The big surprise in Little Italy

The latest New York census found that not a single Italian lives in the home of Mafia legend. David Usborne walks its 'mean' streets

It is breakfast time outside the Grotta Azzurra on the corner of Mulberry and Broome. At an outside table Nick Bari nurses a smouldering cigar and reads the paper. All in black, Camile Garibaldi, the restaurant's manager, chats on the pavement with a friend before returning inside to see to customers.

All is well this morning in Little Italy. Or so it would seem. Up and down Mulberry Street, the main thoroughfare where the tourists roam and the restaurants hawk their focaccias and linguine con le vongoles, banners on lamp-posts welcome first-timers to "Historic Little Italy". If you look down you will see that the posts have been freshly painted in red, white and green.

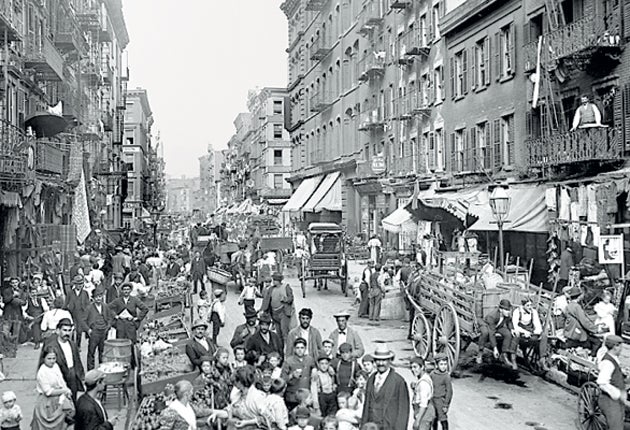

While small enclaves of ethnic identity pepper the street-maps of New York, few generate more affection than Little Italy. Its history as home to thousands of Italian immigrant families and – lest we forget – as stamping ground for the city's growling Mafia goons, still means it features high on the itineraries of Manhattan visitors.

But these days the neighbourhood finds itself in uncharacteristically defensive mode.

First came word from the US Census Bureau that Little Italy was, well, barely Italian any more, which prompted a "Little Italy, Littler" headline in the New York Times. That was followed by a bid by some non-Italian boutique owners to have the San Gennaro festival that crowds Mulberry Street each September curtailed on the grounds that it was hurting their businesses.

The census data released earlier this year included one particularly startling fact. Of the 8,600 residents interviewed in the two-dozen-square block area of Lower Manhattan that might still be deemed Little Italy – determining its borders is another area of contention – not one was actually born in Italy. And descendants of immigrants from Italy (Italian-Americans) made up only 5 per cent of the area's population.

It is a stark demographic evaporation which has been going on for decades. In 2000, the US Census Bureau found 44 Italian-born people in the neighbourhood and a 6 per cent share for Italian-Americans. Back in 1950, there were 10,000 New Yorkers residing in the area and nearly half were considered Italian-Americans.

"I wasn't shocked and I don't think anyone else should have been," notes Robert Alleva, 58, who runs the venerable Alleva Dairy on Mulberry and Grand, which was first opened by his great grandfather, an immigrant from a village close to Naples, back in 1892. His white-tiled shop is heavy with the soft and seductive smell of fresh mozzarella – it is the oldest maker of the cheese in America – as well as giant salamis hung on hooks and other Italian fare.

"It's really all commercial now," Mr Alleva, in his white dairyman's coat, explains. "As far as Italian immigrants living here goes, that is all history. It's too expensive to live here." Members of his own family, who in the early days set up home directly above the shop, were among the first to broaden the Italian Diaspora, with some moving to Long Island as far back as the Twenties. Today, Robert, whose son works in the shop at weekends, lives with his family in Queens.

With Chinatown crowding in from the south and east, the geography of Little Italy has also been shrinking. Last year, the National Parks Service designated Chinatown and Little Italy in Manhattan as a historic district, without bothering to distinguish between them.

But the encroachments have not been as dramatic as some people think, says Mr Alleva. "Maybe we have lost a block on that side and another on the other," he says, pointing in different directions down Grand, "but for the rest it's pretty much the same as 30 years ago."

With his newspaper and coffee, Nick Bari, who recently took over Benito One, a modest looking but highly rated restaurant on Mulberry, also says there is no concealing the changes. It is not just the Italian-Americans who have gone but also most of the mom-and-pop butchers and grocery shops that used to feed them, and many of the old social hang-outs. "Real estate is too expensive," he says bluntly.

Next to Benito One is a shop with a blue awning which says Aqua Star Pet Shop in Chinese characters. Nowadays, anyone trying to capture the Italian feel of Mulberry Street with their camera will have a difficult time editing out the Chinese intrusions. But no one should say that Little Italy is endangered, Mr Bari insists: "There will always be something down here. The Italian theme will be here for many years to come."

Partly it is the tourists who promise to keep it alive. It does not escape Mr Bari or Mr Alleva that it is partly the fascination with the mythology of the Mafia which keeps them coming, even though it is years since Vincente Gigante, the former head of the Genovese family, took to wandering the streets here in a dressing gown as part of a ruse to persuade prosecutors he had lost his sanity. The old Ravenite Social Club on Mulberry, a former favourite of the Gambino family, is now a handbag and shoe shop.

Mr Alleva, who sells an increasingly large proportion of his parmiaggiano, pepperoni and olives via mail order and his website, chuckles and shakes his head over how the mob legends help draw the crowds. "They expect to come down here and see a guy sitting on a bench with a machine-gun," he says.

But, as Mr Garibaldi at the Grotta Azzurra points out, the neighbourhood also fills at weekends and especially during the San Gennaro festival with Italian-Americans coming back in from the suburbs to get back in touch with the old neighbourhood and eat food like grandma made. "Little Italy will never die," he insists. "When the feast is on every Italian-American from all the five boroughs (of New York City) comes to Little Italy."

The restaurant manager, meanwhile, snorts scornfully when reminded of the recent squabble over curtailing the festival. Shop owners on the north edge of Little Italy had asked the local neighbourhood committee to limit the San Gennaro activities to fewer blocks along Mulberry, complaining that the daily (and nightly) ruckus was keeping shoppers away. In the end, the feast was allowed to stay just the way it has for decades.

"Every year they say they are going to cut it back, but it will never happen," Mr Garibaldi asserts, glancing at the few breakfast customers in his white-tablecloth dining room. "Just because there are all those new boutique stores up there, that doesn't mean the feast has to end. They can close for 11 days if they want. And if they don't like the smell of sausage and pepper well that's their problem."

But even diehards like Mr Garibaldi – who arrived here with his parents from Sicily when he was eight years old – cannot deny that Little Italy is not quite what it used to be. He was raised in Little Italy but now lives on the Upper East Side, principally, he says, because if he lived above the shop his work day would never end.

He has the simplest explanation for why Little Italy, with its ever spiralling rents and tiny apartments, no longer belongs to Italians. "We all came from southern Italy. We like to have a lot of kids." And kids mean suburbs.

Little Italy in the movies...

The Godfather, 1972

Mobster movie buffs will recognise much of Manhattan's Little Italy, even if they have never visited in person. In the classic gangster film The Godfather, the 200-year-old Old St Patrick's Cathedral provides a dramatic setting for the scene when Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) is awarded the Order of St Sebastian the Martyr, and in The Godfather Part III, Elizabeth Street hosts the fateful festival during which Joey Zasa (Joe Mantegna) is gunned down.

Mean Streets, 1973

Struggles with loan sharks, loyalty and religious guilt are all explored in this Martin Scorsese drama, set on the "mean streets" of Little Italy. St Patrick's Old Cathedral stars once again, but this time it's the graveyard which provides the backdrop for a heart-to-heart between the protagonists Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro) and Charlie (Harvey Keitel). The area struck a chord with Scorsese, who returned to the church again when filming his 2002 epic, Gangs of New York.

Donnie Brasco, 1997

Al Pacino revisited Little Italy to play Benjamin "Lefty" Ruggiero in one of the most famous true-life tales of police infiltration into mob life told by Hollywood. The Mulberry Street Bar provides a meeting place for Pacino's character and the undercover cop "Joe" Pistone, otherwise known as Donnie Brasco (Johnny Depp). Once frequented by Frank Sinatra, the watering hole was also featured in The Sopranos.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks