Pulitzer sought for reporter who broke story on Nazi Germany's surrender

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

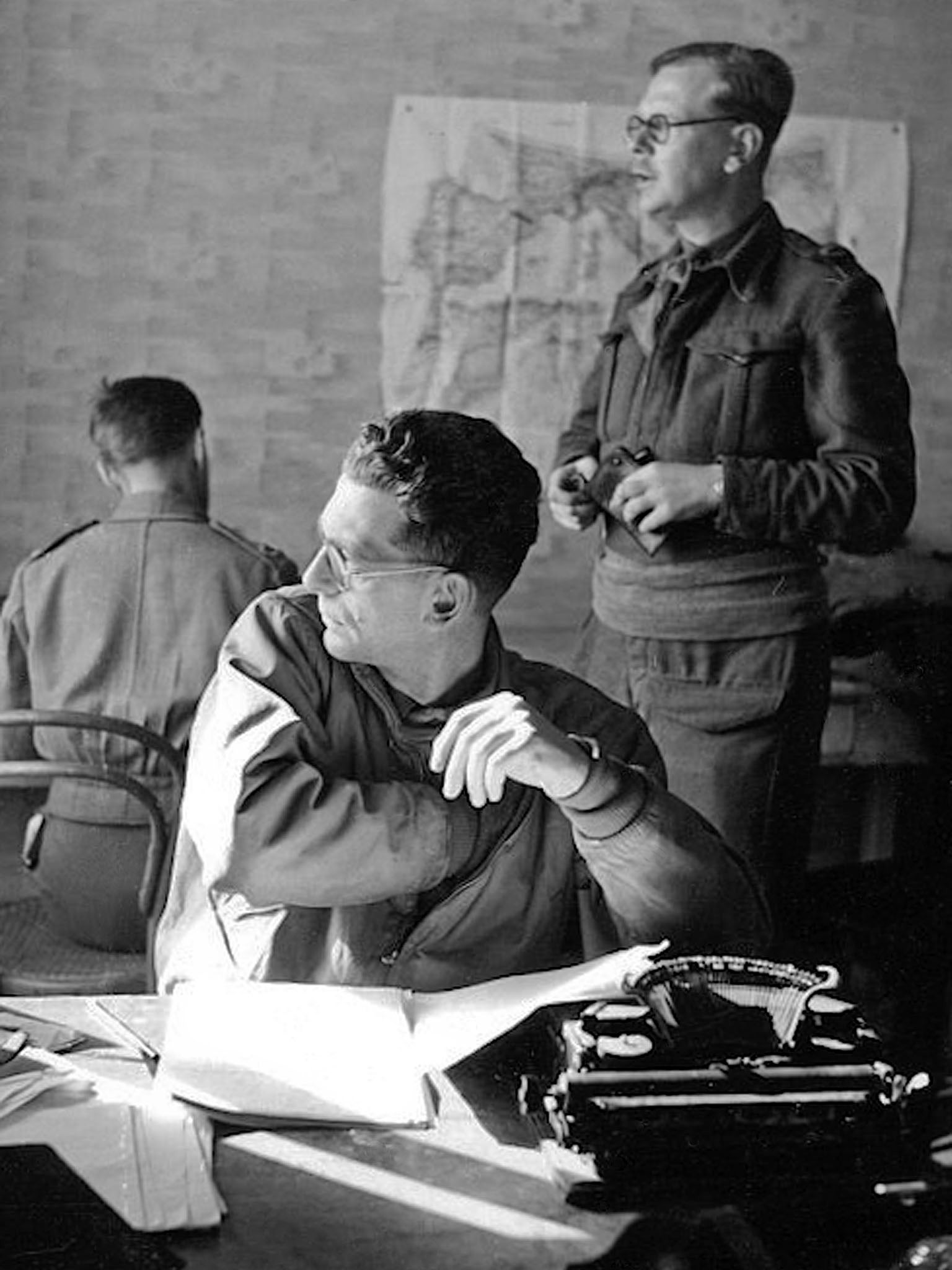

Your support makes all the difference.In headier days, Ed Kennedy personified the hard-drinking, hard-charging war correspondent of another era. The first time his future wife saw him, he was sidled up to a hotel bar in Paris with none other than Ernest Hemingway, both of them so "dead drunk" they could hardly stand.

Kennedy was a star Associated Press correspondent with a penchant for daring evasion of authority, dashing into World War II battle zones where he wasn't supposed to go because he had to get the story. He just had to.

But it was the biggest scoop of his career — Nazi Germany's unconditional surrender — that ruined his career. And a determined group of prominent journalists want to do something about that.

They want Kennedy to be posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize, a recognition of a singular moment of courage when a star correspondent defied political and military censorship to file one of the biggest stories of the century.

"The way a craft evolves is that somebody has to define the edges, the boundaries," says Kim Komenich, a Pulitzer-winning news photographer who is among 54 journalists pressing for Kennedy to receive a Pulitzer. "Ed got it right."

On May 6, 1945, U.S. military officials ushered Kennedy and 16 other correspondents onto a plane in Paris. The plane was airborne before they learned the purpose of the trip: They were flying to Reims, France, to witness the signing of surrender documents ending the largest conflict in world history.

Kennedy chafed at being controlled. The reporters on the plane were "seventeen trained seals," he observed acidly in a memoir, "Ed Kennedy's War: V-E Day, Censorship, & the Associated Press," that was published this spring, nearly a half-century after his death.

Their military handlers insisted that news of the signing be kept secret for several hours. But after they returned to Paris the embargo was extended, not for security reasons, which might have been an acceptable rationale, but for political reasons, Kennedy learned. It turned out that Russia's leader, Joseph Stalin, wanted to stage a signing ceremony of his own to claim partial credit for the surrender, and U.S. officials were interested in helping him have his moment of glory.

The correspondents complained, but the military wasn't budging. They had to hold the story. But then something happened that changed Kennedy's mind and his life. He got word of a German radio report announcing the surrender.

The story was out, but the U.S. censors were holding fast.

Kennedy went to his room at the Hotel Scribe and stewed for 15 minutes. Then he found a military phone that he happened to know wasn't monitored by censors. At 3:24 in the afternoon, he placed a call to the AP's London bureau.

"Germany has surrendered unconditionally," he said, according to an account of the call by the AP's outgoing president, Tom Curley. "That's official. Make the date Reims, and get it out."

Ed Kennedy's story ran big in newspapers around the world. It should have been his greatest moment, but it became an ordeal. The military revoked his credentials, but that was the least of the indignities. His fellow correspondents turned on him, voting 54-2 to condemn him. And the head of the AP — the Philadelphia Bulletin's publisher, Robert McLean — apologized for Kennedy's report rather than praised him.

Kennedy was summoned back to AP headquarters, where his bosses refused to accept his resignation but also refused to give him any work. Several months later, he discovered more than $4,000 in his checking account — it was a severance, though, no one had the courtesy to tell him he was being fired. "They did it in the most cowardly way," says Kennedy's daughter, Julia Kennedy Cochran, a former journalist.

After being cut loose, Kennedy moved west, working for two years as managing editor of the small Santa Barbara News-Press, then shifting to Monterey, where he became editor of the Monterey Peninsula Herald, "a sad, little newspaper" that he turned into an award winner, Cochran said. It was a steep drop from his days as a star war correspondent, but Kennedy seemed to embrace it nonetheless, writing editorials, covering city councils meetings and editing copy

Ray March, who was a young reporter at the paper, remembered walking into Kennedy's office and seeing the framed front page of the New York Times with his boss's byline under the story of the German surrender. "This isn't just your run-of-the-mill editor of a small newspaper," March recalls thinking.

March was too intimidated by the imposing, no-nonsense editor to drink with him after hours at the Quarterdeck Bar in a nearby hotel as the more senior reporters did. And he quaked when Kennedy hollered across the newsroom at him after he filed one of his first stories, which included the phrase "paradoxical dichotomy" in the opening paragraph.

"You write just like I wrote when I was your age," March recalls Kennedy telling him. Then there was a long pause. "And I can't think of anything worse."

He wanted to teach the kid a lesson: Just tell the story, don't try to dazzle with your vocabulary.

Kennedy had divorced by then, but his daughter would spend her teenage summers in Monterey with her chain-smoking, book-loving, exacting reporter of a father. She recalls a devoted, enthusiastic dad who, at times, inexplicably "seemed kind of depressed and sort of morose about something he wouldn't talk about."

Later, she would wonder whether he had second thoughts about his decision on that long ago afternoon in Paris, even though he publicly declared he would have done it all over again.

One rainy night in November 1963, a sports car knocked Kennedy off his feet as he was walking home. He lingered in the hospital for several days before dying at age 58. The doctors found a cancerous tumor in his throat; his cause of death was listed as cancer, complicated by the injuries he'd suffered.

He'd been a prolific writer and, of course, there was an editorial he'd just penned waiting to be published. His editors ran it while he lay in the hospital. "One of the problems of publishing a newspaper is that you have to sell something that is dead," the piece read. "We can sell these pieces of dead trees only by creating the illusion that they are alive. This we attempt to do, with varying success, by headlines that grip the eye and written material that clutches the heart and soul of man."

After the funeral, Cochran's mother, Lyn Crost — a former war correspondent herself — took her daughter to Kennedy's office. Her mother knew there was a treasure to be found: The manuscript Kennedy had written back in 1951 and never been able to find someone to publish.

Over the years, Cochran tried to read it. But she could never finish it. It was too painful to recall the father she'd lost when she was just 16.

She kept it packed away for more than 40 years, through marriage and divorce and a career change. Eventually, in retirement, she found time to read it anew and to gain a deeper understanding of the father she'd lost.

She set about searching for someone who would let her father tell his story. The publisher she found — Louisiana State University Press — didn't tell her who they'd asked to write the introduction. It was Curley, the AP president. She was "overjoyed" when she read what he'd written, sentiments that he said Kennedy's former bosses and the AP's board of that era "could not admit."

"Edward Kennedy," Curley wrote, "was the embodiment of the highest aspirations of the Associated Press and American journalism."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments