Shipwreck discovered in Alabama may be remains of last boat to bring slaves to US

Illegal cargo of slaves was smuggled into the US in 1859 by slavers who had placed a bet on successfully flouting the law

The wreckage of a boat discovered on a riverbank in Alabama is thought to be that of the Clotilda, the last vessel to bring African slaves into the US.

The ship wreck, which has not been formally identified, was found when unusually low tides revealed charred wood and rusted metal in a river delta and were spotted by a reporter for Alabama website AL.com.

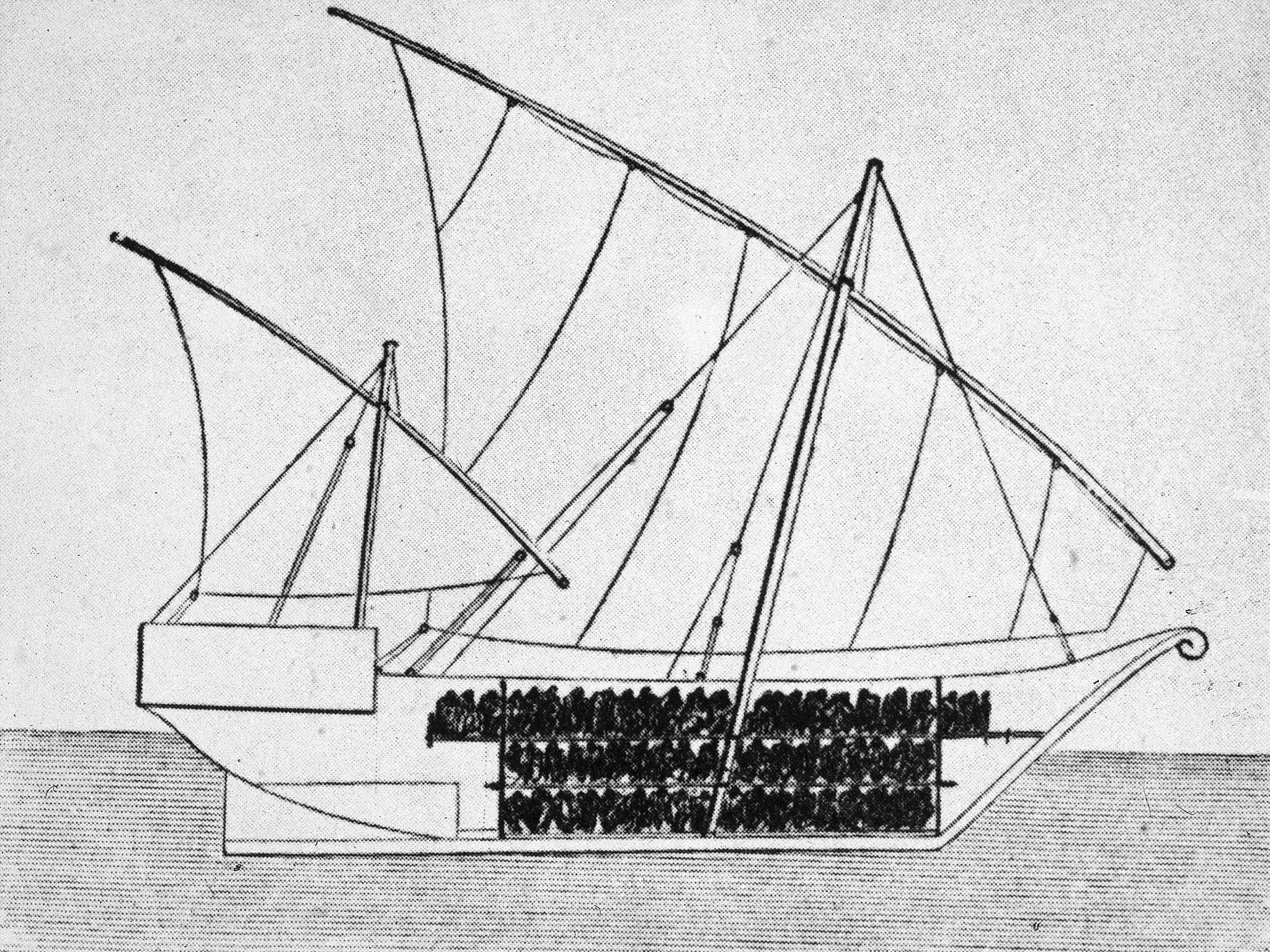

The 86-foot schooner was burned and scuttled after delivering its illegal human cargo at Mobile Bay in Autumn 1859.

Slavery was abolished six years later with the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution in 1865, but it had been illegal to import slaves to the US since 1808.

Despite the law, slavers Captain Timothy Meaher and Captain William Foster had placed a bet that they could smuggle a shipment of 110 slaves from Africa into America.

“These were already rich men, they just did this to prove they could do it”, said Ben Raines, who found the wreck.

When Captain Foster returned, fearful of discovery by the federal authorities, he arrived in Mobile Bay at night and transferred the slaves to the shore by a separate riverboat, before returning to the Clotilda to burn and sink it.

The slaves were put to work in several nearby plantations. They and their descendants remained in the area after the abolition of slavery, naming the community Africatown.

Greg Cook, a University of West Florida archaeologist who examined the wreck, said there were many indications the find was the genuine article.

He told AL.com: “You can definitely say maybe, and maybe even a little bit stronger, because the location is right, the construction seems to be right, from the proper time period, it appears to be burnt. So I'd say very compelling, for sure.”

John Bratten, who works alongside Mr Cook exploring shipwrecks, added there was “nothing here to say this isn't the Clotilda, and several things that say it might be”.

The location of the wreckage matches Captain Foster’s account of where he burnt the boat in an effort to cover his tracks.

In addition, the fire damage, the size and the construction of the vessel are in accordance with the build of the Clotilda and its eventual fate.

“Even to see it in this dilapidated state is remarkable, and I’m really touched”, said local shipwright Winthrop Turner who was examining the similarities between the wreck and the records of the Clotilda’s measurements.

Further excavation is required to verify the find. Mr Cook said the next step is to gather input from the Alabama Historical Commission, other state officials and the US Army Corps of Engineers.

“If it turns out to be the last slaver, it is going to be a very powerful site for many reasons,” Mr Cook said. “The structure of the vessel itself is not as important as its history, and the impact it is going to have on many, many people.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks