New York's first ever landmark and oldest townhouse is under threat from property developers

The Merchant's House was built in 1832 and the Tredwell family lived there until the youngest daughter died in poverty in the 1930s

Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable once wrote in the New York Times that the Merchant's House Museum was “the real thing”.

“One simply walks through the beautiful doorway into another time and place in New York,” she said.

More than 30 years after that article, and more than 180 years after the house was built, the wooden door, the crescent moon-shaped window and the faux marble interior of the foyer at number 29 East 4th Street remain unchanged - a true time capsule from the mid-19th century.

For Henry James and Edith Wharton fans, the Merchant's House Museum of Manhattan’s lower East Side is the closest they will ever come to experiencing that mysterious, fast-fading vestige of old New York.

Walking through the narrow hallway and into the grand parlor, visitors will learn of the stiff-backed culture where Mr Tredwell went out to do the food shopping as it was not respectable for a woman to be alone, where Mrs Tredwell spent most of her day in a dimly lit room, writing calling cards and receiving guests, and where the servants ran up and down four flights of stairs with scuttles of coal.

The museum, home to more than 40 volunteers and around 15,000 visitors every year, has kept Executive Director Margaret Gardiner busy at the helm for two and a half decades.

Speaking to The Independent, it would be hard to miss the passion and enthusiasm in her voice, but it does not mask her concern about the gargantuan task of maintaining a house built in 1832 - whether it’s the century-old glass panels in the window, the roof, or the “chronic” problem of the water. The neighbouring row houses on East 4th Street were demolished in the 1940s, exposing the museum’s inner walls to the elements.

“Repairs can cost $75,000 one year and $500,000 the next,” she said.

But how long this late-Federal and Greek Revival house stays standing, despite its status as the first ever registered landmark in Manhattan after 1965, is anybody’s guess.

A small information panel on the ground floor informs visitors of the largest threat to the house: the lot next door might soon be turning into an eight-story hotel.

The developers who own the land next door, SRA Architecture + Engineering, have been quiet for two years, and refused to comment on their plans to The Independent.

But if construction goes ahead and if the museum moves even a quarter of an inch, it could cause irreparable damage to the original plasterwork and the whole building itself.

“Protecting the house for damage is our first and foremost priority,” said Ms Gardiner. “And we have been working with engineers to develop protection plans during the construction, for the building and also specifically for the ornamental plasterwork, which is the finest surviving from the period.“

She said it was imperative to preserve not just the building, but also the history of the family that lived there.

The Tredwell family, headed up by hardware merchant Seabury Tredwell, who owned hundreds of acres of farmland in Long Island and who used to race his horse up Broadway, moved into the house in 1835 with his wife Eliza. The couple had eight children.

They lived in the lower East Side house for most of their lives, through the Civil War, until the last remaining daughter Gertrude died, impoverished, at the age of 93, just as builders were constructing the Rockefeller Center.

More than 80 per cent of the furniture, decor and household items in the museum belonged to the family, from the books on how to find a husband to the lace window hangings - designed to keep out the dust and filth from the street - to the orange rococo chairs. More than a century later, the material on the back of those chairs is in perfect condition as they were never touched - ladies always sat up straight when they came to call.

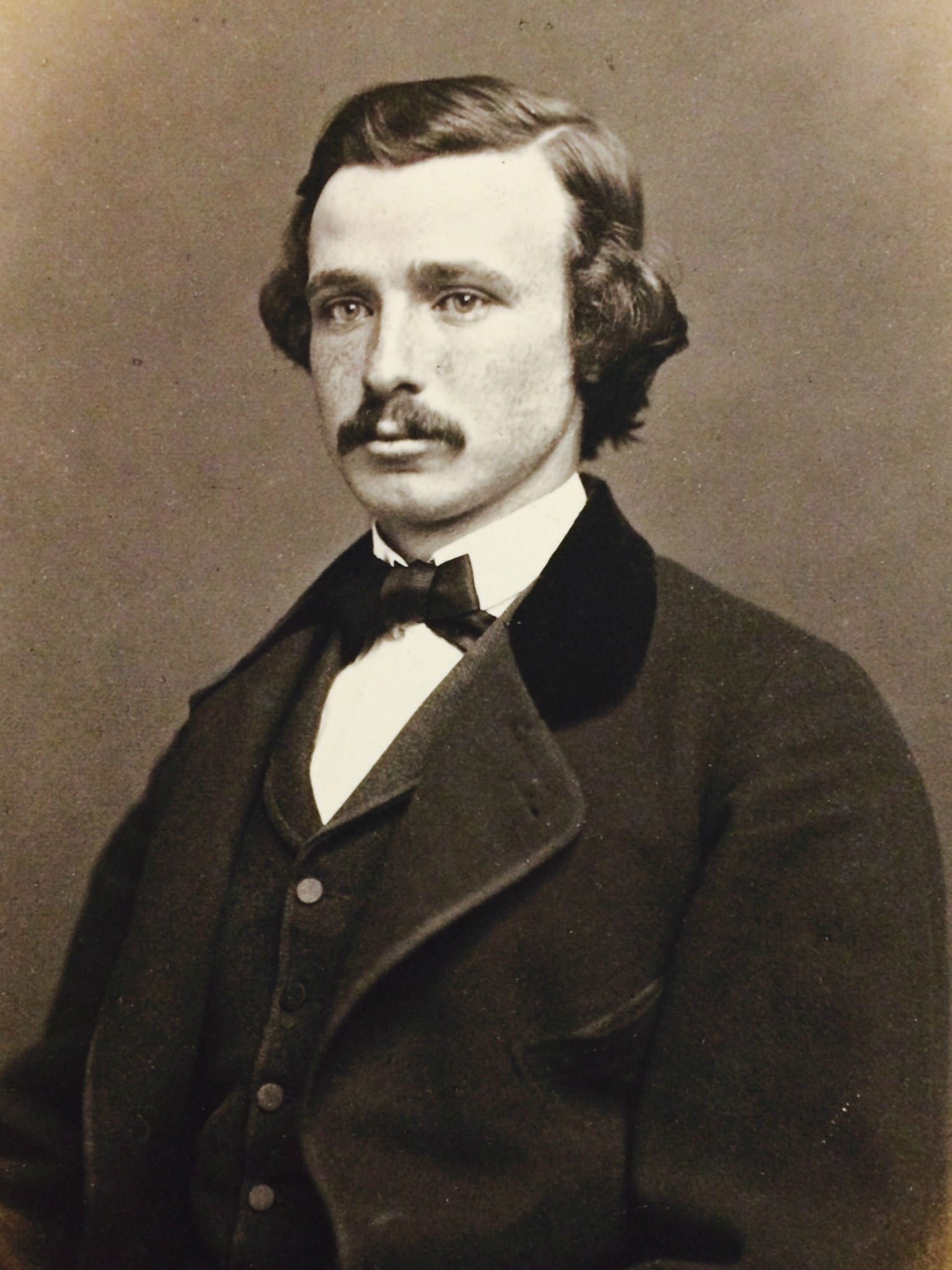

Ms Gardiner said new surprises about the house or the family are always popping up. One enthusiastic volunteer, she said, set out to discover more about a man with whom Gertrude had been in love. The man in question was called Louis Walton and graduated from medical school, but Gertrude’s father forbade the couple to be married.

No one had ever known what he looked like, but with the new information supplied by the volunteer, staff could identify Mr Walton as the man in a photograph that Gertrude had always kept by her side. They both remained unmarried for the rest of their lives.

Work to commemorate the family history continues. In 2012, the museum restored the fourth floor - the servants’ quarters - which were host to an ever-changing roster of Irish women.

“Before, we were only telling half the story. Without these four girls the Tredwell family could not have led the lifestyle they had,” said Ms Gardiner.

Very little is known of these women, except their names, ages, and how long they worked at number 29. Visitors can lift a bucket of coal in the kitchen to get an idea of the physical strain of their daily lives, and they can see the bells that rang, emitting different sounds for each room, ordering them at the family’s beck and call.

Ms Gardiner would like to restore the third floor - currently roped off as staff quarters - to the old children’s bedrooms, but said it came down to a lack of funds.

There are only six living descendants of the Tredwell family. The staff, volunteers and visitors are so fascinated by the limited knowledge they have of its inhabitants that they have created the myth of the family “ghosts” that wander its floors at night.

The Tredwell family remained loyal to their house for a century, refusing to move uptown as the area around them became increasingly unfashionable and even dangerous.

(Edith Wharton’s childhood home, near Madison Square Garden, was said to be the boundary of the fashionable neighbourhood in Manhattan’s mid-19th century. Unlike the beautifully preserved Merchant House, the childhood home of the first female Pulitzer Prize winning author is now a Starbucks and a Weightwatchers office.)

Why the Tredwell family never moved to a more fashionable district remains a mystery to the museum staff.

But just like that family, Ms Gardiner and her team at the Merchant's House Museum are equally determined not to leave.

“There is nothing else really like it here in New York,” she said. “The history is palpable.“

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks