Where the wild things are: How to build a primitive community in the age of technology

Lynx Vilden is on a mission – to create a sanctuary free from the trappings of modern-day life and to return to humankind’s ways of the past. Nellie Bowles reports

When the end comes, some will not be waiting in a bunker for a saviour. They will stride out into the wilderness with confidence, ready to hunt and kill a deer, tan its hide and sleep easily in a hand-built shelter, close by a fire they made from the force of their two palms on a stick.

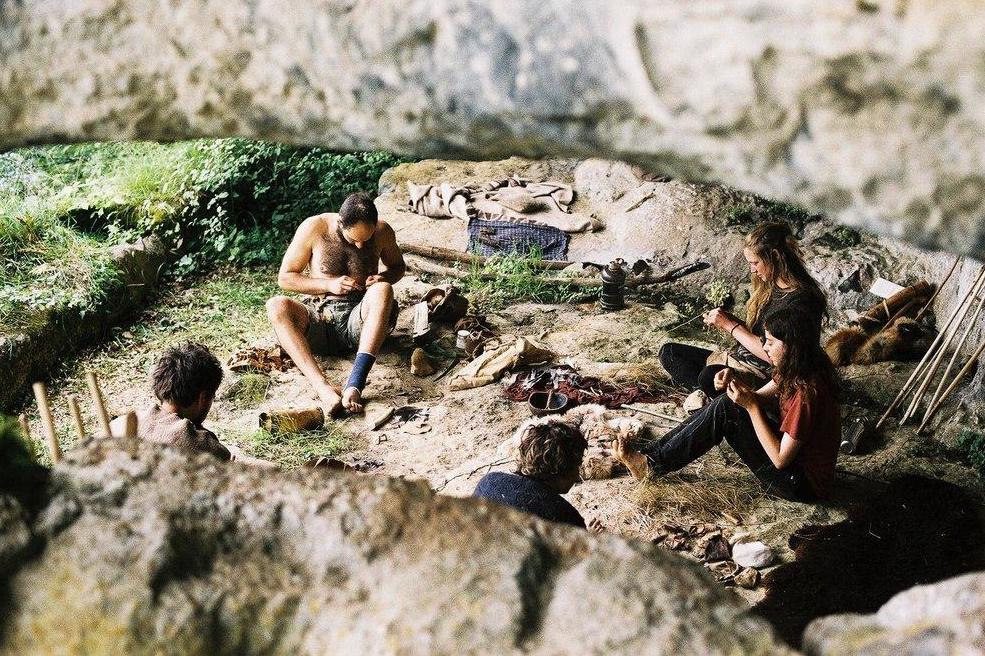

Four hours from the Seattle airport, in a valley called Methow, near a town called Twisp, Lynx Vilden is teaching people how to live in the wild, like we imagine Stone Age people did. Not so they could get better at living in cities, or so they could be better competitors in Silicon Valley or Wall Street.

“I don’t want to be teaching people how to survive and then come back to civilisation,” Lynx says. “What if we don’t want to come back to civilisation?”

Some people now are considering what it means to live in a world that could be shut down by a pandemic. But some people are already living like this. Some do it because they just like it. Some do it because they think the end has, in fact, already begun to arrive.

A couple of times a year, Lynx – she goes by the name professionally, though it is not her legal name – teaches a 10-day introduction to living in the wilderness. When I arrived for this program, Lynx runs to me, buckskins flying, her hands cupped tightly around something that was smoking.

She holds it towards my face. I close my eyes and inhale deeply. Confused, she moves her smoking handful to someone else, who blows on it lightly. It is an ember in a nest of seed fluff. Lynx is making fire. Her property looks like a kidnapper’s lair from a movie. But her dream, she tells those of us gathered, is a human preserve. Her vision is called the Settlement. It will have a school, where people can come in street clothes and learn to tan hides. But to enter the preserve itself will mean giving oneself over to it.

“You walk into it naked and if you can create from that land what that land has to offer, then you can stay there,” Lynx says. “It’s going be these feral rewilded people. I’m thinking in two to three generations there could be real wild children.”

We set up our tents around her property. I have a sleeping bag from high school, a Swiss army knife and a stack of external batteries. It scares me that there is no phone reception. We communicate over the week in hoots. One hoot means hoot back. Two hoots means “gather”. Three hoots means an emergency, like near-death level.

The class may have been there to go ancient, but they brought very modern food requests. In a group of seven, one student is a strict carnivore – Luke Utah, who likes a morning smoothie of raw milk, liver and egg yolk. Another is a vegan. One student says they are so sensitive to spice that even black pepper is overwhelming. One person is paleo, one is allergic to garlic, and one is gluten-free.

Louis Pommier, a French chef turned backpacker, is bartering his skill for attendance. He nods empathetically as he hears these restrictions but would go on to mostly ignore them. The first night he made a chicken curry.

Many of the people who were there came feeling useless in their lives. Some had just quit their jobs. Lynx says many of the students who come for the months-long intensives (another option) are divorced, or on their way to it. Several talk about feeling embarrassed at how soft their hands are, and how dependent they had gotten on watching TV to fall asleep.

We woke up the next morning and gathered around the open fire for boiled eggs. Soon we would learn how to chop down a tree. First Lynx greeted the tree. She puts her hands on it. “If you’re willing to be cut down, will you give a yes?” she asks. She tugs the tree. She calls it a muscle test. Apparently the tree says yes. “We have to kill to live,” she says.

Many students have brought elegant knives and axes from rewilding festivals – there’s a booming primitive festival circuit, with names like Rabbitstick Rendezvous, Hollowtop and Saskatoon Circle – but when confronted with an actual tree they didn’t want to use those. There was an old ax they used instead. Its head periodically flung off, each time narrowly missing someone. The tree eventually fell, a foot from my tent.

The vibe is a mix of Burning Man, a Renaissance fair and an apocalyptic religious fantasy. There is no doomsday prepper gun room – what would happen when bullets run out? Nor is there a sort of kumbaya, gentle-love-of-nature-yoga-class vibe. When Lynx told the story of killing her first deer, she says the deer, wounded, tried to drag herself away.

We shave off the tree’s bark and got to the cambium, the soft inner layer of bark that we would boil in water. This would be used to tan hides. We learn on supermarket salmon skin. We tear into the plastic bags of sockeye salmon with stone shards, then descale the skin with dull bones.

Lynx demonstrates how to process a deer hide using a hump bone from a buffalo. She sent us to go look for bones from the kitchen. Our job is to scrape off the muscle and fat. The hide is heavy, wet and beginning to rot. Sometimes she plays a deer leg flute while we worked.

There is no doomsday prepper gun room – what would happen when bullets run out? Nor is there a sort of kumbaya, gentle-love-of-nature-yoga-class vibe

Lynx looks like Peter Pan, only she’s 54 and with bone earrings. She is thin and quite beautiful, deeply wrinkled in a way that skin doesn’t usually get anymore. One day she wears red grain-on leather pants and her belt buckle was an elk antler crown. Another day it was a coat made of buffalo. She carries a Danish dagger made of a single piece of flint. On her belt is a little pouch made of bark-tanned salmon skin and deer hide holding a twig toothbrush, a sinew sewing cord and a bone needle, a piece of yerba santa for smudging.

She never sits or rests on an object, even to eat. She always crouches. She eats out of a tree burl that she has hollowed into a bowl.

“She’s like a blond-haired blue-eyed dressed up like a North American native person from a century ago, so she’s a striking image that’s easy to capture a lot of people’s attention,” Matt Forkin says. He is a hardware engineer with X, Alphabet’s experimental tech division. He has studied with Lynx, and is also now going in on some land in the Sierra Foothills with friends where they plan to go wild.

There are several of these new rewilding compounds emerging. One of the larger efforts is in Western Maine, where a group is working to replicate a hunter gatherer community. What used to be a handful of bushcraft schools to learn these skills is now an industry of hundreds.

On a walk Lynx finds some deer scat and hands it out, and a bit of stringy inner bark too, some dead limbs, mullein stalks. I ask what kind of plant a branch is called and she bristles.

“Naming something makes people think they know it when they don’t,” Lynx says. “It’s the golden torch light spindle. That’s what it does.”

A group of her former students visit with stew, and we sit around a fire. They have two young children in tow, and homemade plum mead. They started just like us, they say. They were city people, mostly from the Bay Area. I visit their enclave the next morning.

Down a dirt road, past ramshackle cabins and horses, one group of permanently rewilding people have set up a series of yurts and shelters. Epona Heathen used to have a different name and used to live in Oakland, California, working at a thrift store. She felt the call to wilderness while studying sociology at University of California, Berkeley.

“I’m writing this paper and the chair is wobbly, and I don’t know how to fix it,” Epona says of her time in the urban world. “I’m eating eggplant, and I don’t know where it grows.

“One day I was like, ‘This is crap. We live month to month. We spend all our money on booze and coffee. We can’t save like this. We can’t live like this. We all talk about getting back to earth, but we did know anything about it.’”

After some time on organic farms, they found Lynx. They decided to stay for a six-month Stone Age immersion.

“We had to come with 15 tanned hides and 5 pounds of dried fruit and 5 pounds of dried meat,” she says.

Her partner Alex, who is 31 and who worked at a grocery store as a wine specialist, bought a property nearby. Now about a dozen young people live there. Epona’s yurt is 16 feet around and 12 feet tall, with a small wood-burning stove. She built curved bookshelves along the wall. Most of her food and medicine is dried in jars. There is a cat named Kitty and a dog named Arrow. She identifies as an animist.

“People say, ‘Oh when the apocalypse comes. ...’ What are you talking about? It’s here. I’m a collapsist,” she says. “I’m not invested in maintaining the comforts we have.”

In our lifetime there is a very high chance we will see major social collapse. I do think there will come a time when these skills are practical for a large number of people

Alex grew up in Montclair, New Jersey, and inherited some money. He is bald, muscular and tattooed. He says he used to be more dogmatic about living primitive, but that is changing. “I just moved out of my yurt and into a house,” he says. “I got a second truck.”

Roxanne, who has bright curly red hair, is here for community, she says. She’s working alongside Alex, rubbing salt into hides. She just moved a couple weeks ago and had been working at a coffee shop before this. “You know, the thing about living the dream is it’s really hard!” she shouts, hauling another salt bag.

There is a main house down the hill, with a landline that everyone shares. The place is decorated in skulls and massive birds. There is a buffalo strung out to dry outside and a tall stack of deer legs at the door. More fit and dusty young people lounge inside. They were roasting a deer leg.

A sense of collapse underlies their opposition. “From a purely rational engineering mind looking at the trends in the data, exponent times an exponent, our utilisation of natural resources is way beyond the natural carrying capacity of the earth, and we’re seeing that in essentially ecosystem collapse,” Matt Forkin had told me. “In our lifetime there is a very high chance we will see major social collapse. I do think there will come a time when these skills are practical for a large number of people.”

Alex makes a gesture towards the small town over the hill and down the road. “Everyone is partying their final days away,” he says.

Lynx is padding around in wool in her little cottage at the end of the property. She sleeps indoors in the winter. Her home is all exposed wood and overflowing planters, horns and old rattles. She is prickly and suspicious, upset that I had left her property to visit the Heathens.

Her daughter, Klara, lives in Washington DC. Klara’s boyfriend works for the World Bank.

“When I met him,” Lynx says, “my first question was, ‘Do you hunt?’ No. ‘Do you chop wood?’ He says, ‘I could try.’”

Lynx is single, and that is starting to bother her. “The hard part is finding a partner to share it with,” Lynx says. “Maybe I’m getting to the point where people get fixed in their environments.”

She had a traditional childhood with traditional parents in London but left at 17 to play music. She moved to Sweden, went to art school. One day she met a man and they moved to Washington state to backpack. She went into the woods. For a while, she was married to a man named Ocean. They had Klara. She home-schooled her in the mountains in Montana, but Klara went to live with Ocean. Lynx went farther into the wilderness.

But even she cannot escape money, yet. A week-long class costs $600 (£470). “I have to have my foot in two worlds to maintain some semblance of how I want to live in this world,” she says. Klara answers email for Lynx.

In September, Lynx will lead another fully Stone Age project, marching into the nearby public lands. All clothes must be handmade, all food gathered. Lynx’s family still lives in London, mostly. Her sister is a freelance conservator.

We imagine that someone striking out into the wilderness is doing so to get away from everyone, to be alone. The people I met wanted the opposite. They want a life where they cannot survive even a day alone. They cannot get food alone, cannot go to the bathroom, cannot get warm alone. They want to be dependent.

“The city is actually the place of rugged individualism,” says my classmate Joan, who grew up in suburban Philadelphia and uses the pronoun they. “Here I’m using my hands and with people all day.”

Before being in the wild, they were addicted to video games and loved social media; very soon, Joan says, they were going to smash their smartphone. They were wearing a thick vest they had felted, with a full marten, body and head, sewn in as a collar for warmth.

“Some people don’t get it, but I prefer this life,” Joan says. “No, I don’t use toilet paper. I use moss and I like it better.”

Really coming back to nature means responding to the social responsibility too. Someone says you have this personality flaw, you can’t just avoid them. You have to respond. You adapt

Together, in the wild, everyone has to soften. One night, one of the guys said something offensive about gender roles, and a couple of us got annoyed. Then we all had to stop arguing because there was no one else to be with. I started arguing about politics with someone. Instead of going away, he had cold contraband beer, and I had nothing better to do than learn more about him. My only entertainment was the people around me. It made them more interesting.

“Really coming back to nature means responding to the social responsibility too. Someone says you have this personality flaw, you can’t just avoid them. You have to respond. You adapt,” Epona says. “Rugged individualism is a lie. Rugged individualism cannot survive.”

“There’s a social skill set of working in a community,” Luke Utah says.

At one point, I got separated from the group. There was nothing I could do. I checked the river. I checked the houses. I checked the little pine needle burrows where people sometimes slept. I hooted once. I hooted twice. I sat and waited in a terror while it got dark.

Our time makes social obligation largely unnecessary. When I moved apartments, I hired TaskRabbits. When I got cold, I turned on the heat. In the woods, the evening entertainment I got was what we could provide one another. Now, suddenly, I did not want to be alone for a minute. The dependence felt amazing. I shrieked with joy when the group came jaunting back.

The next time I went to town, I dreaded the spasms of my phone wriggling back to life. I could feel the reception in the air, could feel being alone again. I was relieved to cross over the hill, out of service and back again to Lynx and my friends.

Deer legs are very useful. Their toe bones can be whistles and buckles and fish hooks. The leg bones become knives and flutes. Tendons become glue. I pop the black toes off into boiling water. Slicing with obsidian, I peeled the fur off and then the muscle and tendons. I sawed the ends off the bone. I used a twig to oust the marrow. The carnivore ate it. This would be my flute.

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks