Restaurants show diners what a day without immigrants tastes like — or doesn’t

The strike was intended to hit all businesses, but the restaurant industry– where immigrants make up a quarter of the workforce – seemed most affected

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It wasn’t long into Thursday night’s dinner service at a Bloomingdale pub, the Boundary Stone, before Colin McDonough forgot to fire up a customer’s order of wings. “Fire the fry cook,” joked Gareth Croke, who was flipping burgers nearby. Croke can’t fire McDonough: the two are co-owners of the restaurant, and they stepped in to cook when almost all of their kitchen staff took a paid day of leave to participate in the nationwide “A Day Without Immigrants” strike.

It was McDonough’s first time working the line. He already knew how valuable his employees are, but their absence drove the point home even harder.

“Honestly, without immigrants, the restaurant industry wouldn’t exist,” he said.

Across town at Bar Pilar, bartenders and friends of the staff were filling in for chef Jesse Miller’s cooks, all of whom took the day off to protest. Matt Roper works at a trade association by day and hasn’t worked in a restaurant since he was a teenager. But after friends at the restaurant told him about the strike, he decided to pitch in and spent the evening frying chicken and calamari.

“It’s a little bit of a change from Blue Apron,” he said, referring to the mail-order meal assembly kits.

Such was the scene at restaurants across Washington and many other cities on Thursday when immigrant workers, with their colleagues’ support, stayed away from their kitchens and host stands, and instead marched in protest of the Trump administration’s hard-line approach to immigration policy. Immigrants decided to hit Washington – a city that loves small plates and happy hours – where it hurts: in the gut.

“I think that it will give a message to all of the people that think that we are not helpful in this country,” said Saul Canesa, a green-card-holding Salvadoran chef at El Chucho in Columbia Heights.

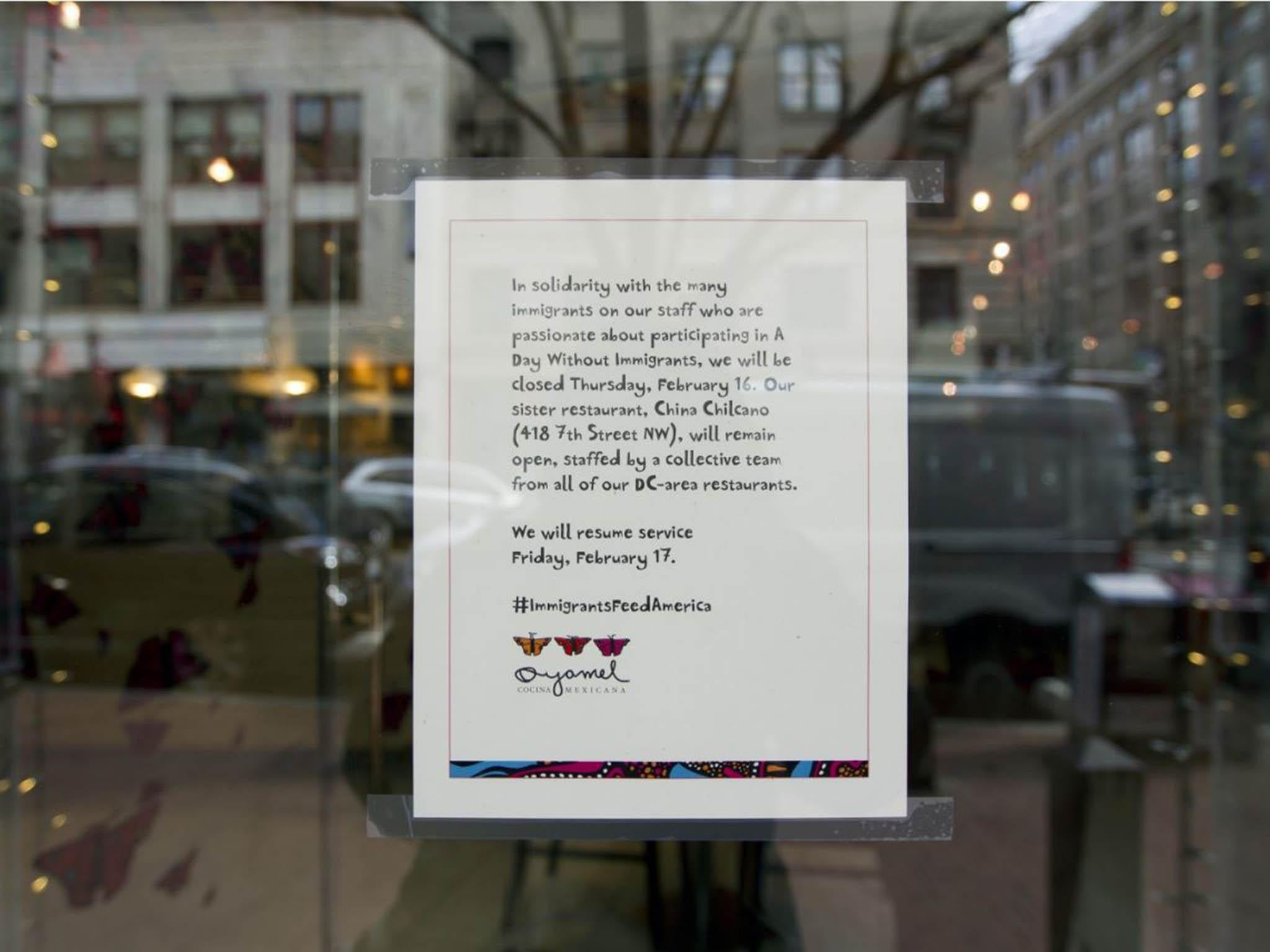

The strike was intended to hit all businesses, but the restaurant industry – where immigrants make up nearly a quarter of the national workforce, according to the Institute for Immigration Research at George Mason University – seemed to be worst hit. Locally, a flier calling for the strike had been circulating among workers and, according to Univision, no one seems to know who started the whole thing. But things seemed to really take off when José Andrés, the outspoken Washington-based chef, who became a citizen in 2013 and is currently embroiled in litigation with President Trump, announced that he would close many of his restaurants.

Announcements snowballed after that. On Wednesday, restaurants met with their staff to decide: would they close entirely, open with a partial menu and partial staff, or do business as usual?

Some opted for the latter, because their employees wanted to get paid. Some, including Sweetgreen and DC Empanadas, closed and paid their staff anyway. Others that stayed open, including the Royal and Anxo, vowed to donate proceeds to Ayuda, an immigrant advocacy organisation. Still others were forced to close because of no-shows. A news release from the Pentagon on Thursday noted that its concessions committee “learned this morning” that employees were participating. Some fast food restaurants in the Pentagon including a Starbucks, Taco Bell and Burger King, also closed.

Donnavon Lalputan, who is originally from Trinidad, wasn’t being paid for the day he missed at Hank’s Oyster Bar on Capitol Hill, which closed for the strike. But, he said: “We were given the opportunity to express ourselves, which is priceless.”

In some cases, unnerving incidents motivated participation. Maziar Farivar, the Iranian-born chef-owner of the Peacock Cafe in Georgetown, said that shortly after President Trump’s inauguration a young white man walked into the restaurant and raised his hand in a ‘Heil Hitler’-like salute. He then asked about the staff’s immigration statuses, as if he were an agent of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“The fact that people feel permitted to behave that way is a shocking thing to me,” Farivar said.

Most of Farivar’s staff decided to strike, so he closed the restaurant. One of his veteran servers, Kenny Guevara, first heard of plans for the strike about three weeks ago on Univision. She was born in El Salvador but moved at age 10 to America with her parents and became a naturalised citizen. Still, she admitted, she’s scared. Fellow immigrants “don’t talk about a future in America anymore,” she said, “and if they talk about their future in America, they talk about it as a maybe.”

Not every restaurateur was enthusiastic about the strike. Mark Bucher, a partner in Medium Rare and Community, said that he supported the strike and the dozen or so workers at his firm who opted to take a paid day of leave. But he criticised the timing of the action. “It’s a white-hot political climate in Washington right now, and you never throw fire on something that’s white hot,” said Bucher. “You could get a knee-jerk reaction.”

He feared retaliation from immigration officials, and he was worried that the protests would escalate: “All it takes is one dummy to fire somebody.”

Customers weren’t sure how to react to the strike, either. Was going out an act of solidarity with immigrants or counterproductive? Suki Lucier, who works for the government, debated what to do. “When we thought about it, ethically, I wanted to be supportive,” she explained over drinks at Boundary Stone, which she chose because of the owners’ commitment to paying absent workers that day.

At Pizzeria Paradiso in Dupont Circle, owner Ruth Gresser was stretching out balls of dough. She rarely works during dinner service, but getting back on the line – where she was later joined by Hank’s Oyster Bar chef and owner Jamie Leeds – was “like riding a bicycle,” she said. She gave all of her immigrant employees a paid day off, and closed all of her restaurants except the P Street location, which she hoped would demonstrate “what it would look like for us to be open without immigrants”.

What did it look like? Her director of operations, Matt McQuilkin, admitted to accidentally tearing a pizza. Gresser had to remove a pizza cutter from the edge of the oven, where it might have burned someone’s hand.

“The people who do this every day: they’re faster, they’re more proficient,” said Gresser. “We’re not the best crew. But we’re working through it.”

Tim Carman and Becky Krystal contributed to this report.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments