to run away as they chased him, throwing punches.

Many of the 2020 Democratic hopefuls have also begun using foul language, with Beto O’Rourke, a former congressman from El Paso, often leading the charge in what appears to be an effort to convey passion and authenticity. Representative Rashida Tlaib, one of the congresswomen attacked by Mr Trump, generated controversy earlier this year when she urged her supporters to “impeach the motherf***er,” referencing Mr Trump.

Meanwhile, at a Trump rally last week in Texas, one of his allies seemed to attempt to channel the president himself. Texas Republican lieutenant governor Dan Patrick, an honorary chairman of Mr Trump’s campaign, warmed up the crowd by mocking “the rabble” on the Democratic presidential debate stage a couple nights earlier.

“The progressive left, they are not our opponents – they are our enemy,” Mr Patrick said.

He went on to malign Mr O’Rourke as “a moron” and to coin his own nickname for House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff, who is leading the impeachment inquiry: “Adam bull-Schiff.”

“It’s all bull-Schiff, all the time,” Mr Patrick said. “I was careful with my words. My pastor’s watching.”

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments