Marsha P Johnson: ‘America’s first transgender statue’ will immortalise Stonewall riots veteran

City announces monument during Pride month to commemorate iconic activists

The “P” in Marsha P Johnson stood for “Pay it no mind” – and when people got too nosy about her, that is what she would tell them. Pay it no mind.

Friends say the world heeded that advice, giving Johnson – a transgender activist who played a vital role in the Stonewall riots and the gay rights movement it launched – far less attention than she deserved.

Now that’s finally changing.

As New York prepares to mark the 50th anniversary of Stonewall alongside its Pride celebration, the city announced plans to build a statue honouring Johnson and her friend Sylvia Rivera, who also championed LGBT+ rights.

It will be the first permanent, public monument honouring transgender women in the world.

“The city Marsha and Sylvia called home will honour their legacy and tell their stories for generations to come,” said New York City first lady Chirlane McCray.

Johnson was born in 1945 and raised in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

In a 1992 interview, she said she started wearing dresses at the age of five, but stopped after being teased.

As soon as she graduated from high school, she went to New York with a bag of clothes and $15, she said.

Although Greenwich Village was one of the most tolerant places for LGBT+ people at the time, police frequently harassed anyone who didn’t conform to sexual norms.

There was no way someone like Johnson could get or keep a job. So, like a lot of gay, lesbian and transgender people at the time, she was frequently homeless and worked as a prostitute.

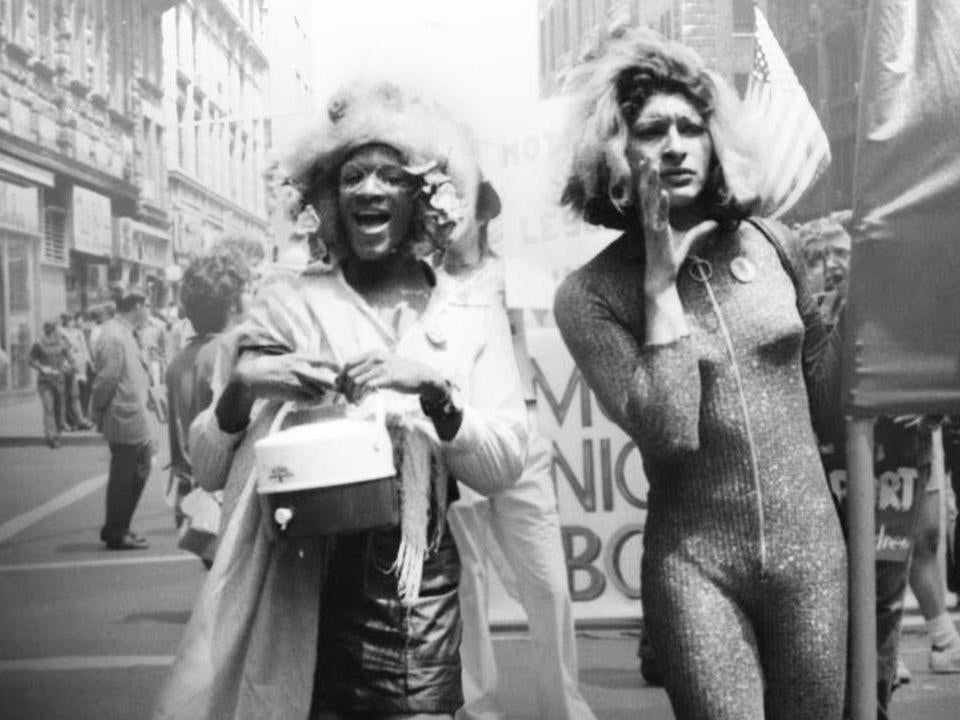

Despite these hard circumstances, Johnson was known for her open and optimistic personality. She dressed in flashy, homemade outfits, and bedecked her hair in flowers, fruit and even Christmas lights.

“I was no one, nobody from Nowheresville, until I became a drag queen,” she said.

The word “transgender”, which describes people whose gender identity does not correspond to their birth sex, was not in use at the time.

Johnson referred to herself using female pronouns, and at times described herself as “gay”, a “queen”, a “drag queen”, and a “transvestite”.

She also had a religious streak. She was often seen praying for friends in neighbourhood churches, and said she would never get married because Jesus “is the only man I could really trust...he listens to all my problems, and he never laughed at me.”

In the 2012 documentary Pay It No Mind: The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson, Stonewall veteran Agosto Machado said: “Marsha always gave this blessed presence and encouragement to be who you wanted to be.”

Longtime friend Randy Wicker added: “Friends and many people who knew Marsha called her ‘Saint Marsha’, because she was so generous."

Sylvia Rivera even credited Johnson with saving her life – a life marked by hellish trials from the beginning.

Her father abandoned her at birth, and her mother killed herself when she was three.

As a child, Rivera would try on her grandmother’s clothes and makeup, and was beaten when caught. By 11, she was a runaway and child prostitute.

She met Johnson on the streets in 1963, when she was still a preteen.

“She was like a mother to me,” Rivera said later. Johnson gave her a measure of stability and love she had never experienced.

There are many stories about what Johnson and Rivera did in the early morning hours of 28 June 1969, when the Stonewall riots erupted.

Almost everyone agrees they were there. One legend has Johnson throwing the first “shot glass heard around the world”; another has her throwing the first brick.

Stonewall historian David Carter concluded it was “extremely likely” that Johnson was among the first people to resist the police.

But in 1987, Johnson herself told historian Eric Marcus that she didn’t arrive until “the riots had already started”.

And in 2001, Rivera said she was at the Stonewall Inn with a boyfriend when it was raided, but that she wasn’t the first to resist.

In his book, The Gay Metropolis, Charles Kaiser suggested the first person to physically resist may have been a lesbian named Stormé DeLarverie, who died in 2014.

In a 2018 essay, transgender poet Chrysanthemum Tran said the particulars of who-did-what don’t matter.

Stonewall was a “collective uprising”, and Johnson and Rivera should be acknowledged not just for their actions on those few days, “but for their lifelong work of organising and activism”.

In the wake of the riots, the pair were frequent organisers and participants at gay rights protests.

They also founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, and opened a house to shelter homeless LGBT+ youth – the first shelter of its kind in the country.

But as the gay rights movement grew, some wanted people like Johnson and Rivera pushed out.

Some gay and lesbian activists took the tack that they were no different than their straight peers, and thought that argument was harder to make if Johnson showed up in plastic heels and fruit in her hair.

Things came to a head at the Pride March in 1973, when Rivera said she was repeatedly blocked from speaking.

When she finally took the microphone, she shouted: “If it wasn’t for the drag queen, there would be no gay liberation movement. We’re the front-liners.” She was booed off the stage.

After the speech, Rivera attempted suicide, she said; Johnson found her and saved her life.

Rivera left activism and New York after the incident, but Johnson stayed.

In the mid-1970s, Andy Warhol made her the subject of one of his famous silkscreen portraits.

She also began performing in a drag revue called the Hot Peaches. In 1980, her housing situation finally stabilised when Wicker took her on as a roommate.

As the AIDS crisis devastated the LGBT+ community in the 1980s, Johnson continued her work, marching with activist group ACT UP, helping at fundraisers, and nursing her friends on their death beds.

Johnson’s body was found floating in the Hudson River on 6 July 1992.

Her death was quickly ruled a suicide, but after protests, the cause was changed to an unexplained drowning.

Johnson was repeatedly the victim of violent attacks, and many close to her think she was murdered. The case was reopened in 2012, and remains open.

Rivera returned to New York after Johnson’s death. She struggled with addiction and lived by the pier where Johnson’s body was found.

But by 2001, she was sober, marching in Pride parades, and living in Transy House, which was created by activists inspired by STAR.

Rivera died of liver cancer in 2002. The Village Voice eulogised her as “the Rosa Parks of the modern transgender movement”. In the last hours of her life, she was urging gay leaders who had come to her bedside to be more inclusive.

Now, as the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots approaches, the search begins for an artist to create a monument to two of the women who helped make it the turning point that it was.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks