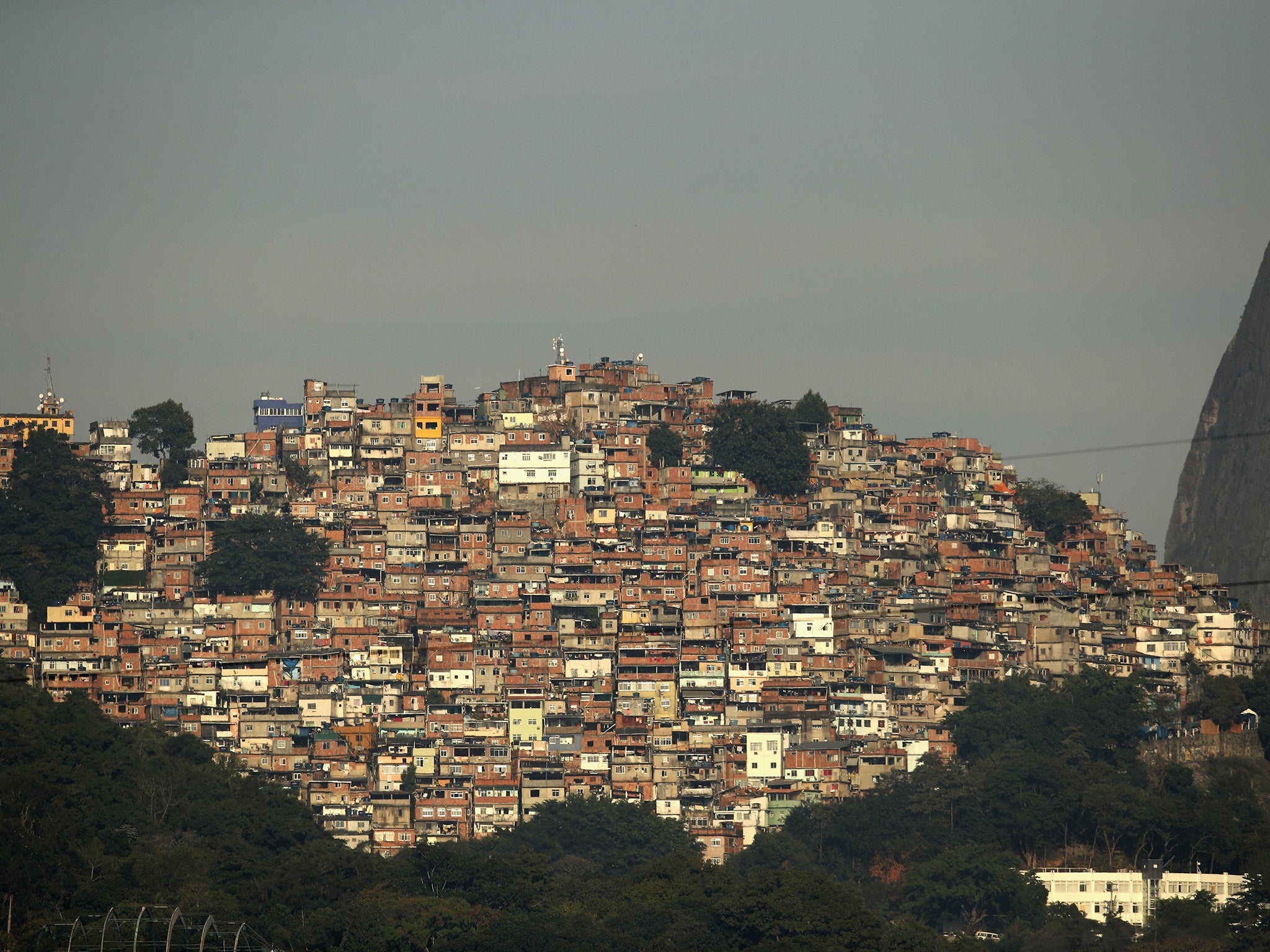

Rio 2016: ‘Microwave’ murders, lost bullets and skull cars: life in the mafia-run favela the IOC don’t want you to see

25 miles away from the Olympic village in Rio de Janeiro lies a dark and broken district ruled by mafias and drug traffickers where the police do not dare set foot without guaranteed gunfire

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the place where the pastel shades of the Rio de Janeiro Olympic livery are nowhere to be seen and where there is not the slightest encouragement to join the sporting party, you must wind down your car windows to enter.

“We must put them down now,” says the taxi driver, whose jokes about entering the Senador Camara favela are nervous and whose anxiety is unsettling. First impressions are benign, if desolate. A litter of pigs is gnawing on the rubbish which has spilled out of plastic bags on the street. A fire burns in the street. But walls have ears in the Senador Camara. The smart, black unmarked car does not belong here. He drops us and goes.

It’s the second time this summer the man behind the wheel has told me he feared that he would be mistaken for police. The same tension applied in La Castellane, the Marseilles suburb where the graffiti on the approach roads reads ‘nique la police’ (‘f*** the police’). But the police don’t even exist in this place and when they do they venture where we are venturing there will nearly always be gunfire. There is a word for the vehicle they travel in: ‘the skull car’ because shootouts and death often come with it.

The kings in places where the usual rule of law breaks down are the mafia. There are three factions vying for control in these vast populous lands known as the West Zone, in the city which would have you believe that it is about sand, sun, samba and staging a great race for Usain Bolt to run. Depending on which place you have wound up, ‘Third Command’, ‘Red Command’ or ‘Friends of Friends’ are in charge. We are in the territory of ‘Third Command’ – a group whose business is the supply of drugs and who dispense their own kind of summary justice.

When one of their number has transgressed a moral code, perhaps committing a crime which attracts the ‘skull car’ into the place, he will be submitted to what is known as ‘The Microwave’, by which tyres are thrown around him and set on fire. Many say it is the way the Brazilian investigative journalist Tim Lopes died when he was working on a report about parties hosted by drug traffickers in another district, Vila Cruzeiro, which allegedly involved drugs and sexual exploitation of minors.

It is testament to the breakdown of law and order that those who live here find it hard to tell you whether they would prefer the police or the perpetrators of the ‘The Microwave’ to be running the place. “That’s a little complex,” says Fabiana Caveirao, who is accompanying us. Though some of the communities are occupied by a Unidade de Policia Pacificadora (UPP), or ‘Police Pacification Unit’, the picture that she, like all Brazilians, paint is of a police service which subjugates the communities they occupy and colludes with mafia.

There is an entire vocabulary for this. An arego is the financial agreement police will regularly strike with ‘Third Republic’ – perhaps when a baile funk party is planned at which the sale of drugs will be organised. “We’re having a party. Leave us alone. You will get a share,” say the mafia. The establishment complies.

When the authorities cross the line and the armoury of R15 and AK47 weapons are fired, there are casualties, though no-one ever seems to know from where and whom the gunfire has come. Bala perdida (‘lost bullet’) they call it. Amnesty Brazil revealed last year that of the 56,000 victims of murder in Brazil in 2012, 30,000 were young people aged between 15 and 29. Around 90 per cent of those young victims were men and 77 per cent were black. Brazil has the highest homicide rate in the world.

It is testament to a community’s inherent will to organise that Senador Camara – named after the railway station built here by the Senator of the Republic in the early 20th century days when the state was respected – wants better.

Ms Caveirao takes us to meet Samuel Muniz De Araujo, or ‘Samuca’ by the nickname which Brazilians always like to give. Operating from a former school which was vacated after being caught in gun crossfire, he has established a form of community organisation – A História Que Eu Conto ("The Story I Tell").

His story tells how adolescents of this place are inexorably drawn under the ambit of the mafia who rule it. When De Araujo was 15 and working as a fisherman on the coast at Cabo Frio, his mother died and he was drawn into criminality; robbery, at first, then kidnap to extort money – a crime which became common from 1988-1990, when he was criminally active.

“I was autonomous and worked independently [of the mafia],” De Araujo says, through our translator. “But then if they needed me I would do things for them. I didn’t create a relationship with them but if they needed a car to be robbed or if they needed someone to help because of the risk of another gang coming into the favela, I would help. Then they left me alone.”

De Araujo’s major hit was on a businessman whose movements he and two accomplices had monitored before seizing from an underground car park. He is reluctant to detail the victim beyond a forename – ‘Sergio.’ “We posed as police officers, arrested him and drove him off in his own car to a condominium on the west side,” he says. “He was trying to avoid the police so there was no trouble when we wanted $200,000 (£154,000).” De Araujo says that after he had tried to kidnap the man a second time he was arrested and sentenced to 15 years in prison, commuted to seven. He says his prison term pushed him away from crime.

There is no evidence of any municipal enthusiasm for De Araujo’s "community centre" where the young of Senador Camara can undertake theatre, dance and art. The former school is a careworn, tumbledown place. The roof is falling in. We speak in a filthy kitchen. A horse grazes on the yard outside. There are signs that a new building will replace this one, which in our own world would be condemned. But no-one seems too sure when that will be.

The money always takes time to arrive here. Mention former socialist president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s famous Bolsa Familia social security system and people laugh. “People who don’t need it get it,” says the taxi driver. “Like politicians.” There is plenty of time to talk to the driver. The journey out from the Olympic centre of Barra is about 25 miles and it takes the best part of two hours, through Rio’s chronically bad and permanently gridlocked roads.

“There is not good management of money. No-one checks where it going,” says Ms Caveirao. She tells of a nation so incapable of governance that it regularly pays out pensions to the dead. She, too, belongs to the fragile pursuit of a better way. Working as a cleaner to subsidise her progress, the 38-year-old has finished a college course in social services and is embarking on a higher degree, examining the need for shared parenting.

The most subtle evidence of the fight-back against mafia rule and its summary forms of justice certainly belongs in the homes. “The Brazil boys’ love of ostentation makes the gangs attractive,” says Ms Caveirao. “The boys who work for them have more expensive things and the girls then go after them because they like ostentation. But there was a time when the criminals would go to talk to parents when a girl began to look like a woman and say: ‘Your girl is going to be mine. And then the criminals would start to watch and bring her in.’ In many cases now the families won’t accept that. They resist that. Perhaps they just run away.”

The level of economic hardship here is less severe than in some of the favelas in the south Brazil, such as the Morro da Cruz community at Porto Alegre featured by The Independent two years ago. But at least they are independent of a mafia down there. “The drug trade here is intense and it controls. You see the power of the big fish. They live like they do in the movies,” says Ms Caveirao.

A short walk through the streets neighbouring De Araujo’s project reveals more prosaic dangers. There is a craze across Rio de Janeiro for flying kites, though many glue broken glass to the string attached to the tails of their crafts to slice through those of others. You can cut yourself walking into those which lodge on low hanging electricity wires. We dodge one which is seemingly conducting the electricity from the makeshift cables. A smell of burning plastic fills the air.

We reach a small matrix of streets where "Third Command" – nor the other two controlling mafias – do not exert control. “It is like Switzerland,” says Ms Caveirao. But she still does not think it wise to photograph or film. “We don’t know which people watch us,” she says.

Motorbikes buzz around manically in the dusk, none with headlamps, while the lights of the supermarket compensate for the lack of streetlamps. And then we reach the railroad, which takes us back to the Barra district, with its ubiquitous Olympics signposts, volunteers and smiles, a mere 20-minute ride away.

“We have no relationship to all of that,” says Ms Caveirao. “That is a totally different life to ours. We don’t even see the menial work which the Olympics is giving. It’s like make-up. It’s not real.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments