Michael Brown shooting: Angry parents demand justice for their teenage son gunned down by police in Ferguson

The gentle giant was walking down a street as a white officer fired from a police car, says his friend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When he posed for his graduation picture in March, Mike Brown was still just Mike Brown. A student with a football tackle build. Just one of the 100 or so in his senior class at Normandy High, a struggling school that had lost its state accreditation and, along with it, a measure of its pride, in an area already beset by challenges.

In his photo, Brown barely smiled, his green mortarboard tilted back on his large head, a red sash around his shoulders – a slight bravado that, his teacher noted, might have obscured how difficult reaching this moment had been.

Michael Brown officially graduated on 1 August, later than some and months after the photo was taken. He still had credits to earn then. He was in an alternative learning programme, a way to help the students facing the longest academic odds.

But he got his diploma. And 10 days after that, he was to start at a local technical school to learn how to fix furnaces and air conditioners.

“He’d accomplished it,” teacher John Kennedy said. “In the last two months, Mike was there every doggone day and giving it his full effort.” “He was a gentle giant,” said Charles Ewing, Brown’s uncle.

Last Saturday, as Brown walked down a street with a friend, the 18-year-old was fatally shot by a police officer in Ferguson, a working-class suburb north of St Louis. Brown was unarmed.

What happened during the unidentified police officer’s a confrontation with Brown and his friend remains unclear.

County police and the FBI have announced separate investigations. But doubts in the local community about whether the shooting was justified quickly boiled over, leading to days of rallies and unrest, including angry confrontations between protesters and police, nighttime scenes made hazy by tear gas and shouted slogans.

Now Brown is part of a renewed national discussion about how police treat minorities, especially young black men.

President Obama on Tuesday offered his “deepest condolences” to Brown’s family, who is now represented by the same attorney used by the family of Trayvon Martin, the Florida teenager gunned down by a Neighbourhood Watch volunteer in 2012.

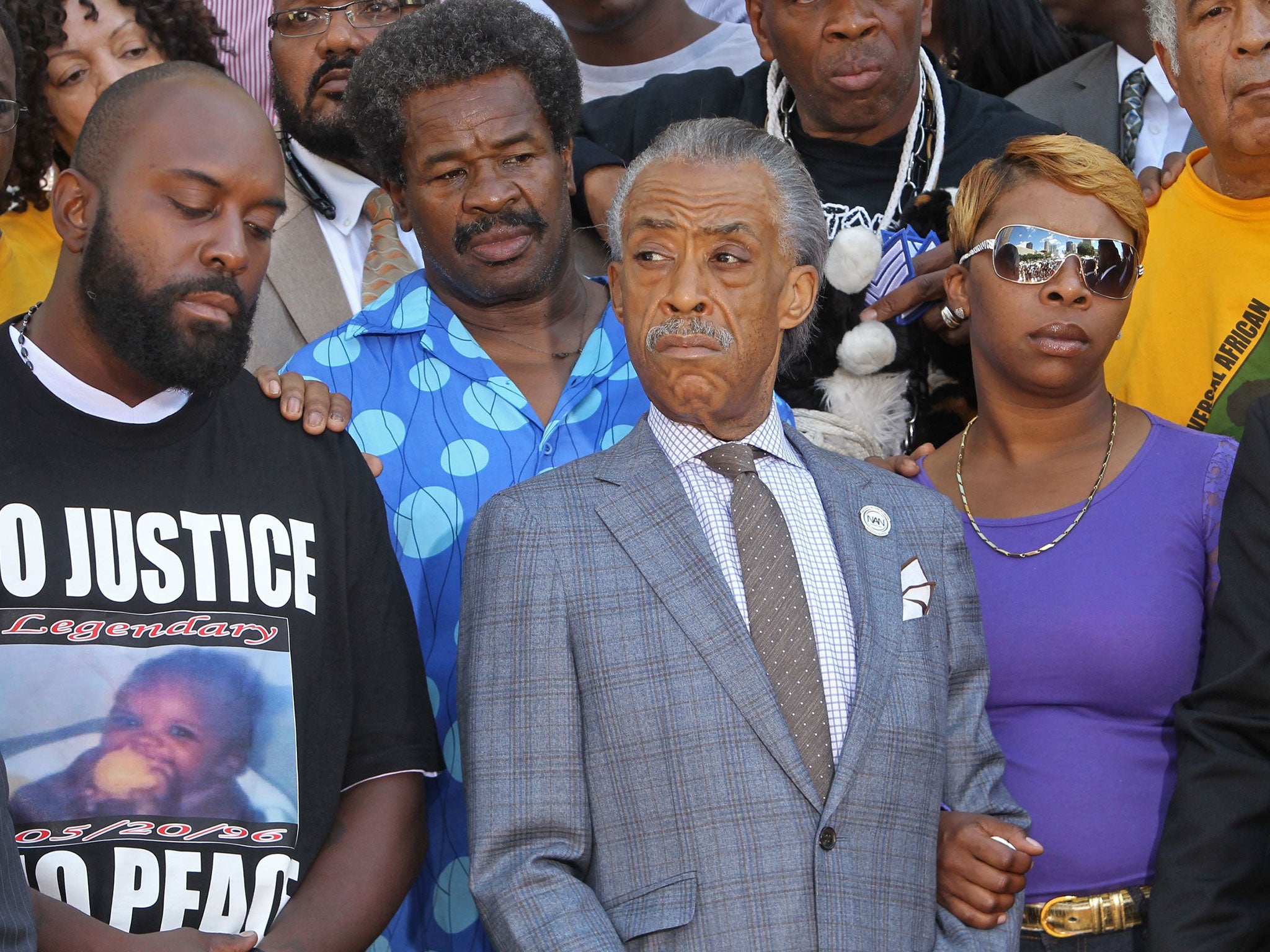

The Rev Al Sharpton came to St Louis; social media and talk shows swirled with anger aimed at both Brown’s death and the violent demonstrations that followed.

On Tuesday night, the authorities in Ferguson braced themselves for another round of violence. Flights were banned from operating below 3,000 feet over the city, at the request of county police. A police spokesman said a helicopter had been shot at multiple times and that the flight ban is “to provide a safe environment for law enforcement activities”. The ban may also preclude the hovering of news helicopters.

The official police investigation, a standard reaction to any officer-involved shooting, was moving slowly, said Brian Schellman, a county police spokesman. Three days after the incident, detectives still had not talked with many “critical witnesses”.

“They’ve reached out to numerous people who have been unwilling or unable to talk with them,” Mr Schellman said.

Police detectives have tried “numerous times” to talk with Dorian Johnson, Brown’s friend who was with him when the shooting occurred and who, since then, has given several press interviews.

While Ferguson police have said Brown pushed the officer as the patrolman was trying to exit his car and then struggled with him over his gun, Johnson has said the officer was the aggressor. The officer, according to Johnson, shot Brown while still inside the vehicle, then emerged and fired multiple times.

“We want to talk to him,” Mr Schellman said. “We have to talk to him.”

Ferguson police had planned to release the name of the officer who shot Brown, but they reversed this decision on Tuesday as “threats [were] being made against all Ferguson officers on social media sites”, the city’s police spokesman, Timothy Zoll, said in an email. There is no timetable for when the officer’s name could be released, he said.

Benjamin Crump, an attorney for Michael Brown’s family, said releasing the officer’s name could help ensure peace on the streets of Ferguson.

In Ferguson, residents with signs gathered at the site of the shooting in the early afternoon, prompting honking horns and cheers of “hands up, don’t shoot”.

In nearby Clayton, several hundred people marched downtown and descended on the county prosecutor’s office. “I need justice for my son,” Michael Brown Sr said to the press on Tuesday.

The town where Brown died has 21,000 residents. The poverty rate is about twice Missouri’s average. There are challenges. But it is also home to the world headquarters of Emerson Electronics, a $24bn company, and Express Scripts, which employs thousands in the St Louis area.

Black residents make up about two-thirds of Ferguson’s population. In the 2000 census, whites held a slim majority. Meanwhile, the city’s police force remains overwhelmingly white.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments