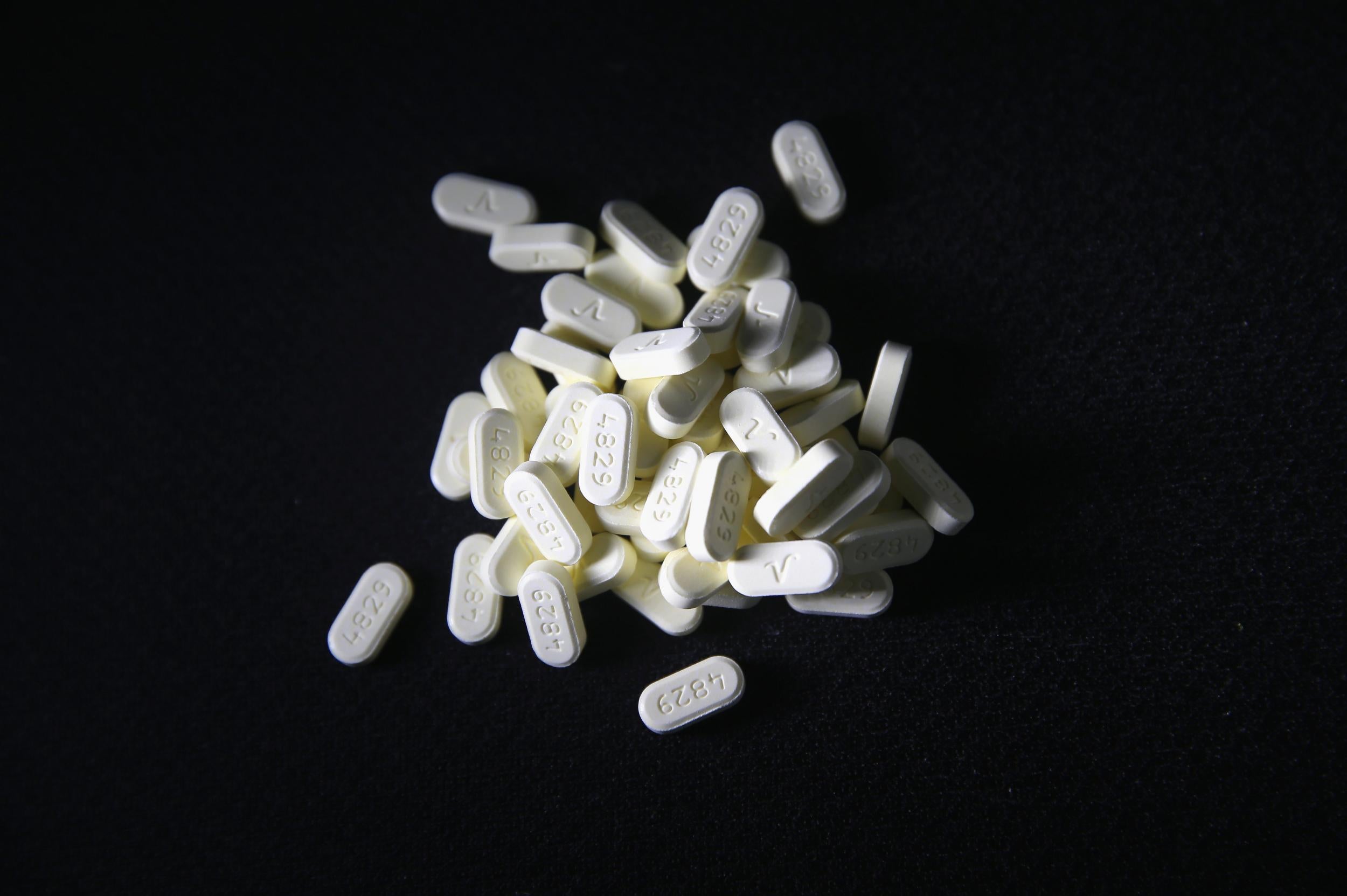

Opioid crisis costs about to skyrocket after $1 trillion in economic damage so far this century

Meanwhile, another new report suggests the pharmaceutical industry has been spending millions to boost opioid prescriptions

The opioid crisis in the United States has cost the economy $1 trillion since 2001, and things do not look like they will get better any time soon.

A new report from Altarum, a nonprofit group that studies the health economy, has found those incredible costs and suggests that the epidemic will cost the US economy an additional $500bn over the next three years as the country sees skyrocketing death rates related to the drugs.

The study finds that the greatest financial costs result from lost earnings due to losses in productivity from young Americans who would otherwise be in their prime working years, but have been hampered by substance abuse disorders, creating a cascading effect that damages local, state, and federal government tax revenues.

“Far and away the largest driver is the loss [in the] productivity and earnings category. That’s driven primarily by those passing away prematurely from opioid overdoses,” Corey Ryan, a senior analyst at Altarum’s Center for Value in Health, told The Independent.

We’re projecting “an acceleration,” Mr Ryan continued. “I would describe that estimate as a case scenario under current policy and current growth rate.”

The report also shows that health care related expenses related to opioids have cost quite a bit of money. Since 2001, medical expenses including emergency room visits, ambulance costs, and the use of the life-saving anti-overdose drug naloxone have cost roughly $215bn, the report finds.

The new report is not the first time the economic costs have been detailed, and not all estimates agree. The White House Council of Economic Advisers has ascribed a much higher cost of the epidemic, for instance, with the cost topping out at $504bn in 2015, up from an estimate of $78.5 billion in 2013. Meanwhile, a recent study conducted by Princeton University’s Alan Kruger, estimated that 20 per cent of the reduction in male workforce participation is due to opioid misuse.

President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency in October, freeing up some further resources for treatment to combat the epidemic. More recently, the Trump administration is seeking $17bn in federal dollars as a part of the 2019 budget to combat the crisis, including coverage for medication-assisted therapy for opioid use disorders through state Medicaid programmes.

“We are currently dealing with the worst drug crisis in American history,” Mr Trump said in October, before adding, “it’s just been so long in the making. Addressing it will require all of our effort.”

“We can be the generation that ends the opioid epidemic,” he continued.

The opioid crisis has been fuelled by what many have described as an over-prescription of the drugs to help manage pain, including chronic pain. A survey of Americans in 2015 determined that nearly two in five had used the drug for pain relief that year, accounting for 92 million US adults.

That prescription rate has resulted from a decades-long effort by prescription drug companies for their products to be given out for pain management. That effort started in the 1990s, when doctors became aware of the burdens of pain, and was fuelled in part by misleading marketing about the safety and efficacy of opioids.

A recent report made public by members of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee has found that the pharmaceutical industry has given millions of dollars to third-party advocacy organisations that then engaged in pro-opioid advocacy, including through the release of guidances that minded the risks of opioid use for long-term chronic pain.

The report, commissioned by the top-ranking Democrat on the committee, Sen Claire McCaskill, argued that the pro-opioid advocacy efforts were conducted in spite of growing bodies of evidence suggesting the dangers of the drug.

“The pharmaceutical industry spent a generation downplaying the risks of opioid addiction and trying toe expand their customer base for those incredibly dangerous medications, and this report makes clear they made investments in third-party organizations that could further those goals,” Ms McCaskill said in a statement accompanying the release of the report. “These financial relationships were insidious, lacked transparency, and are one of many factors that have resulted in arguably the most deadly drug epidemic in American history.”

In addition to that outside spending — some of which may be obscured because some outside advocacy groups are not required to reveal the source of their donations — the pharmaceutical industry has donated millions of dollars to political candidates, and millions more lobbying the federal government every year.

The industry donated a record $42.7m to candidates — Republican and Democrat — in 2016, and spent $277.8m lobbying the federal government in 2017, according to data from the Centre for Responsive Politics.

Mr Ryan said that the incredible costs to the economy projected by his organisation in the coming years could still be curbed through policy and treatment changes to help stem the rising rate of opioid fatalities the reached 64,000 deaths in 2016.

If the crisis is not addressed, however, the costs could be much higher than his organisation’s simple economic impact assessments.

“If you expand that scope, to the societal costs, and the loss of life, and the implicit value of life… the impact on communities and families, in all honesty — the number is much larger than when you look at just the pure economic costs,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks