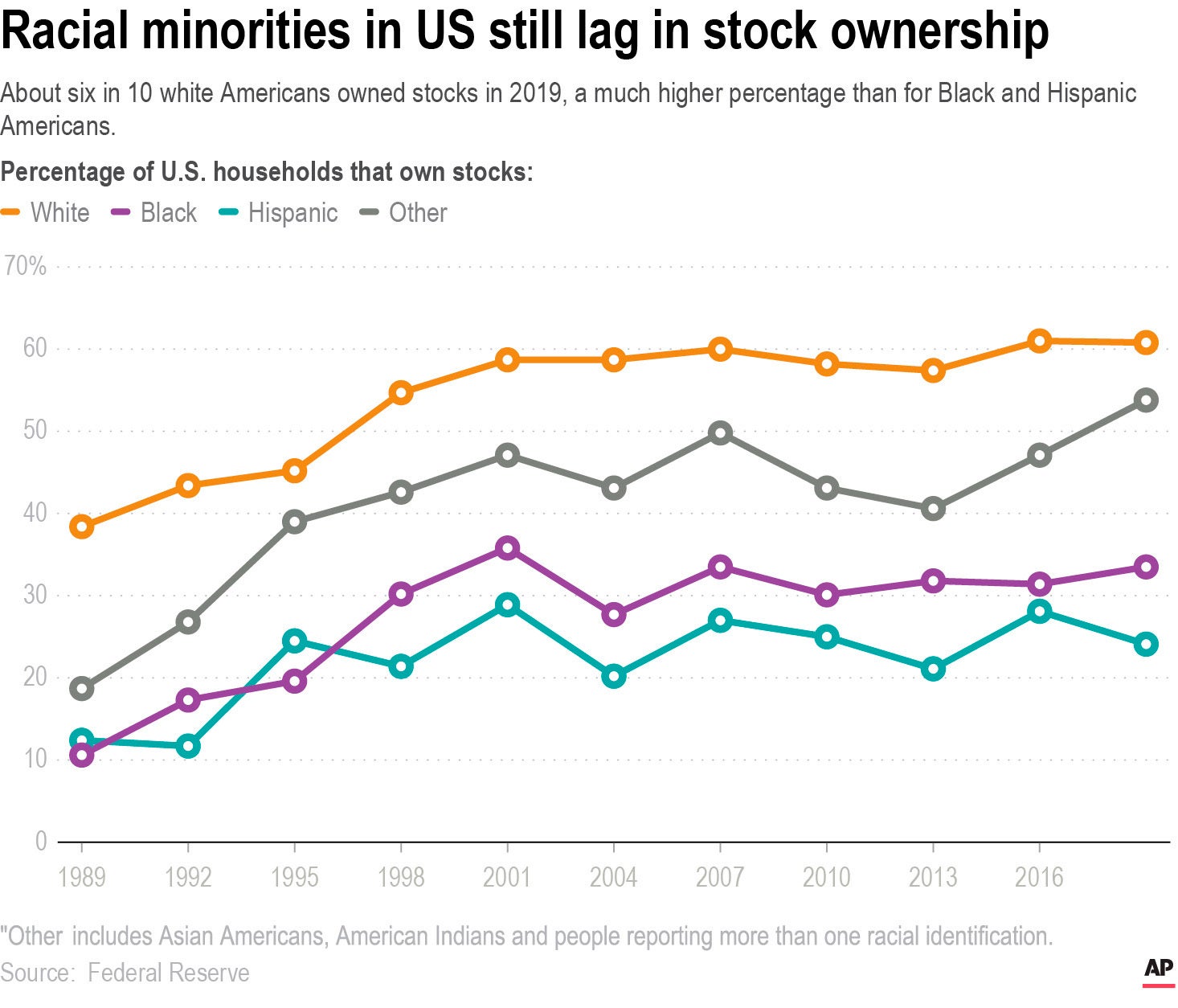

Stocks are soaring, and most Black people are missing out

Nearly half of all U.S. households don’t own any stocks, and a disproportionate number of them are from Black and other racial-minority households

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Americans who own stocks are pulling further away from those who don’t, as Wall Street roars back to record heights while much of the economy struggles. And Black households are much more likely to be in that not-as-fortunate group that isn’t in the stock market.

Only 33.5% of Black households owned stocks in 2019, according to data released recently by the Federal Reserve. Among white households, nearly 61% did so. Hispanic and other minority households also are less likely than white families to own stock.

Many reasons are behind the split. Experts say chief among them is a longstanding preference by many Black investors for safer places to put their money — the legacy, some say, of decades of discrimination and fear. Also, many were never taught what they were missing out on.

“We didn’t have a grandfather or aunt or uncle or mom and dad educating us on the markets because they didn’t benefit from it because of historical discrimination in this country,” said John Rogers founder and co-CEO of Ariel Investments.

Black people have also often lacked the opportunity to build up wealth, park it in the market and watch it grow over time. In general, they have lower incomes, which leaves less money to invest after paying bills. Many also work jobs that don’t offer retirement plans like a 401(k).

But researchers say that even wealthier Black households are much less likely to own stocks than their white counterparts. That means they missed out on the roughly 260% returns for S&P 500 funds over the last decade, and the resulting chance to see their wealth grow.

Lower rates of stock ownership are a small reason for the wealth gap between Black and white families. The most important may be the restricted access Black borrowers had to mortgages and affordable housing through decades of redlining and other discriminatory practices, said Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, in a recent speech.

Researchers say increased investment by racial minorities in the stock market, carried through future generations, could help narrow the wealth gap. Toward that end, industry groups are trying to encourage more Black people to become financial planners, who could then draw in potential investors.

Instead of stocks, wealthier Black households are more likely to own safer investments, such as bonds, life insurance or real estate, said Tatjana Meschede, associate director at Brandeis University’s Institute on Assets and Social Policy.

The largest bond fund has returned less than 40% over the last decade. That’s far below the nearly 257% that the largest stock fund has delivered over the same time. Real estate has also had slower gains.

Malcolm Ethridge, a financial adviser in the Washington area, regularly sees a reluctance to invest in stocks among Black people with enough money to do so.

“My personal opinion is Black Americans tend not to trust things that are not tangible because of our history in this country and things being taken away,” Ethridge said. “It gets passed on to you from generation to generation: to only trust and believe in things you can actually touch.”

“A house, I can put my hands on that and believe in that, whereas a stock is just whatever someone else tells me it’s worth, and I just have to take your word for it.”

Bob Marshall, a banking executive in northern Virginia who is Black and does invest in stocks, said differences in financial literacy education may be one factor. Or, he said, because fewer Black families have wealth that has carried through generations, they may be more wary of risky investments.

Even though the S&P 500 recently returned to a record level, it lost more than a third of its value in less than five weeks before that. That’s part of the implicit bargain in investing in higher-risk, higher-return investments.

“There isn’t a passing down of knowledge from generation to generation,” said Rogers, who founded Ariel Investments in 1983. “It’s the opposite of what I hear from Warren Buffett about the magic of compound interest and how much wealth has been created since he was born. Those kinds of stories don’t happen in Black communities.”

Rogers had a different experience in part because his father introduced him as a kid to a Black stockbroker, who became a role model. Decades later, though, Black people are still rare as financial executives or financial planners. That may make potential Black investors feel that buying stocks is not for them.

Financial advisers say they are seeing a greater interest in stocks among younger Black clients. More of those Buffett-like conversations may be happening around dinner tables.

Gary Simms Sr., a global information security strategist in Manassas, Virginia, began investing in stocks a couple decades ago after a friend pushed him to do better with his money. He was reluctant at first, but now he talks about stocks often with his son, a teenager with his own portfolio.

“Culturally, I think African Americans are not raised to build equity,” he said, “but I do think the tide is turning.”