How Truman Capote betrayed his ‘swans’: The real-life high society saga behind Feud’s season 2

A new season of the TV show “Feud” will look into the novelist’s life before and after the publication of a short story that scandalized high society -- and Capote’s friends. Clémence Michallon reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

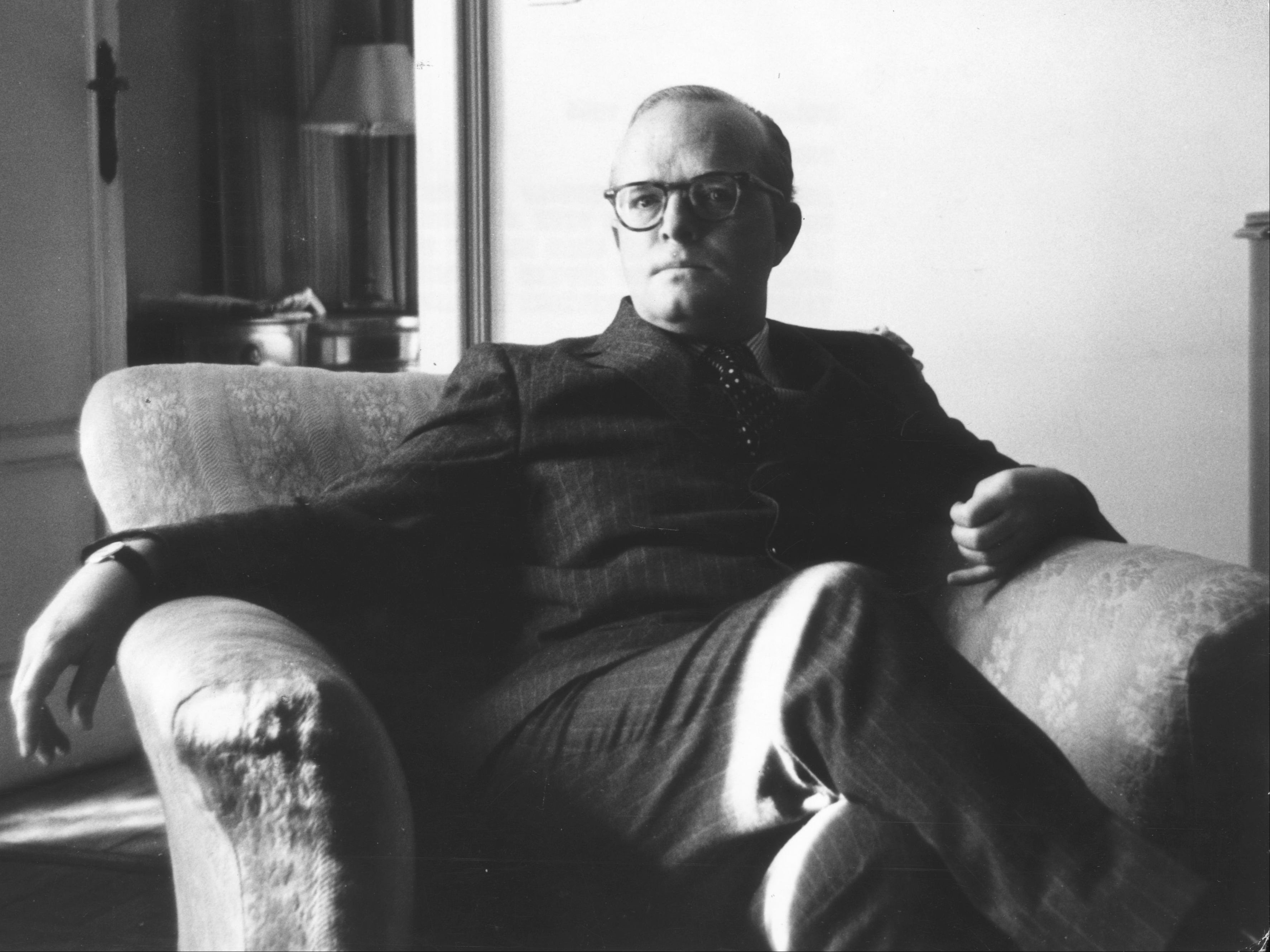

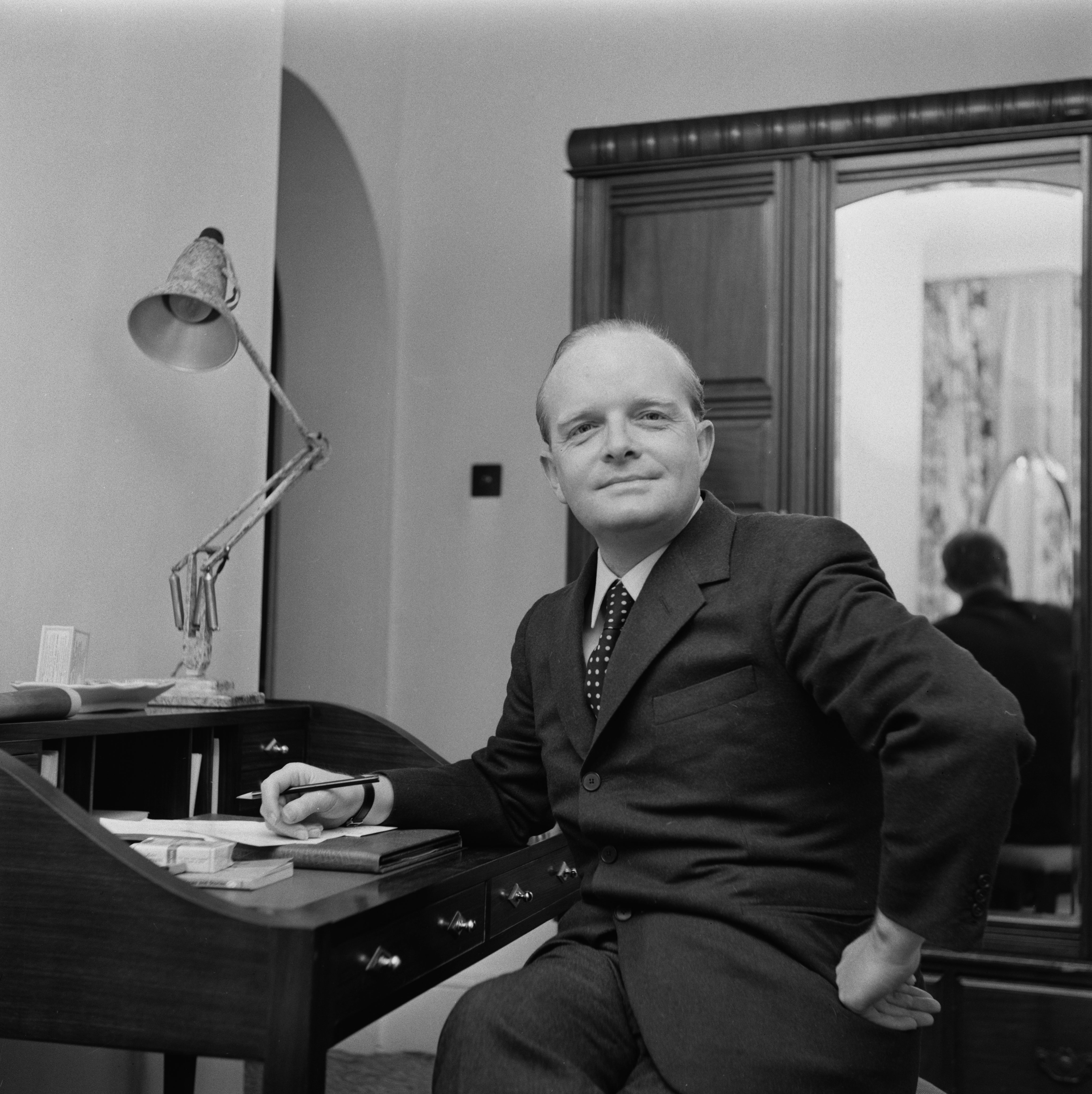

Your support makes all the difference.Truman Capote wanted to make waves. Not that he needed to make waves, necessarily: By the time his short story La Côte Basque, 1965 ran in Esquire in November 1975, Capote was already a literary superstar. In Cold Blood had been out for a decade; Breakfast at Tiffany’s for 17 years. Capote had two Edgar Awards. He owned an apartment with sprawling views on the U.N. Plaza – at the time “the place to live in Manhattan”, set designer Oliver Smith later told Vanity Fair – and a custom-built house in Sagaponack, Southampton. He was successful by more than one measure. But he hadn’t had a true professional win since his 1967 Emmy for A Christmas Memory, the adaptation of his 1956 short story of the same name. And the 1968 TV adaptation of the film noir Laura, for which he had written the teleplay, had just flopped.

Thus, Answered Prayers, a novel Capote had been working on since 1958, was brought back to the center of his life. Esquire published an excerpt as a short story titled La Côte Basque, 1965 in 1975. While Answered Prayers was never published in its finished form (the full manuscript was never located, and it’s unclear whether it was ever completed), much has been made of La Côte Basque, 1965. The short story was once described as “an atomic bomb that Truman Capote built all by himself” by Vanity Fair. It has come to mark one of the final turning points in Capote’s life – the beginning of a period that saw him struggle more acutely with drug and alcohol abuse, to the detriment of his writing and social life. (He died from liver disease complicated by phlebitis and multiple drug intoxication in 1984.)

This period of Capote’s life will be explored in the next season of the TV series Feud, co-created by Ryan Murphy. (The first season, Bette and Joan, was a dramatization of the rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford.) Capote’s Women is expected to begin filming in New York this autumn, according to Deadline. It will star Naomi Watts as Babe Paley, once a close friend of Capote’s, and one of the multiple people who were part of the La Côte Basque, 1965 fallout. The show is an adaptation of the 2021 book Capote’s Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era, in which biographer Laurence Leamer “reveals the complex web of relationships and scandalous true stories behind [Answered Prayers]– the dark secrets, tragic glamour, and Capote’s ultimate betrayal of the group of female friends he called his ‘swans.’”

So, how does a short story, of all things, court scandal? Well, it must be written by a jet-setting writer like Capote, whose social circle included the likes of Barbara “Babe” Paley (married to the CBS founder William S Paley) and Gloria Vanderbilt. That writer must also decide to include in his short story a less than flattering portrayal of New York’s upper crust. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly of all, the short story must awaken or reveal some memories, anecdotes, and theories that these high-ranking friends would rather not make it to the public eye.

La Côte Basque, 1965 ticks all of these boxes. Capote, per Vanity Fair, wanted Answered Prayers (of which La Côte Basque, 1965 was to be the fifth chapter) to “do to America what Proust did to France.” He once described it to People magazine, per Electric Literature, using the vocabulary of weaponry: “There’s the handle, the trigger, the barrel, and, finally, the bullet. And when that bullet is fired from the gun, it’s going to come out with a speed and power like you’ve never seen — wham!”

By Esquire’s own description, La Côte Basque, 1965 “became famous for the scandals it brought” and “contains insensitive descriptions of beauty and body standards.” The story’s two main characters, Lady Ina Coolbirth, and Jonesy, sit down for a long, boozy lunch at a now-defunct New York restaurant once called Côte Basque (eulogized at the time of its closing in 2004 by The New York Times as having been a “high-society temple of French cuisine”).

“Let’s have something that takes forever. So that we can get drunk and disorderly,” says Lady Coolbirth early in the story. She and her lunch companion embark on a meal of soufflé Furstenberg – “a froth of cheese and spinach into which an assortment of poached eggs has been sunk strategically” – and Roederer’s Cristal champagne – “a chilled fire of such prickly dryness that, swallowed, seems not to have been swallowed at all, but instead to have turned to vapors on the tongue and burned there to one damp sweet ash.”

Lady Coolbirth and Jonesy eat, drink, and talk. Spotted in the dining room is Gloria Vanderbilt, who, in Capote’s fictional rendition, fails to recognize her first husband, Pat DiCicco. “Oh, darling,” her friend comforts her once the fictional Vanderbilt realizes her mistake. “Let’s not brood. After all, you haven’t seen him in almost twenty years.” The real-life Vanderbilt reportedly did not take well to the portrayal: “I think Truman really hurt my mother,” her son Anderson Cooper told Vanity Fair in 2012.

Also referenced by name is Jackie Kennedy, sitting down for lunch with her sister, “their heads inclining toward each other in whispering Bouvier conspiracy.” Capote did use some fictional names in the short story: Ina Coolbirth and Jonesy discuss at length a woman named Ann Hopkins, whom they claim shot dead her husband David Hopkins. Ann Hopkins, we learn, claimed she shot him accidentally, because she believed he was an intruder. Lady Coolbirth, however, claims Ann Hopkins knew what she was doing and “got away with cold-blooded murder.”

The passage is reminiscent of the real-life case of Ann Woodward and her husband William Woodward Jr, who was shot dead in 1955 by his wife at the couple’s home in Oyster Bay, New York. Ann Woodward always said she had mistaken him for a burglar; she was never charged and died by suicide in 1975. Per Esquire, “Ann Hopkins, in Capote’s writing, was a veiled version of Woodward.”

Another character in the short story is one Sidney Dillon, a character believed to be – as mentioned by the Chicago Tribune – based on William S Paley, the CBS founder whose second wife, Babe Paley, was a close friend of Capote’s. Sidney Dillon is depicted in the short story as cheating on his wife with the governor’s wife, whose menstrual blood he later finds on the sheets. Babe Paley, according to Vanity Fair, was “horrified and heartbroken” by the story and never spoke to Capote again. “Babe was appalled by La Côte Basque,” the late British art historian, Picasso biographer, and Vanity Fair contributing editor told the magazine. “People used to talk about Bill as a philanderer, but his affairs weren’t the talk of the town until Truman’s story came out.” Babe Paley died in 1978 of lung cancer. William S Paley died in 1990 after becoming critically ill.

La Côte Basque, 1965 ends in “an atmosphere of luxurious exhaustion, like a ripened, shedding rose, while all that waited outside was the failing New York afternoon.” Esquire published three other excerpts from Answered Prayers: the first, Mojave, ran in June 1975, a few months before La Côte Basque, 1965. The other two, Unspoiled Monsters and Kate McCloud, ran in May 1976 and December 1976 respectively. Answered Prayers was published in an unfinished form in 1987, after Capote’s death.

“Answered Prayers’ reveals the seduction of Capote the artist by Capote the socialite. He had become a sacred monster himself,” wrote then-Vanity Fair editor-in-chief Tina Brown in a review of the book for The New York Times. “Even as he burned his bridges he still fantasized the rich, still retained the outsider’s thrill at being on the inside track.”

Capote, according to Brown, was surprised when his social circle became alienated by his writing. “What did they expect?” he’s said to have mused. “’I’m a writer, and I use everything. Did all those people think I was there just to entertain them?”