Maryland studies repeal of death penalty

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

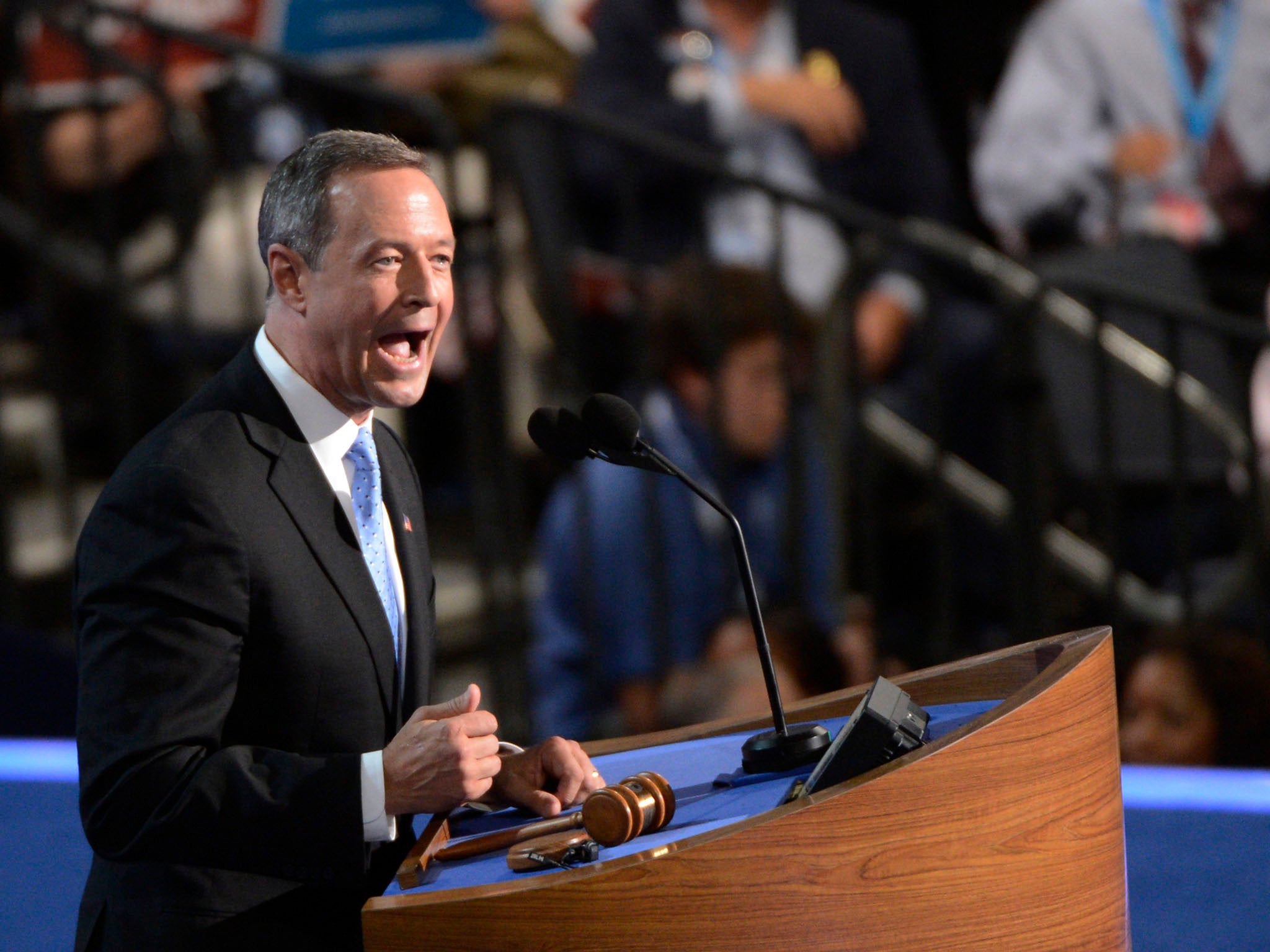

Your support makes all the difference.Coming off some high-profile wins at the ballot box this month, Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley is considering another run at repealing the death penalty when lawmakers reconvene in January, aides say. It's an issue that could add to his progressive legacy.

But even if the law remains on the books, advocates on both sides agree that O'Malley , D, is all but certain to finish his two terms in office without having presided over a single execution of one of the state's five condemned prisoners.

That's largely because O'Malley's administration has yet to implement regulations required for executions to resume, nearly six years after Maryland's highest court halted the use of capital punishment on a technicality. And there's little reason to believe the politically ambitious governor will do so in his remaining two years, as drug shortages and other factors have complicated the mechanics of lethal injection in other states.

"It's legislating by inaction," said Sen. Joseph M. Getty, R, a member of the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee and an O'Malley critic. "I'm among the members of the Maryland General Assembly who would like to see the law followed."

O'Malley declined to be interviewed for this article, and aides said a decision about whether he will sponsor a death penalty repeal bill will be made in coming weeks. Administration officials responsible for drafting the rules needed for executions to resume offered no timetable for when they might be issued.

"We're still working on the regulations, still exploring best practices around the country," said Rick Binetti, a spokesman for the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. "It's a serious issue, and the department is being extra careful, and that's obviously taking some time."

Practices across the country have changed since 2005, when Maryland executed its last prisoner, under the watch of Gov. Robert Ehrlich, R, and those changes could make a return to capital punishment in the Free State even more unlikely.

Most of the largest death-penalty states — Virginia being a notable exception — have moved recently from a three-drug cocktail to a single-drug regimen for executions by lethal injection: administering a larger, lethal dose of the sedative that had been used as the first step in the process.

The one-drug method can take longer to take the life of the prisoner, but it is easier to administer and carries less risk of excruciating pain if something goes wrong. It appears to be "the wave of the future," said Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

Nine of the past 10 executions in the United States have used a single drug, according to the center.

For Maryland to move in that direction, it would take action by more than just O'Malley. Maryland law spells out that lethal injections must involve a combination of at least two drugs. Changing to just one would require both a new law and new regulations.

While it's unclear if there are enough votes to repeal the law altogether, many lawmakers doubt there are enough votes, particularly in the House of Delegates, to adopt a new law that would restart executions.

"I think there's an impasse," said Del. Anne Healey, D, a death penalty foe.

The standstill in Maryland, one of 34 states with a death penalty law, comes as the use of capital punishment has declined across the country in recent years. So far, 40 prisoners have been executed this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Nationally in 2000, there were 85 executions.

While public support for the death penalty has waned, attitudes have not changed nearly as quickly as on same-sex marriage, among the progressive issues O'Malley successfully championed this month at Maryland's ballot box.

That was most evident in California, where voters rejected by about six percentage points an initiative to repeal that state's death penalty and clear the country's largest death row.

In Maryland, the Court of Appeals ruled in December 2006, during Ehrlich's last full month in office, that the state's death penalty procedures had not been properly adopted, halting executions until new regulations were issued by the administration.

O'Malley focused instead on lobbying the legislature to repeal the death penalty. In high-profile testimony shortly after he took office in 2007, the governor, a Catholic, argued that capital punishment is "inherently unjust," does not serve as a deterrent to murder and uses resources that could be better used to prevent crime.

It was not until July of 2009, after the legislature balked at repealing the death penalty for the third year in a row, that O'Malley's administration proposed regulations that would allow executions to resume.

Those regulations were later withdrawn after a legislative review panel raised numerous questions about them. Revised regulations have not been issued since.

The bottleneck to repeal efforts in the legislature in recent years had been the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee, whose members have broken 6 to 5 in favor of keeping the existing law. That has prevented the legislation from reaching the full Senate, where repeal advocates now say they stand a good chance of winning a majority vote.

A repeal bill last reached the Senate floor in 2009, when Senate President Thomas Mike Miller, D, allowed debate as a courtesy to O'Malley. Rather than pass the bill, the Senate amended it to tighten evidentiary standards in capital cases but to keep the death penalty on the books.

Sen. Robert A. Zirkin, D, considered a potential swing vote on the Judicial Proceedings Committee, said he remains fine with the 2009 compromise, which he said limits the chances of an innocent person being executed.

Under that law, the death penalty is an option only in cases that include at least one of three types of evidence: DNA or biological evidence; a videotaped confession; or a videotape linking the suspect to the crime.

"I respect people who find the death penalty immoral. I'm not one of those people," Zirkin said. "I think if the law exists, it should be utilized."

Still, anti-death penalty advocates believe the coming year holds promise.

"I think there's a lot of momentum for it," said Jane Henderson, executive director of Maryland Citizens Against State Executions. "If it's going to happen while O'Malley's still governor, this will be the year to do it."

Coming off wins this month on ballot measures allowing same-sex marriage and extending in-state tuition rates to illegal immigrants, O'Malley might feel emboldened to try to push through one more progressive measure, some political observers say.

But others caution that the repeal of the death penalty is a mixed bag for a politician with national aspirations. Democrats in some early presidential nominating states still support capital punishment in significant numbers, they note.

"If he sees an opening, I think he'll go for it," said Mike Morrill, a veteran Democratic strategist. "But it would be a matter of conscience, not politics. And it may be that the status quo is enough to meet his values."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments