The epic rise and fall of Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs

From Harlem to Hollywood — including the 1990s East Coast vs. West Coast rap rivalry, recent sexual harassment lawsuits, and the name changes from Sean Combs to “Love” — Sheila Flynn explores Diddy’s wild and legally fraught path to fame

There was unbridled delight – and more than a little trepidation – across the face of a man who built his image on swagger as Sean Combs took to the stage at Howard University’s May 2014 commencement. He’d dropped out of the renowned institution decades earlier, taking a gamble on a record label internship that spawned an empire touching the spheres of music, fashion, dining, business and, ultimately, pop culture near-ubiquity.

The world of higher education, however, was one that Combs had never conquered in the same way. He grinned like a child in thrilled disbelief as he accepted his honorary degree, then took off his tasselled cap, wiped the sweat from his brow and composed himself before launching into an uncharacteristically humble speech.

“You cannot achieve success without failure,” said Combs, a master of reinvention who’d already changed his name from Puffy to Puff Daddy to P. Diddy to Diddy. “Some of my biggest successes come from my biggest failures.”

In the audience were a cast of this-is-your-life characters who had figured largely in Combs’ rise: The record label bigwig who’d hired him, fired him, then become an executive at one of Combs’s new companies. The women who’d borne his children. The mother who’d raised him. He looked out at those faces as he described learning, while searching through microfiche headlines in the Howard library during his early days on campus, that his father had been murdered in a drug deal gone bad – as opposed to being killed in a car accident, as his mother had told him. So Combs, then 44, also spoke about breaking patterns.

“I decided to embrace the entrepreneurial spirit of my father, but in an honest way … in a legal way,” he told those gathered.

It was a statement that likely sparked raised-eyebrow incredulity among those in the audience who’d opposed the selection of Combs for commencement speaker; not only had he dropped out of Howard, but he’d also courted controversy for almost the entirety of his career – much of it legal.

Now, Combs is embroiled in lawsuits and criminal investigations of an entirely new level. His homes have been raided, an associate arrested, and he’s stepped down as chairman of Revolt, the media company he co-founded, amidst allegations of sex abuse and sex trafficking.

For a man who un-self-consciously likes to define his life by “eras,” this may be the most challenging one yet. And it may be one from which even his trademark tunnel-vision determination can’t save him.

Humble Harlem beginnings

Combs, born in 1969, has spent more than 50 years displaying a single-minded drive for power, success and recognition – and a refusal to back down, instilled in him from childhood. The apple didn’t fall far from the tree; he has described his parents as the “fly guy” and “fly girl” of their Harlem neighbourhood, and both were go-getters in their own right.

His father worked for the Board of Education and as a driver before his 1972 murder, after which Combs’ mother Janice, a former model, worked four jobs to support her son and daughter, Keisha. She emphasised education but also the importance of establishing dominance – a lesson she hammered home to Combs aged nine when another child stole his money.

“My mother wouldn’t let me in the house,” Combs told Oprah in a 2006 interview. “She said, ‘Go back out there and get that money — and if anyone ever puts their hands on you, make sure they never do it again.’ She knew the reality — if people smell weakness, they take advantage of you. You have to defend yourself.”

Janice’s lesson may also have aligned with his natural inclinations, though; his future “Puffy” moniker stemmed from childhood tantrums.

"Whenever I got mad as a kid, I used to always huff and puff,” Combs told Jet magazine in 1998. "I had a temper. That’s why my friend started calling me Puffy."

While Combs clearly took his mother’s advice to heart, he also mirrored her work ethic; he got his first job at 12 – a paper route – then worked at a gas station and a Mexican restaurant, in addition to selling lemonade, he told Forbes. He spent a a childhood summer with an Amish family in Pennsylvania through the non-profit Fresh Air Fund for inner-city kids – and it wasn’t long before his mother moved the family from crowded uptown Manhattan to Mount Vernon, a suburb of Westchester County.

She enrolled Combs, who was raised Catholic and served as an altar boy, at prestigious Bronx all-boys academy Mount Saint Michael – where he wore the neat attire each day, played football and, always one to set his sights high, “just knew I was going to be an NFL pro player,” he told the New York Times in 2012. After he broke his leg, though, Combs had to alter his dreams – and it was at Howard that he truly began to flex his muscles of influence and impresario.

The college years

Combs, by all accounts, began making a name for himself almost immediately after heading south to D.C. to begin his studies at Howard, the historically black university. He arrived at the tail end of the 1980s, when New York-based hip-hop culture was pre-eminent, and Combs cashed in on that Empire State connection.

He wore flashy clothes, threw parties, and began building an entourage. And between classes he “still found time to run a shuttle service to the airport, to allegedly sell old term papers, and to even hawk T-shirts and sodas,” according to Ro Ronin’s 2001 book Bad Boy: The Influence of Sean ‘Puffy’ Combs on the Music Industry. After protesting students took over an administrative building, he turned newspaper and magazine clips about the incident into poster-size collages and sold them back to the participants, Ronin writes.

"When Puffy came, he was a very flashy guy," the book quotes classmate, friend and fellow undergrad promotor Deric Angelettie as saying. "He was always out at the clubs, and the young girls loved him. He’d be in the middle of the floor doin’ all the new dances. And his style of dress was a little more colorful, bolder. Everyone took notice of this cool, overconfident young dude. I was deejaying at the time, and one night he came up to me and said, ‘I’d like to throw a party with you. You’re pretty popular.’"

The pair began organising events that Combs successfully lobbied celebrities to attend – while shrewdly including his own name on promotional materials, including the one that would make him famous: “On his first business card, in the bottom left-hand corner, he had engraved "Sean (Puf) Combs,” Ronin writes.

“For the next two years, we threw one damn [party] near every week," Angelettie says in the book, including a homecoming at a Masonic Temple where they “expected maybe fifteen hundred.

“Forty-five hundred people came. The D.C. police shut down the whole block and brought out the dogs. We had to get on our knees and beg them not to lock us up."

As Combs’ endeavours burgeoned, however, so did his ambition – which soon outgrew the Howard campus. He began lobbying record executives in New York for jobs but soon lowered the ask to internship, securing one with Uptown Records’ Andre Harrell, who famously coined the term “ghetto fabulous.”

Combs initially commuted weekly between college and his hometown, working 80-hour weeks as he literally ran to complete errands for his record superiors, and it wasn’t long before he quit Howard altogether. By 1991, Harrell had installed him as an A&R executive, and Combs was forging a reputation for identifying and moulding top-tier talent.

Tragedy strikes in New York

The New Yorker displayed cross-cultural perspicacity that would become a hallmark – and gold mine – of his career. He threw weekly “racially mixed "Daddy’s House" parties … for street kids and preppy students from Columbia University and New York University” where “he saw what fans were dancing to and wearing,” writes Ronin.

With the help of his girlfriend, Def Jam intern-turned-stylist Misa Hylton, Combs was dialling into street trends and the youth zeitgeist as he promoted artists such as Jordeci – but one of Combs’ trend-setting events featuring the R&B duo took a tragic turn in 1991.

Combs had helped set up a charity basketball event at Harlem’s City College Campus just after Christmas – but 5000 turned up and a stampede created a crowd crush in a stairwell killed nine and injured around three dozen others. No criminal charges were filed, but Combs gave testimony about the tragedy several years later in a lawsuit filed by victims against the college, describing “young ladies getting squished” and the “panic on everybody’s face.”

‘’City College is something I deal with every day of my life,’’ Combs said outside court in 1998. ‘’But the things that I deal with can in no way measure up to the pain that the families deal with. I just pray for the families and pray for the children who lost their lives every day.’’

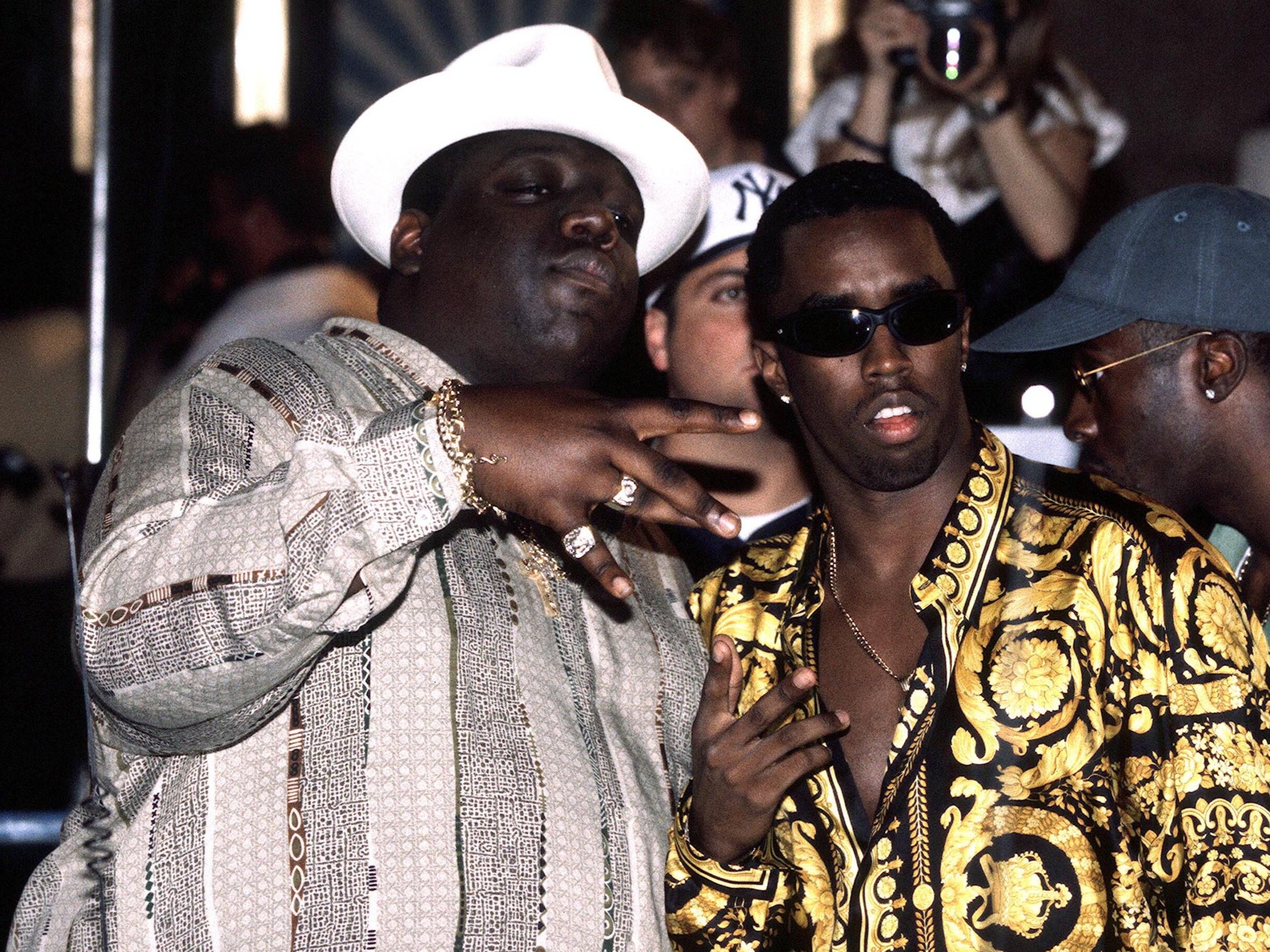

Despite the incident, however, Combs’ reputation was exploding – for positive reasons. His 1992 signing of Brooklyn’s Christopher Wallace – better known as The Notorious B.I.G. – proved particularly momentous for both men’s trajectories. Uptown’s distributor, MCA Records, baulked at releasing Biggie’s debut album, which featured gritty songs about street life – and Harrell, forced to make a decision, cut Combs loose.

“I didn’t want to sit there and be the one confining Puff because the corporation was [telling] me to do that,” Harrell, who died four years ago, told theWall Street Journal in 2014. “I’m not built that way. I told Puff he needs to go and create his own opportunity: ‘You’re red-hot right now. I’m really letting you go so you can get rich.’”

Combs ran with it, creating his own company, Bad Boy Records, and in 1994 releasing Wallace’s Ready to Die. His in-house production team was called The Hitmen. But all of those monikers would soon prove horrifyingly prescient amidst the East Coast-West Coast rap feud.

Bad Boy and Combs were involved in a rivalry with LA-based Death Row Records, a label founded a few years earlier by Suge Knight which was riding Tupac Shakur’s wave of fame in 1994 when the artist was shot five times in New York during a robbery. Shakur claimedCombs and Wallace had prior knowledge of the planned attack, they denied responsibility, but the feud is widely attributed to the unsolved deaths of both the Death Row artist – who was later fatally shot in Las Vegas in 1996 – and Wallace, who was killed six months later in a Los Angeles drive-by. That night, Combs had left the same party as Biggie in a second car; the feud, the murders and any potential connections to Diddy remain conspiracy theory fodder to this day.

Solo career and Bad Boy behavior

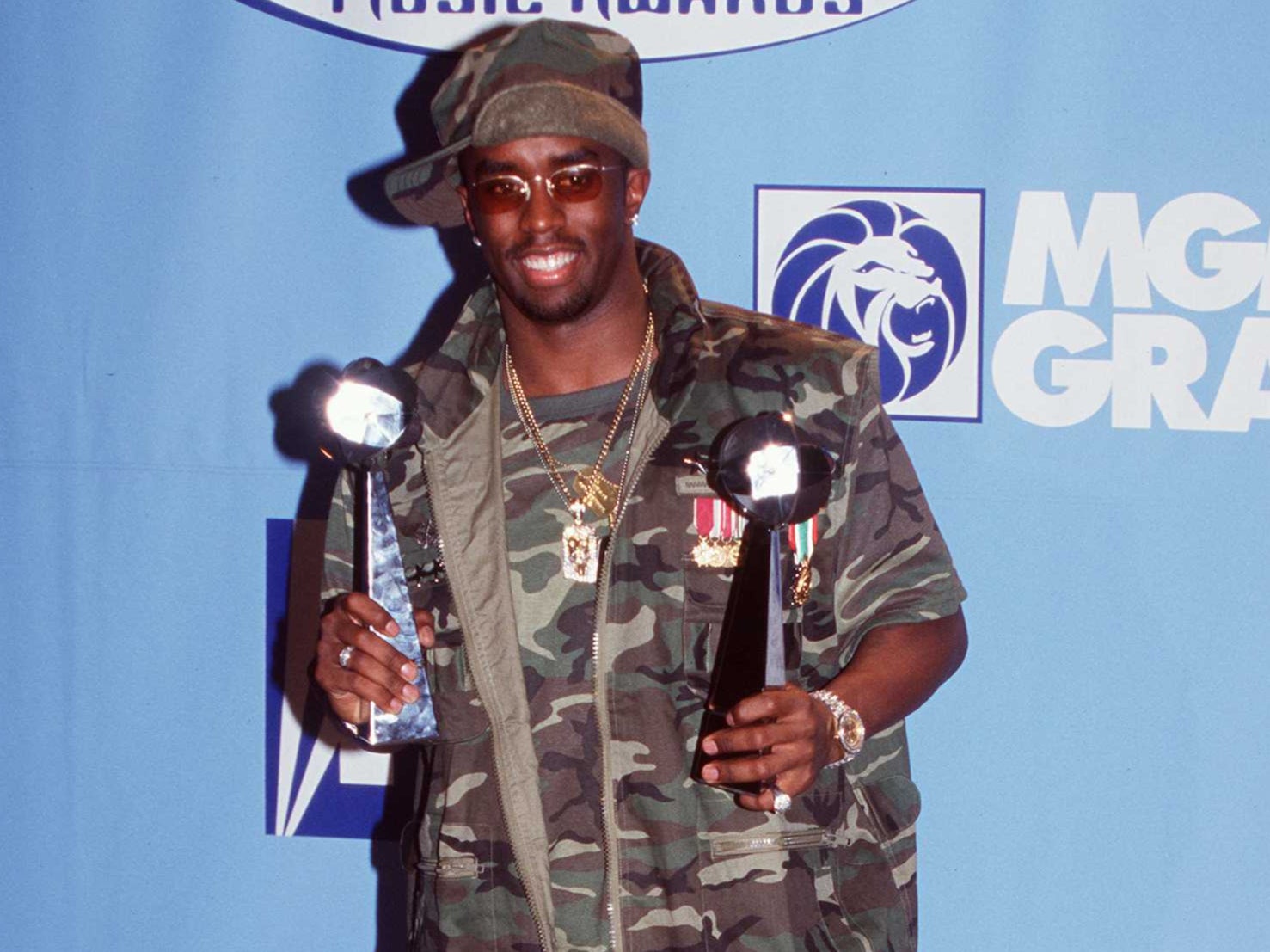

Smack in between both murders, however, Combs released his first single in January 1997 under the name Puff Daddy, followed by his album release that July. It included the Wallace tribute I’ll Be Missing You, which sampled the Police and became the first rap single to debut at number one on the Billboard Hot 100.

Both his personal and professional lives were growing and diversifying exponentially. In 1997 he opened Justin’s, his first restaurant in New York, named for the son he and girlfriend Misa Hylton had welcomed four years earlier before they split. Combs went on to date model Kim Porter, who gave birth to his second son, Christian – who now goes by King – in 1998, the same year, he launched fashion line Sean John. He was nominated for five Grammys that year, and his wealth began snowballing, with Bad Boy generating $130million.

He bought a mansion in the Hamptons that year, too, throwing a Labor Day White Party which quickly became annual fixture for the rich and sexy. (Years later, Paris Hilton – in her trademark bored drawl – remembered the first event with words that echoed those of his college admirers: ‘It was iconic and everyone was there,” she told The Hollywood Reporter)

As Diddy established himself as a true business and social force, however, the behaviour that earned him his nickname continued to rear its ugly head.

In 1999, Combs was arrested on felony charges of assault and criminal mischief after beating up an Interscope Records executive during business hours at the offices of Universal Music, leaving the victim with a broken arm, broken jaw and head wounds. The rapper pleaded guilty to a lesser harassment violation and was ordered to attend a one-day class in anger management.

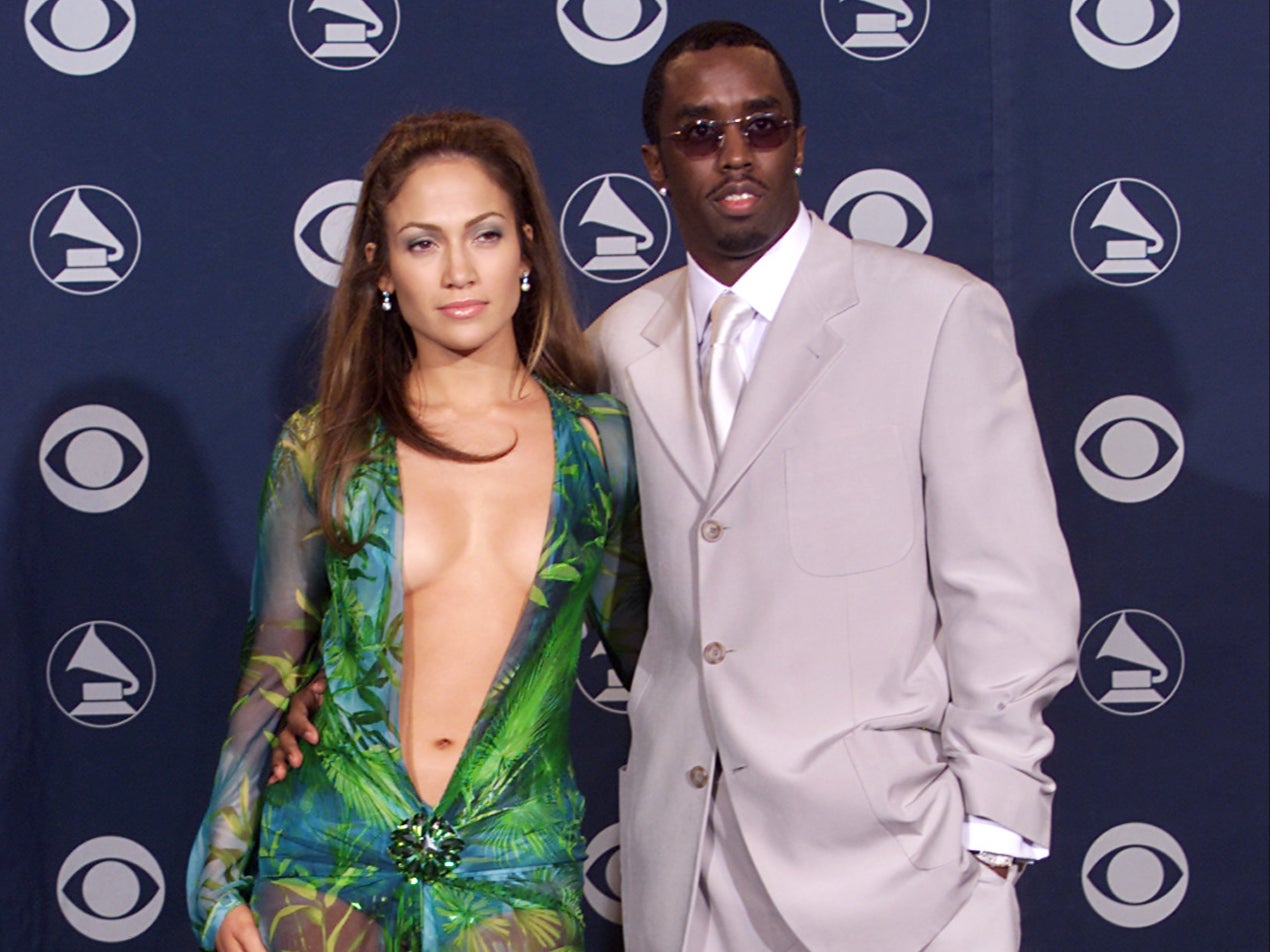

It didn’t seem to do too much, though; three months later, in one of the more serious and high-profile incidents of his career – and that’s saying a lot – Combs was involved in a Manhattan nightclub shooting while in the company of none other than Jennifer Lopez, whom he’d begun dating earlier that year.

The couple had been celebrating at Times Square hotspot Club New York when another patron allegedly insulted Combs and threatened his protege, rapper Shyne. A dispute ensued, shots were fired and three bystanders were injured, including a woman who was shot in the face. Combs fled in a Lincoln Navigator with J.Lo, his bodyguard and his driver – along with a stolen gun none of them had a licence for, as cops found out when they stopped the car.

Combs was found not guilty in March 2001 of four counts of illegal possession of a gun and one count of bribery after a trial that doubled as a media spectacle. Proving what a force the rapper had become, fans turned up at the courthouse for seven weeks, and workers at the building – upon his acquittal – threw open the windows to chant his name and “Leave him alone.”

Combs – who’d been visibly shaking as the verdict was read – publicly thanked God upon his acquittal and reportedly went to church.

The Diddy era

Seemingly keen to distance himself from the Bad Boy image, Combs changed his name to P. Diddy just weeks after walking free from court.

“When I changed names, I put periods on those eras,” he told Vanity Fair in 2021, calling the Puff Daddy era this young, brash, bold hip-hop, unapologetic swagger on a million and just fearlessness

He released the album The Saga Continues in July but continued pursuing new avenues. He appeared in two movies as an actor in 2001, including Monster’s Ball, which won Halle Berry an Oscar. He also began producing new artists and pushing into reality television.

“I have always worked hard – harder than anyone else,” he would later tell Forbes.

By 2002, he was bragging about taking his 14th flight on the Concorde and nominated for menswear designer of the year by the Council of Fashion Designers of America. But even his wildly successful Sean Jean was not free from legal issues, weathering Honduran sweatshop allegations the following year.

That didn’t stop him, however, from performing at the Super Bowl in 2004 or starting the famed Vote or Die campaign around the presidential election. Combs’ tentacles remained everywhere. He decided, however, to drop the “P.” from his name; fans didn’t know what to call him, and he was now just Diddy.

Kim Porter gave birth to their twins in 2006, five months after another long-time friend gave birth to his daughter Chance. Porter called the overlap a betrayal and ended the long-term, on-again-off-again relationship she’d had with the mogul.

Around the same time, however, Combs was finessing the career of singer Casandra Ventura, whom he’d signed to his label in 2005 – and whose bombshell lawsuit in November alleging rape, abuse and sex trafficking brought a world of unwanted attention to the rapper’s door. The pair met when she was 19 and he was 37, and, for years, Cassie was seen as the only woman in his life – the pair’s split in 2018 sparking a headline frenzy.

Combs’ own behaviour yet again landed him in hot water, though; eight months after his 2014 Howard commencement speech, TMZ reported that he’d punched Drake in a Miami nightclub because of a feud over a song.

Six months later, he was arrested and charged in California with three counts of assault with a deadly weapon, one count of making terrorist threats and one count of battery – after allegedly attacking one of his son’s football coaches at UCLA. The assault reportedly involved a kettle bell, but prosecutors ultimately decided not to pursue felony charges.

Time for Love

Perhaps the return of his juvenile “huff” tendencies prompted some introspection, because Combs, by 2017, was considering another name change. He first announced he’d be going by “Love” or “Brother Love,” then repeatedly changed his mind about it until 2021, when he shared a picture on social media of a driver’s licence listing “Love” as his middle name.

“Love is a mission,” Combs vaguely told Vanity Fair a few months later. “I feel like that’s one of the biggest missions that will actually shift things. But besides that, we – the world – is different. We have the internet, we have the power, we have a culture, I have us on a five-year plan.”

It’s unclear what that five-year plan may have been, though it likely didn’t involve the myriad negative – and mournful – developments in Combs’ life. In 2018, Kim Porter, mother of three of his children, was found dead in her Los Angeles home at the age of 47; the coroner later ruled that she died of pneumonia.

“For the last three days I’ve been trying to wake up out of this nightmare,” Diddy posted after her November 2018 death. “ But I haven’t. I don’t know what I’m going to do without you baby. I miss you so much.

“Today I’m going to pay tribute to you, I’m going to try and find the words to explain our unexplainable relationship. We were more than best friends, we were more than soulmates. WE WERE SOME OTHER SHIT!! And I miss you so much. Super Black Love.”

Four years later, he named his seventh child exactly that – Love. In December 2022, announced on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, that he’d welcomed a daughter: Love Sean Combs. The identity of her mother was later revealed to be model and cybersecurity specialist Dana Tran, who is 25 years Combs’ junior.

Shortly afterwards, Combs’ relationships with women – including another much younger one – would be put under a harsh microscope. Five years and three months after the publication of his “five-year plan” Vanity Fair interview – in which Combs volunteered that the #MeToo movement “inspired me” and “showed me that you can get maximum change” – he was hit with three lawsuits in a week alleging sexual assault.

Among the November 2023 suits was Cassie’s, which he settled in a day for an undisclosed sum. The other allegations dated back further, to the days of Combss star ascent in the early 1990s. The suits were filed before the expiration of New York’s Adult Survivors Act, which provided a one-year window for the pursuit of litigation, regardless of when the abuse occurred.

Combs’ legal team dismissed the suits as money grabs and denied all allegations, but it turned out that the rapper’s legal woes were far from over.

A former employee of Combs’, Rodney ‘Lil Rod’ Jones, filed a lawsuit in February that accused him of sexual harassments and threats.

Weeks later, federal agents raided Combs’ homes in Los Angeles and Miami; Homeland Security Investigations New York said the actions were part of an ongoing investigation but did not elaborate. No criminal charges have been filed against Combs, whose lawyers called the raids a “gross overuse of military level force.”

One associate has been arrested on drug charges, and a stone-faced Diddy has since been pictured in Miami – as the rumour mill goes into overdrive. He’s faced and escaped prison time repeatedly before, but the possibility clearly rattles him, as evidenced by his physical shaking in a New York court 23 years ago before his acquittal on multiple charges.

This May, CCTV shocking footage obtained by CNN appeared to corroborate Cassie’s original complaint against Combs. The video from March 2016 showed Combs chasing her down the corridor of a Los Angeles hotel and proceeding to punch and kick her outside a set of elevators.

Combs, wearing only a towel around his waist and a pair of socks, then attempts to drag Ventura back down the corridor.

The rapper later apologised in a social media post and called his behaviour “inexcusable” and said he “takes full responsibility for his actions in the video”. He referred to the incident as “one of the darkest times in his life”, saying that he was “f***ed up” and is “disgusted by his actions”.

Combs added he “asked God for his mercy and grace” and claimed he sought professional help and went to therapy and rehab in the aftermath of the 2016 incident.

“It’s so difficult to reflect on the darkest times in your life, but sometimes you got to do that,” he said. ”I was f***ed up – I hit rock bottom – but I make no excuses. My behaviour on that video is inexcusable.”

“Don’t be afraid to close your eyes and dream,” Combs told Howard students near the end of his 2014 commencement speech, quoting an adage from his “Uncle Shrimp.”

“But then open your eyes and see.”

Now Combs, and the world, wait to see what lies in the master of reinvention’s dubious legal future – and what will become of the dreams that took him this far.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks