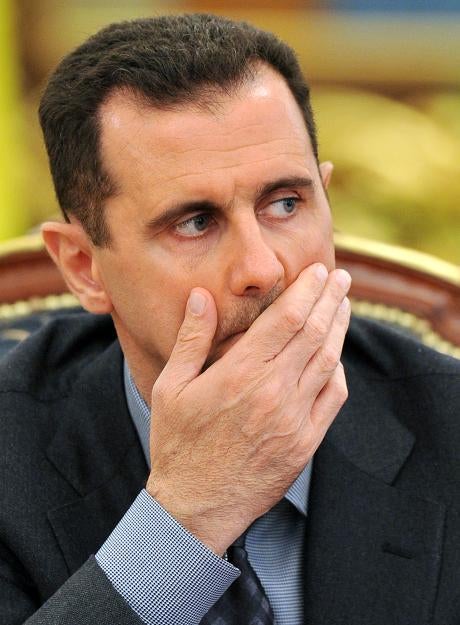

Tensions in his own sect add to problems of Syria's Assad

Rumblings of discontent within Syria's Alawite minority are presenting a new challenge to President Bashar Assad's efforts to retain power in the face of an expanding armed rebellion, calling into question the loyalties even of his own sect in the conflict ravaging the country.

Assad has increasingly come to rely on the 2.5 million-strong Alawite community for support as Syria's Sunni majority has flocked to join the rebellion, sharpening the sectarian dimensions of an uprising that began as a largely spontaneous quest for greater freedoms inspired by the revolts sweeping the Arab world.

Alawites, in turn, have rallied behind Assad's leadership, spurred by fears for their future in a Syria they would no longer run and in which Sunni Islamists may play a major role should the rebels win.

But now, from the Alawite heartland of Syria's northern coastal region come whispers of intrigue and strains within the Assad clan itself. A shootout between members of the extended Assad family in the president's ancestral home town of Qardaha late last month and the detention of a prominent Alawite activist by the regime offer hints of unease within the one segment of the population whose unwavering support for Assad has hitherto not been in question.

There is no indication that Alawites are on the verge of switching sides to join the fragmented and leaderless opposition, which has made little effort to welcome them. Indeed, many Alawites who initially welcomed demands for political reform fell silent long ago or lined up behind the Assad regime once the revolutionaries took up arms and Sunni extremists began to play a more prominent role, according to Alawite activists and residents of the Latakia region, where the minority community is concentrated.

As members of an obscure and little-understood offshoot of Shiite Islam, the Alawites endured centuries of persecution under Sunni rule before Assad's father, Hafez, seized power in 1970 and propelled them into the ranks of the elite. Many fear being relegated again to second-class status or, worse, being killed by Sunnis exacting revenge for the months of bloodshed inflicted by the Alawite-dominated security forces, Alawites say.

The signs of tension within the community suggest at a minimum, however, that the pressures of the 19-month-old revolt are taking a toll on the cohesion of the Alawites.

"The Alawites are critical for Assad's survival. He wouldn't survive a day without their complete support, so the fact that we are seeing tensions is significant," said Hilal Khashan, a professor of political science at the American University of Beirut. "Most Alawites are upset with the regime, and they feel Assad is dragging their sect into a conflict they can't eventually win."

Exactly what happened in Qardaha over the last weekend of September is unclear, and accounts differ over whether the dispute was rooted in political or personal rivalries. But all agree that there was an exchange of fire between two members of the Assad family in a cafe in the mountainous town where Hafez Assad was born and where his body is buried in a vast marble tomb.

One of the men, local strongman Mohammed Assad, pulled his gun after being insulted by another Assad relative, Sakher Osman, the accounts say. Both men were injured in the ensuing shootout, along with as many as six others.

Syria scholar Joshua Landis, who maintains close contact with the community through his Alawite wife, says the gun battle occurred only because Osman insulted Mohammed Assad, known locally as the "Sheik of the Mountain" for his role as the Assad family's premier enforcer in the town. An e-mail from a relative in the area described how Bashar Assad intervened in the dispute, calmed tempers and restored order, said Landis, a professor of political science at the University of Oklahoma.

Mohammed al-Saleh, an Alawite activist in Syria, said the fight was over the lucrative smuggling trade in cigarettes, weapons and other contraband that has thrived among the coastal Alawite clans under the Assad family rule. Attempts to read more into the incident are "nonsense," he said.

But suspicions that the quarrel reflected deeper political differences within the community were fueled by the fact that the shootout took place in a cafe owned by the prominent al-Khayer family, a longtime rival of the Assads; that one of those injured was a Khayer; and that the fight came days after the arrest of a prominent member of the family and a veteran dissident, Abdul Aziz al-Khayer.

Khayer was detained in Damascus upon his return from a trip to Russia and then China as a representative of the opposition National Coordination Board, the Damascus-based grouping that is tolerated by the regime for its relatively moderate stance.

The arrest came amid widespread speculation in the capital that Khayer was being groomed by Moscow for a potential role in a future government, according to a Damascus analyst who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he fears for his safety. Activists who believe the gunfight signaled the emergence of a political split within the ruling Alawite clans say Osman was meeting with representatives of the Khayer family to mull a response to the arrest when Mohammed Assad strode into the cafe to break them up.

The specter of a full-blooded Alawite feud seems remote, if only because the challenges to their survival are so immense that most Alawite clans understand they have to stick together, Landis said. A split within the ruling family would "be totally new, a paradigm shift" in the narrative of Syria's revolt, he said.

"I don't believe it's happening," he said. "But it's clear there's a dynamic in Qardaha that is not in favor of Assad. There's just so many tensions."

Indeed, assumptions of Alawite loyalty to the regime mask a far more complex reality in which traditional clan rivalries are becoming tangled in deep frustrations among the many members of the community who have misgivings about the direction in which Assad is leading them, according to Alawite residents of the coastal region and exiled activists.

A steady stream of coffins arrives daily in Alawite loyalist villages, containing the bodies of Alawite men killed in the fight against the rebels. Women wearing black are a common sight on streets festooned with Assad's portraits. The government has not released casualty figures for its security forces, but if the widely touted number of at least 10,000 Alawite deaths are true, it would mean that Alawite loyalists are dying at a greater rate than Sunnis.

A story, perhaps apocryphal but told often enough to lend it an air of authenticity, goes that a mother, upon being presented with the body of her third and last son to die fighting the rebels, asked the officer: "Are you going to kill every one of us just so that one man may survive?"

Complaints that Alawite fears are being exploited by the regime to protect Assad and his family are growing steadily louder as the death toll mounts, according to an Alawite doctor from Latakia, who spoke on the condition of anonymity while on a trip to Beirut because he fears for his safety.

"Assad is not representing the Alawites, he is using them," he said. "If Alawites are prepared to die for Assad, it is because they fear for themselves, not because they love him."

Most impoverished Alawite communities benefited little from the ascent of the Assads, and they have historically formed an important component of the opposition to Assad's rule, said an Alawite activist in Latakia who spent a decade in jail in the 1990s and did not want to be identified.

But they were heavily recruited into the security services, and they have since been propelled onto the front lines as the accelerating defections of Sunni soldiers call into question the reliability of Sunni units, military experts say. The army is also increasingly relying on groups of armed irregulars known as the shabiha, drawn mostly from the Alawite community, and has been organizing them into local militias.

Sunnis also serve in the shabiha in predominantly Sunni parts of the country such as Aleppo, Daraa and Deir al-Zour, confounding simple interpretations of the conflict as sectarian, Alawite and Sunni activists note.

Many of the large-scale massacres of civilians known to have taken place, such as those in the villages of Houla and Qubair this summer, were blamed on Alawite shabiha, however. And though there have not been any recorded retaliatory massacres of Alawite civilians by the rebels, "the danger of widespread sectarian reprisals . . . is frighteningly real," the International Crisis Group said in a recent report.

Those fears, above all, are likely to continue to bind Alawites to Assad in what they have come to see as a fight for their survival, said Khashan, the professor.

"He has left them with no option but to stay with him," Khashan said. "He has succeeded in linking the fate of the Alawites to the fate of the regime."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks