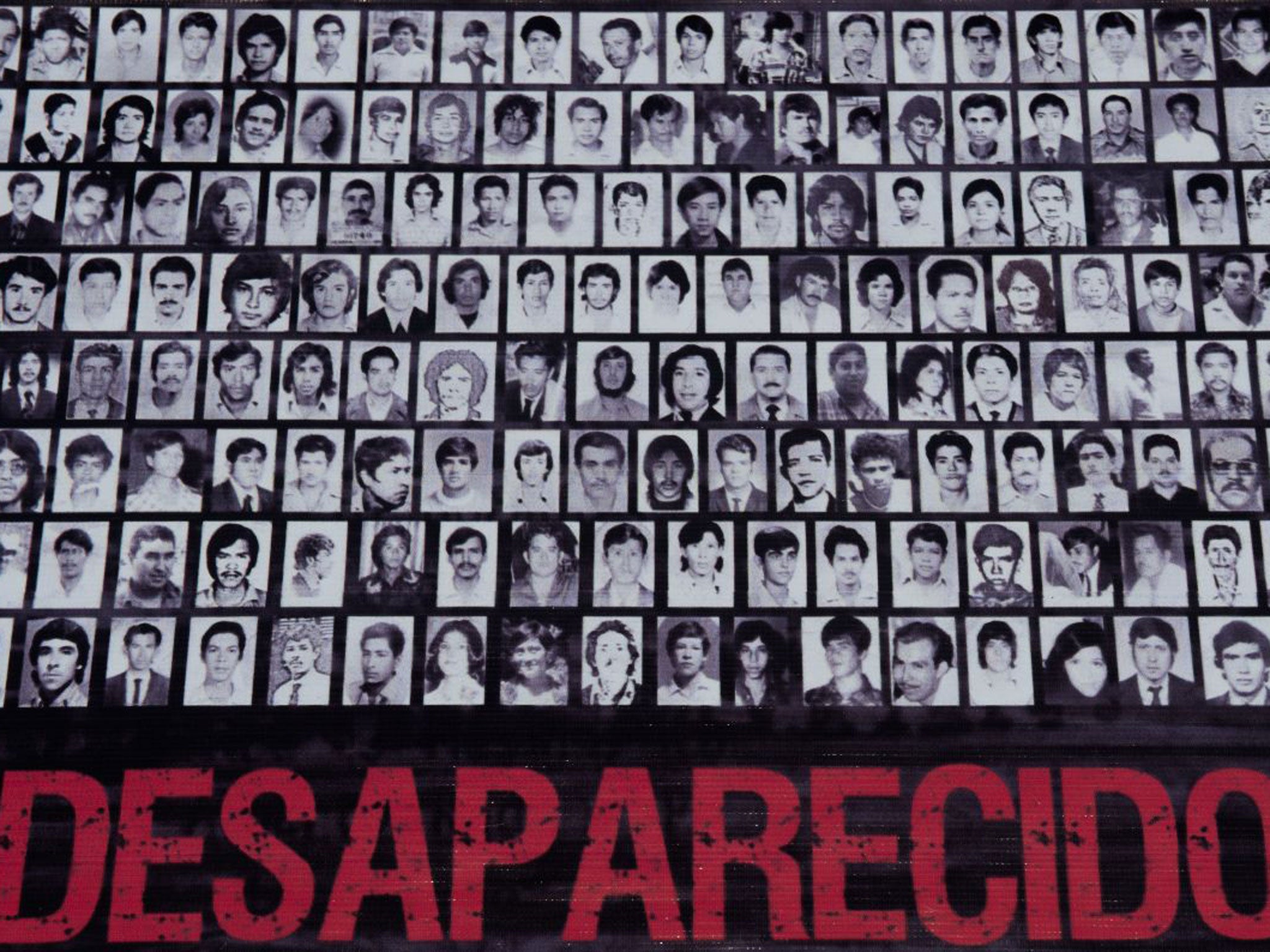

Mexico: More than 25,000 people disappear in six years

Unpublished official figures show cost of chaos and violence enveloping country in fight against drug gangs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mexico's Attorney General has compiled a list showing that more than 25,000 adults and children have gone missing in Mexico in the past six years, according to unpublished government documents.

The data sets, submitted by state prosecutors and vetted by the federal government but never released to the public, chronicle the disappearance of tens of thousands of people in the chaos and violence that have enveloped Mexico during its fight against drug mafias and crime gangs.

Families have been left wondering whether their loved ones are alive or among the more than 100,000 victims of homicides recorded during the presidency of Felipe Calderon, who leaves office today. The names on the list – many more than in previous, non-government estimates – are recorded in columns, along with the dates they disappeared, their ages, the clothes they were wearing, their jobs and a few brief, often chilling, details:

"His wife went to buy medicine and disappeared," reads one typical entry. "The son was addicted to drugs." "Her daughter was forced into a car." "The father was arrested by men wearing uniforms and never seen again."

The documents were provided by bureaucrats frustrated by what they describe as a lack of official transparency and the failure of government agencies to investigate the cases.

The leaked list is not complete – or, probably, precise. Some of the missing may have returned to their homes, and some families may never have reported disappearances.

But the list offers a rare glimpse of the running tally the Mexican government has been keeping, and it confirms what human rights activists and families of the missing have been saying: that Mexico has seen an explosion in the number of such cases and that the government appears to be overwhelmed. "What does the government do? Nothing or almost nothing. Why? There is a paralysis," said Juan Lopez Villanueva of the group United Forces for Our Missing in Mexico. "The state has failed us."

According to the National Commission on Human Rights, more than 7,000 people killed in Mexico in the past six years lie unidentified in morgue freezers or common graves. The commission's numbers suggest the government count might be accurate. From 2006 to mid-2011, the commission notes that more than 18,000 Mexicans were reported missing.

Mr Calderon's spokesman declined to offer a reason why the numbers have not been made public during his tenure, and the Attorney General's office did not respond to questions.

Critics say the outgoing government is burying the numbers because their publication would highlight Mexico's failure to investigate the cases, and undermine efforts by Mr Calderon to show his fight against organised crime is working.

"Releasing the data would add to the already deteriorating forecast about growing insecurity, and publishing such a very large number just reinforces the idea that the country is violent," said Edna Jaime Trevino, director of the think tank Mexico Evalua.

The task of tracking the missing now falls to the incoming President Enrique Pena Nieto's new government. There is no statute of limitations for missing-person cases, and Mexico has heard withering criticism from both the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the United Nations about its handling of them.

In December 2011, Mr Calderon pledged to create a national database including lists of the people who had disappeared and of unidentified bodies, and he promised it would be ready in early 2012.

Then in March, the Mexican Congress passed a law that required the government to establish Mr Calderon's database, which medical examiners, law enforcement officials and families could use to help track cases. Since then, politicians have failed to publish the regulations that would allow the law to be implemented.

State prosecutors agreed to provide data from their missing-person cases to the Attorney General, but their reports appear uneven. For example, prosecutors in the northern border states of Chihuahua and Coahuila report only a few hundred cases, even as the governors of those states have stated that there were many more. Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments