Secret state: Trevor Paglen documents the hidden world of governmental surveillance, from drone bases to "black sites"

Secret prisons, drone bases, surveillance stations, offices where extraordinary rendition is planned: Trevor Paglen takes pictures of the places that the American and British governments don’t want you to know even exist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As anyone who has worked there knows, Kabul is a tough place, redeemed by the charm of the people and the abundance of cheap taxis. But Trevor Paglen had trouble finding a taxi driver willing and able to take him where he wanted to go: north-east out of the city along an old back road reputed to be so dangerous – even by Afghan standards – that it had seen no regular traffic for more than 30 years.

Finally he succeeded in digging out an old man who had been driving a cab since before the Soviet invasion. "We started driving and we left the city behind and we're out in the sticks," he recalls, "and we end up in a traffic jam – not cars but goats. And we wait for the goats to go by and we see the shepherd, this very old man, traditional Afghan clothes, big beard, exactly what you'd picture in your head. But he's wearing a baseball hat.

"The shepherd finally turns to look at us in the car – and on that baseball cap are the letters KBR. It stands for Kellogg Brown and Root – a company that was a subsidiary of Halliburton, which Dick Cheney was on the board of. The local goatherd is wearing a Dick Cheney baseball cap!" It was the final clue he needed that this particular bad road was the right road. There in the distance, behind a high cream wall and coiled razor wire, was what Paglen was looking for: the nondescript structures of what he says he is "99.999 per cent sure" is the place they call the Salt Pit: a never-before-identified-or-photographed secret CIA prison.

Trevor Paglen is an artist of a very particular kind. His principal tool is the camera, and most of his works are photographs, but the reason they are considered to be art – the reason, for example, that this bland photo, three feet wide by two feet high, showing the outer wall and the interior roof outline of the Salt Pit, with a dun-coloured Afghan hill behind it, sells for $20,000 – is because of the arduous, painstaking, sometimes dangerous path that culminated in pressing the shutter; and because it reveals something that the most powerful state in history has done everything in its power to keep secret.

Since he was a postgraduate geography student at UCLA 10 years ago, Paglen has dedicated himself to a very 21st-century challenge: seeing and recording what our political masters do everything in their power to render secret and invisible.

Above our heads more than 200 secret American surveillance satellites constantly orbit the Earth: with the help of fanatical amateur astronomers who track their courses, Paglen has photographed them. A secret air force base deep in the desert outside Las Vegas is the control centre for the US's huge fleet of drones: Paglen has photographed these tiny dots hurtling through the Nevada skies. To carry out the extraordinary rendition programme which was one of President George W Bush's answers to the 9/11 attacks, seizing suspects from the streets and spiriting them off to countries relaxed about torture, the CIA created numerous front companies: grinding through flight records and using the methods of a private detective, Paglen identified them, visiting and covertly photographing their offices and managers. The men and women who carried out the rendition programme were equipped with fake identities: Paglen has made a collection of these people's unconvincing and fluctuating signatures, "people," as he puts it, "who don't exist because they're in the business of disappearing other people".

It sounds like the work-in-progress of an extraordinarily determined investigative journalist. But while the dogged tracking of a Seymour Hersh will culminate in a 5,000-word piece for The New Yorker, blowing the lid off, say, alleged American plans to seize control of Pakistan's nuclear weapons or the origin of the sarin used in the Syrian civil war, Paglen is not interested in such narratives. Not that he is uninterested: he describes the extraordinary rendition programme, for example, as "incredibly evil", and has worked closely with human-rights activists. But rather than a charge sheet of the guilty men or calls for government action or popular insurrection, he presents us with a succession of enigmatic images: boring suburban offices, middle-aged men getting into American cars, shimmering lines in the sky, aircraft waiting to take off.

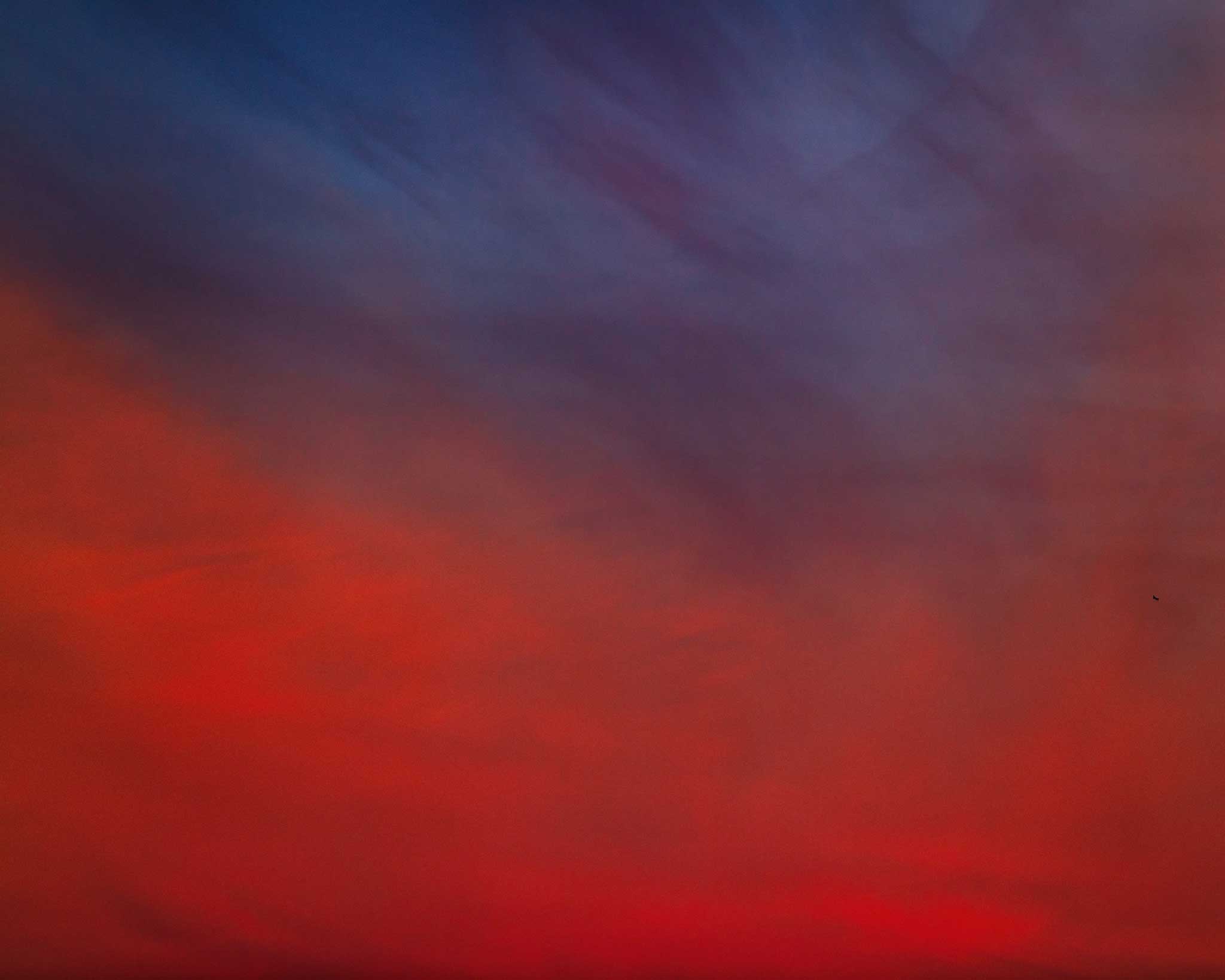

The new project that brings him to Britain is in line with this, though it is also prettier than most of his work. A photograph more than 60 metres wide which will stretch the entire length of the platform of Gloucester Road Underground station – home of the Art on the Underground programme – shows an idyllic expanse of rolling north York moors. And there, nestling among the folds of the hills are the massed giant golfballs of the vast RAF Fylingdales surveillance station, jointly operated with the US.

Given the existence of bitter and determined enemies, what's wrong with having secret facilities to keep a close eye on them?

"I think mass surveillance is a bad idea because a surveillance society is one in which people understand that they are constantly monitored," Paglen says, "and when people understand that they are constantly monitored they are more conformist, they are less willing to take up controversial positions, and that kind of mass conformity is incompatible with democracy.

"The second reason is that mass surveillance creates a dramatic power imbalance between citizens and government. In a democracy the citizens are supposed to have all the power and the government is supposed to be the means by which the citizens exercise that power. But when you have a surveillance state, the state has all the power and citizens have very little. In a democratic society you should have a state with maximum transparency and maximum civil liberties for citizens. But in a surveillance state the exact opposite is true."

Paglen's project is political but it is also philosophical: he is trying to show us the world, k not as the media present it but as it is. And that is a world in which official secrecy has never been so well entrenched, ubiquitous, or extravagantly well funded.

"I'm trying to push perception as far as I can," he says, "so we can create a vantage point to look back at ourselves with very different kinds of eyes – fresh eyes, if you will." He is trying to show us, he says, "the historical moment that we are living in."

The secret world, the shadow of the world as we know it, has of course been with us for as long as human beings have organised themselves in societies. But the attacks on America, cruelly exposing the failings and limitations of the intelligence agencies, produced a bonanza of funding never before seen: the "black budget" of the US defence department, for example, has more than tripled since George W Bush became president and, according to information released by Edward Snowden, was $52bn in 2012. The secret world's shadow is today far bigger and blacker than ever before – and by definition, we the public, whether in the US or the rest of the world, know next to nothing about it.

"Secrecy," Paglen says, "is a way of doing things, of trying to organise human activities, and it has political, economic, legal, cultural aspects. It is a way of trying to do things whose goal is invisibility, silence, obscurity."

So how do we go about trying to see this secret world which, as he says, "operates according to a very different logic from a democratic state"? One analogy Paglen uses is with the attempts of scientists to see the dark matter of which most of the universe is composed. By definition it cannot be seen, but its existence can be inferred by the influence it exerts on the visible universe: the way, for example, that in 2012 the black hole at the centre of the Milky Way bent the progress of a huge passing gas cloud out of shape before finally swallowing it.

But Paglen's task is actually easier than that. "[The secret state] is never completely efficient," he points out, "because stuff in the world tends to reflect light: it's visible. You can't build a secret aircraft in an invisible factory with ghost workers. What I'm trying to do is to get a glimpse into the secret state that surrounds us all the time but that we have not trained ourselves to see very well." He says he has never been arrested doing his work and he is extremely careful not to break any laws, "though of course I am stopped fairly regularly by police and military personnel. I'm calm, tell them what I'm doing, and we work it out."

Paglen's fascination with this world goes back to his childhood: his father was an air-force ophthalmologist and he travelled the world with his family, visiting bases that were often involved in secret missions. As a teenager, he says, "I'd go out drinking with special forces guys… they could never say where they were coming from or what they were doing."

Then while he was working on his geography PhD at Berkeley – back in the days before Google Earth – he was studying US prisons. "I wanted to see where these prisons were, what was around them, why they were in the places they were… When I was going through these archives, I would notice places where the images had been taken out. I started to realise they were not there because some of these military installations are not supposed to be out there. I decided it was incredible to have a blank spot on the map in this information age… I wanted to fill them in and it took off from there. Initially I went into UFO and conspiracy theories, but I quickly realised that there was something much more at stake here.

"The war on terror was getting started and I very early on got the sense that these blank spots on the map were somehow paradigmatic of something that was happening politically." As the World Trade Center smouldered, Vice-President Dick Cheney announced that the nation would have to engage its "dark side" to find the culprits. "We've got to spend time in the shadows," he said. "It's going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective." Paglen had his cue.

In his quest to unveil a world committed to staying hidden, his most bizarre discovery was that America's secret soldiers and airmen wear distinctive uniform patches like regular servicemen, and many of them give broad hints about their work. In his tireless fashion, he tracked them down. Later he was amused to discover that I Could Tell You But Then You Would Have to be Destroyed by Me: Emblems from the Pentagon's Black World, the book in which he collected the images, had become a bestseller among the special forces themselves. "Apparently all of them have that book in their office now," he laughs.

In contrast to the dreary world of the secret bases and prisons, here the secret forces let rip. The images on the patches include a wizard shooting lightning bolts from his staff, dragons dropping bombs, and skunks firing laser beams. One of the more sinister has the Latin tag Oderint Dum Metuant: "Let them hate as long as they fear".

There is a frightening jauntiness about the patches, which express the esprit de corps of a world sure of its hold on our politicians, confident that those who pick up the huge tab will never know anything about it; equally sure, one might say, that they are doing their patriotic duty.

Something of the same smugness pervades the huge photograph about to be exhibited at Gloucester Road Tube station. "It's a very traditional British landscape image," Paglen says. "I looked at a lot of Constable while I was thinking of how to put the image together. What you have is a classical British landscape, rolling hills and little stone houses… The surveillance base is just another element in the landscape."

'An English Landscape (American Surveillance Base near Harrogate, Yorkshire)' by Trevor Paglen, commissioned by TfL's Art on the Underground, will be unveiled at Gloucester Road station, London, on Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments