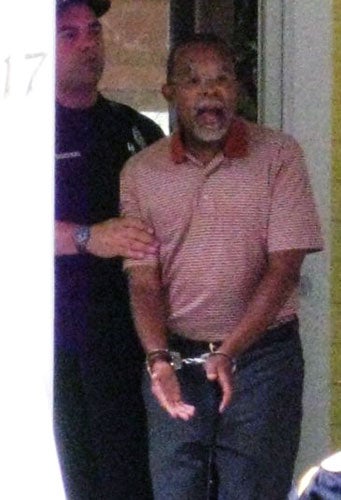

The arrest that divided America

When police attended a call-out to a burglary, they ended up detaining a black professor at his own home – and re-igniting a heated debate on racial profiling

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Imagine, if you will, a professor at Cambridge, one of the most learned and best known scholars of his generation, being arrested by police after forcing the door of his house when the front lock jammed. Impossible, you will say. But that is what happened. Except the Cambridge in question is not in East Anglia, but a town in Massachusetts that is home to the British university's American equivalent, Harvard, and that Henry Louis 'Skip' Gates, the professor who lived at this most pleasant abode, is black.

Every now and then, a small incident crystalises a great issue, and the Gates affair is one of them. The issue is racial profiling, the pernicious habit of police or other authorities to use race as a basis for suspicion of a crime. It is to be found in many countries, but nowhere is it more sensitive or controversial than in the US, where racism is the original sin.

Mr Gates had returned from an academic trip to China last week but could not get into his house. With his driver, he forced the door and called the company that managed the house to complain. Unfortunately, someone had seen "two black men with backpacks on the porch", apparently trying to force entry, and called the police.

Of what happened next, accounts differ. Professor Gates maintains he showed the officer who arrived his driving licence with his address, and his Harvard University ID. The police, however, say he became angry, shouting and making accusations of racism, saying at one point: "You don't know who you're messing with." Whereupon he was arrested for disorderly conduct and taken to the Cambridge police station.

And indeed, the police did not know who they were messing with. The 58-year-old Mr Gates is arguably the pre-eminent contemporary scholar of African-American affairs, a tenured Harvard professor, an author of 10 books who has hosted and narrated two public television series on black America, and who in 1997 was named by Time magazine as one of the 25 most influential Americans. He also happens to be a good friend of the most celebrated black man in the world, the 44th President of the United States.

Thus it was that this spot of local bother in a Boston suburb cropped up at a White House press conference on Wednesday night, otherwise made over to health care, on which Barack Obama held forth for the best part of an hour, with numbing expertise. Then, just as things were winding down, he was abruptly asked what he made of the Gates arrest.

Initially, the President turned the question upon himself, with a joke – what might happen to him if he were seen trying to get through his own front door when the lock had jammed. "I guess this [the White House] is my home now," he mused, "so it probably wouldn't happen. But let's say my old house in Chicago. Here I'd get shot." Maybe Obama was expecting to be asked about the incident, maybe not. But that he had followed it closely was evident at the conference, as he rattled through the events of the previous Thursday evening. "The police are doing what they should. There's a call and they go investigate. What happens? My understanding is that Professor Gates then shows his ID to prove that this is his house, and at that point he gets arrested for disorderly conduct."

That alone would have been unusual enough comment from a US president on what could yet become a lawsuit – on an incident about which, by his own admission, he had not seen all the facts. But Obama was not finished. He did not know whether race had been a factor, but three things were clear. First, "any of us would be pretty angry" in such circumstances. Second, the Cambridge police acted "stupidly" in arresting somebody when there was already proof that they were in their own home. And thirdly, the President declared, "separate and apart from this incident, there is a long history in this country of African-Americans and Latinos being stopped by police disproportionately. That's just a fact." Later, the White House issued a clarification, emphasising that the President "was not calling the officer stupid". But the impact of his words was plain enough.

For on the President's last point, there can be no argument. Officially, racial profiling should not happen in the US. Formally, or informally, it happens all the time. Mr Obama himself could indeed have been caught up in a similar incident, as a law professor, an Illinois state legislator, or even a full-blown US senator, when he lived in the affluent Kenwood and Hyde Park neighbourhoods on Chicago's largely black south side.

Nor is Mr Gates the first high-profile black to be so embarrassed. In Los Angeles, home of racially charged cause célèbres ranging from Rodney King to OJ Simpson, the flamboyant Johnnie Cochran, at his peak arguably the most famous American lawyer of any colour, was once stopped by police in his Rolls-Royce while his children were in the back. This was despite the fact that his car bore vanity licence plates with his initials and the fact that at the time, he was leading an investigation of police abuse by the local district attorney's office.

But thousands, maybe tens of thousands, of black and minority Americans are less fortunate, subjected to similar indignities unchronicled by any newspaper or TV report, unmentioned at a White House news conference.

Consciously or unconsciously, racial profiling occurs all the time. Consciously, as when it emerged a few years ago that Maryland state police were stopping motorists partly on the basis of a "drug courier profile" set up in the early 1990s. A subsequent study found that blacks accounted for only 15 per cent of speeding motorists but almost three-quarters of those who were stopped and searched.

Then there is the profiling in which we all indulge. Who doesn't feel a tad uneasy near a group of young black men in a deserted public place – even a certain Jesse Jackson, a spokesman for black America for more than a generation? "I hate to admit it," Jackson once said, "But I have reached a stage in my life that if I am walking down a dark street late at night and I see that the person behind me is white, I subconsciously feel relieved."

The instinctive underlying assumption about Johnnie Cochran was that a black man simply couldn't have made enough money by honest means to be driving a Rolls. Even though the police in Cambridge, Massachusetts, deny it, there may have lurked the automatic, subconscious view that a black man couldn't possibly afford to live in such a house. Ergo, he had broken into it.

According to Amnesty International, 26 of the 50 US states have no ban on racial profiling and all but four permit profiling based on religion or religious appearance. At a federal level the practice is taboo – which is why elderly white women find themselves singled out for screening at airport security at the same rate as young men like Hussein or Mohammed. But try telling that to Muslim immigrants harassed in the wake of 9/11.

It seeps into the most everyday moments in life. These include, as Reginald Shuford, the top racial profiling litigator at the American Civil Liberties Union has put it, "shopping while black or brown (being followed in a store or ignored altogether), hailing a cab while black or brown, dining while black or brown (tip automatically added to the bill of a black patron, under the theory that blacks are poor tippers), riding (as in a bike, in a particular neighbourhood) while black or brown, running (as in jogging or exercising) while black or brown."

So widespread and pervasive is the phenomenon, he argues, that "another phrase has been coined: breathing while black or brown." Such is the eternal reality of race in America, even when a black man has been elected to the highest office in the land.

Theoretically, the Cambridge case is closed. Prosecutors have dropped the disorderly conduct charge. The city authorities have stated that the arrest was "regrettable and unfortunate". Even so, this may not be the end of the matter. Professor Gates is holding out for a personal apology from Sgt James Crowley, who arrested him – a mea culpa that is most unlikely to be forthcoming. The police union has pledged its "full and unqualified support" to the officer, while Sgt Crowley himself insists he acted strictly by the book.

What was regrettable, he said, was that the President of the United States had "waded into what should be a local issue" of which, "as he himself said, he doesn't know all the facts".

For and against: How the US responded

"Barack Obama being President has meant absolutely nothing to white law enforcement officers. Zero... Imagine a distinguished white professor at Harvard, walking around with a cane, going into his own house, being harassed by the police. It would never happen." Earl Graves Jr, chief executive of Black Enterprise magazine

"When I moved into the same affluent area that Gates lives in, I wondered whether someone might mistakenly report me, a black man, for breaking into my own house in a largely white neighbourhood and how I might prove the house belonged to me. I joked to my wife that maybe I should keep a copy of the mortgage papers and deed in the front foyer, just in case. I do now. And it is no longer a joke." Lawrence Bobo, Harvard professor

"Maybe it was Professor Gates who behaved stupidly, or at least arrogantly. He is, after all, a Harvard professor. I was once a Harvard professor, and my instinct is to side with the Cambridge cops." William Kristol, Washington Post columnist

"Was he frustrated? Loud and assertive? Disorderly? Possibly. It's tough being a perpetual suspect. In his 1994 book, Colored People: A Memoir, Gates wrote that being black was no disgrace, but it could be inconvenient: 'When I walk into a room, people still see my blackness, more than my Gates-ness.' Even when the room is in his own home." LA Times editorial

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments