‘A slow and toxic death’: Opioid crisis victims confront Sackler family with tales of horror at gruelling three-hour hearing

Victims of the opioid crisis stared down the owners of Purdue Pharma and unleashed the pain they suffered over more than 20 years of terror caused by a little white pill called OxyContin

“If you’ve ever heard a newborn in withdrawal, the screaming will haunt you for the rest of your life. And it haunts me.”

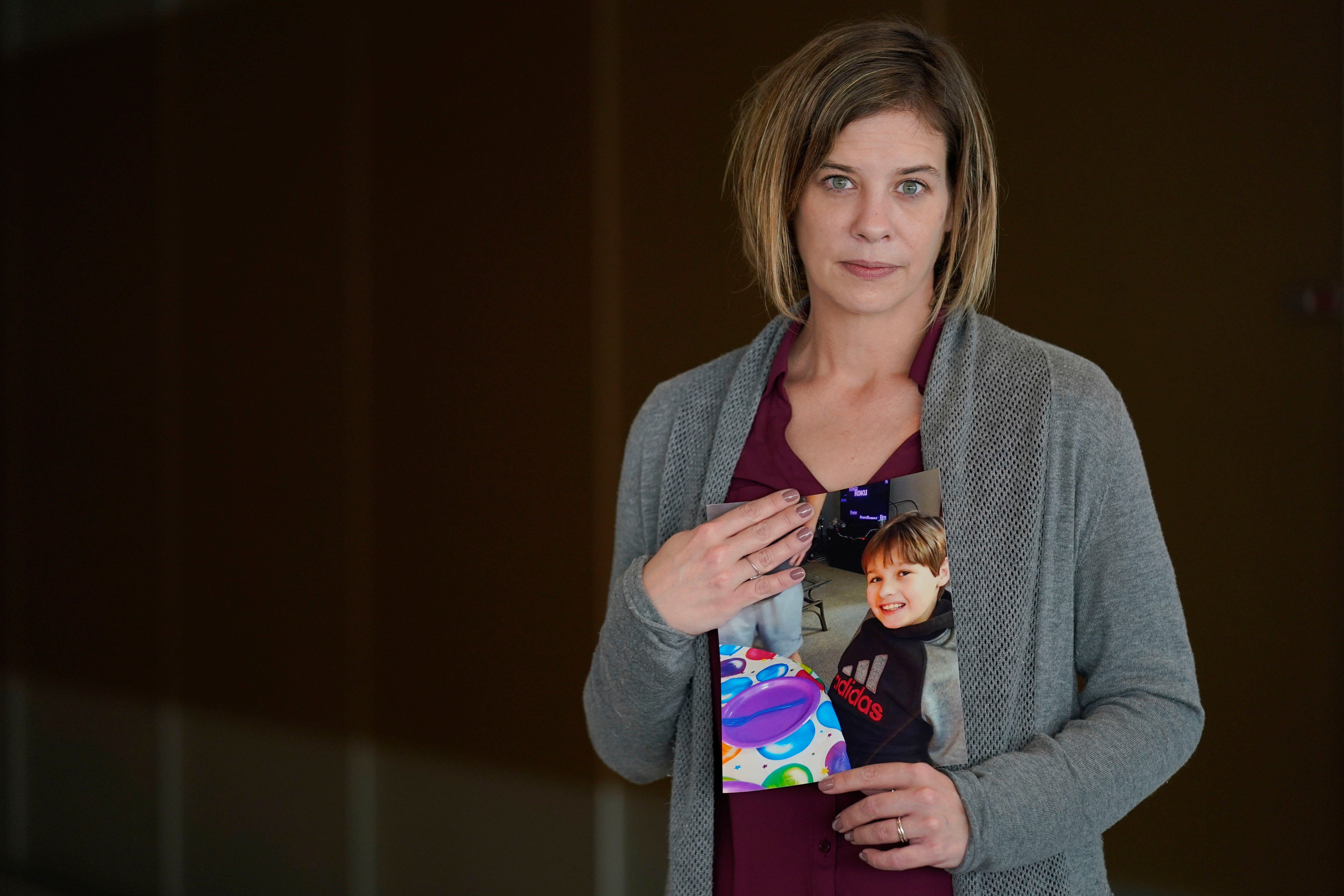

Kara Trainor’s son, born addicted, was robbed of a normal life. Liz Fitzgerald buried one son and then, to her horror, buried another. Keola Maluhia Kekuewa was homeless, tied down in a psychiatric ward and barely survived three suicide attempts.

For over three excruciating hours, 26 victims of the opioid crisis stared down the owners of Purdue Pharma and unleashed more than 20 years of terror caused by a little white pill called OxyContin.

When Ms Trainor was pregnant with her son Riley, doctors assured her there would be no negative outcomes from continuing the prescribed pain medication.

What followed was “awful” and remains with her to this day. While the screams haunt her memories, the struggle of those first six weeks in hospital, when they couldn’t put a diaper on him because of the diarrhoea, continue to this day.

Now 11-years-old, Riley still wears a diaper, is autistic, and needs continual physical and occupational therapy.

“His life has been impacted greatly. He will never graduate high school, he will never go to prom, he will never get married, and I will never have grandchildren,” she said.

“I hope tonight when you reflect on this day you remember what you did to these children.”

The virtual hearing in the US Bankruptcy Court was the first time victims were able to directly address the Sackler family, which says they did nothing wrong and assumes no responsibility for the opioid crisis as part of a $6bn immunity deal.

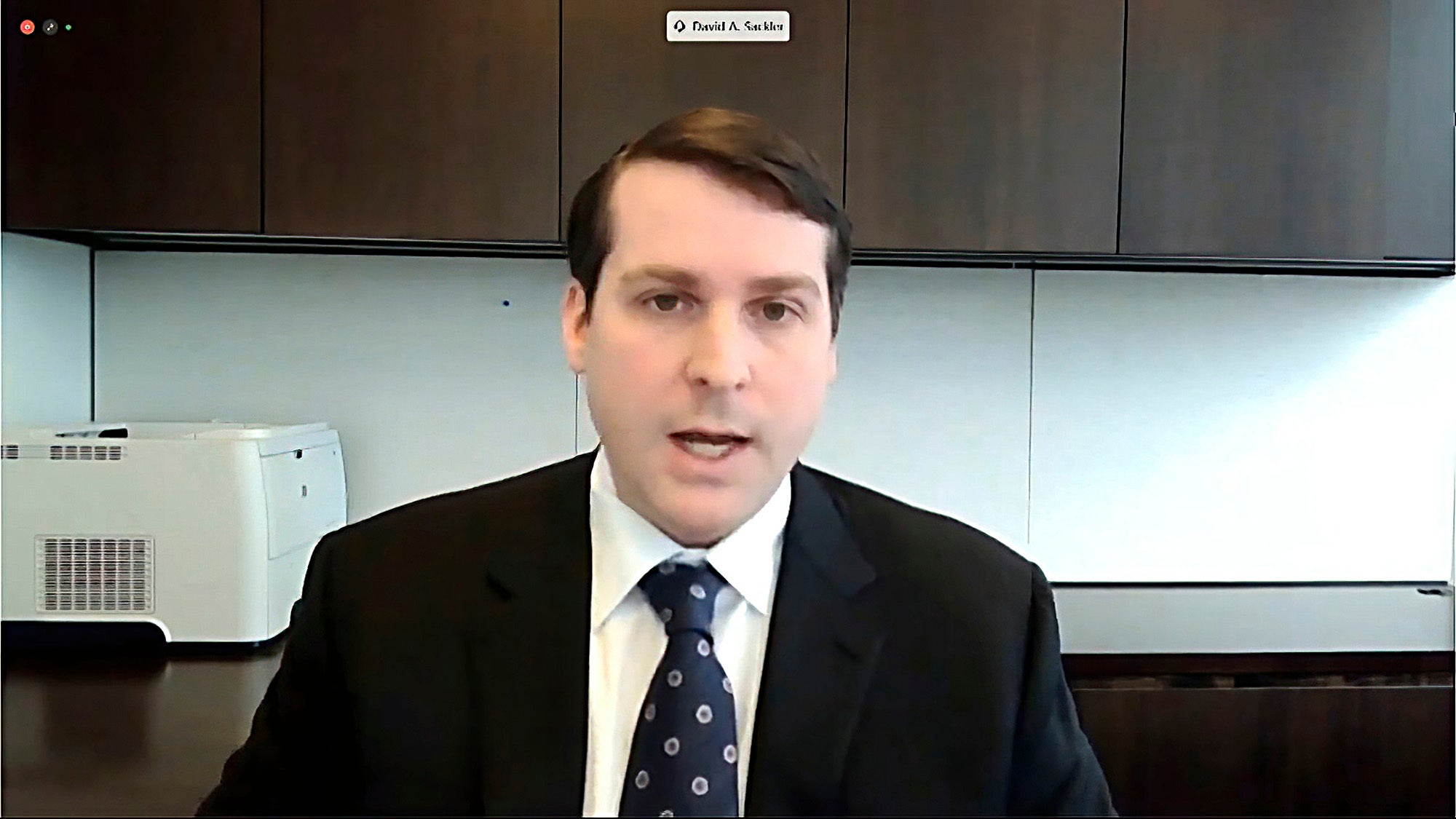

Richard Sackler, former Purdue president and board chair was accused of “hiding” for only appearing via audio. His son, David Sackler, appeared expressionless appearing on video. As did Theresa Sackler, wife of late Mortimer D Sackler, who ran Purdue with brother Raymond Sackler. A third brother, Arthur Sackler, financed the company.

It may be the closest the Sackler family ever comes to facing a public trial for their role in making and marketing Purdue Pharma’s signature painkiller, which helped spark the opioid epidemic that continues more than two decades later.

Lawyers for creditors selected the epidemic’s victims to face the company’s surviving family members, and their stories were brutal.

Shelly Whitaker was prescribed opioids in 2015 after being diagnosed with Lupus. During the pregnancy of her second child a year later, she was assured the drug was safe.

Vomiting, crying, he was “miserable, to say the least”. It wasn’t until her third child, who had to be weaned off with morphine, that she understood what had happened. Her fourth child had the same symptoms.

All three are in therapy. The youngest, in the third grade, can’t read. Her oldest won’t leave his room.

“My poor kids, what had I done,” she said. “I can not go back and change what happened, but I take responsibility for what I did.”

Jenny Scully, a nurse in New York, gave birth in 2014 while on OxyContin and other opioids prescribed years earlier when she was dealing with both breast cancer and injuries from an accident. She was told her baby would be healthy, Scully said, but the little girl has had a lifetime of physical, developmental and emotional difficulties.

“You have destroyed so many lives,” she said, pulling her daughter into view. “Take a good look at this beautiful little girl you robbed of the person she could have been.”

Liz Fitzgerald, a mother of five, lost son Kyle at the age of 25 after a nine-year battle. He was 16-years-old when he has prescribed OxyContin for a knee injury. His brother, Matthew, was introduced to a pill in high school and by the age of 18 the product had “hijacked his brain”.

He lost the battle at age 32. His daughter lost an uncle and then her father.

“She’s left empty and alone and confused. I told her all about you Richard,” said Ms Fitzgerald said.

None of the Sackler family was given an opportunity to respond at the hearing itself. In a statement last week, the family said they have “acted lawfully in all respects”, but expressed regret that OxyContin, “a prescription medicine that continues to help people suffering from chronic pain”, unexpectedly became part of an opioid crisis that brought grief and loss.

“Grief and loss” barely describes what Mark Ferri calls the “equivalent of a slow and toxic death”.

Mr Ferri lost 20 years of a once-productive life after being prescribed opioids for a spinal cord injury in 2001. He lost his home, career path, life savings and his family and friends.

As months turned to years, his dose escalated to 200mg extended-release OxyContin daily with another 100mg of OxyCodone for breakthrough pain. All for acute sciatica and a herniated disc.

“I was no different than a heroin addict. The next surprise was that the drugs were no longer working,” he said.

“I was now a prisoner of the drug … you are existing and no longer living.”

For Keola Maluhia Kekuewa, existing itself has been a two-decade struggle.

Before OxyContin, Mr Kekuewa worked with the Smithsonian and had a beautiful family tenderly attached to generations of family, friends and the ancient Hawaiian culture. After OxyContin, he ended up homeless, livi his nightmare strapped on a gurney in a psych ward, and tried to kill himself three times, the latest in 2018, but woke up with tubes down his throat.

“In shame, I wandered the island,” he said. “I just got an air mattress so I don’t have to sleep on the floor. I never got off opiates.”

The stories spiralled into deeper and darker places. Bill and Kristi Nelson played the 911 call from the fatal overdose of their only son, Brian. The dispatcher asked whether his skin had gone blue; she said it was white. Ms Nelson replays the call in her mind daily.

Ed Bisch’s son Eddie was found dead in bed after a high school party in 2001. It was his 16-year-old sister who found him.

Vicki Bishop was just 19 when she had had her son, Brian, in 1972. They grew up together. In his late 20s, he was given OxyContin after a construction accident.

He became profoundly addicted until it was “a daily burden to feed the monster and keep himself from getting dope sick”.

“This sad lifestyle haunted us,” she said. The haunting ended on Halloween 2017 when he died of an overdose.

Kay Scarpone, the first speaker, lost her son Joseph, a former Marine, a month before his 26th birthday.

“When you created OxyContin, you created so much loss for so many people... I’m outraged that you haven’t owned up to the crisis that you’ve created,” she said.

Janette Adams told of her late husband, Dr Thomas Adams, who was a physician and church deacon in Mississippi and a missionary in Africa and Haiti. He became addicted to opioids after pharmaceutical representatives pitched them, she said. After a terrible decline, he died in 2015.

“I’m angry, I’m pissed, but I move on,” Adams said. “Because our society lost a person who could have made so many more contributions. ... You took so much from us, but we plan to, through our faith in God, move forward.”

Ryan Hampton, of Las Vegas, has been in recovery for seven years after an addiction that began with an OxyContin prescription to treat knee pain led to overdoses and periods of homelessness.

“I hope that every single victim’s face haunts your every waking moment and your sleeping ones, too,” he said.

“You poisoned our lives and had the audacity to blame us for dying,” he added. “I hope you hear our names in your dreams. I hope you hear the screams of the families who find their loved ones dead on the bathroom floor. I hope you hear the sirens. I hope you hear the heart monitor as it beats along with a failing pulse.”

Trent Madison called his father, Scott Madison, from the University of Alabama afraid he was addicted to OxyContin.

“He met me in tears, we wept together,” Mr Madison said. “He said, ‘Dad I’m afraid I’m going to die’. And he did.”

When Mr Madison was 10-years-old, he lost his mother and sister to a drunk driver addicted to alcohol. But, he said, his son was lost to a man addicted to greed.

It’s the greed that Randi Pollock can’t understand, he says. And for the longest time, her family didn’t understand her brother’s addiction either.

He cashed in his life insurance, spent half a million dollars here, half a million there, was getting 10 prescriptions a day, crashed his car three times, ended up in a wheelchair, his bladder failed him, his wife divorced him, and his daughter disavowed him.

“We just thought he was an embarrassment, we didn’t know what this drug was,” Ms Pollock said.

The family grew up in Beverly Hills, so Ms Pollock knows about the money. She gets that part. “I don’t know how anybody could be so greedy,” she said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks