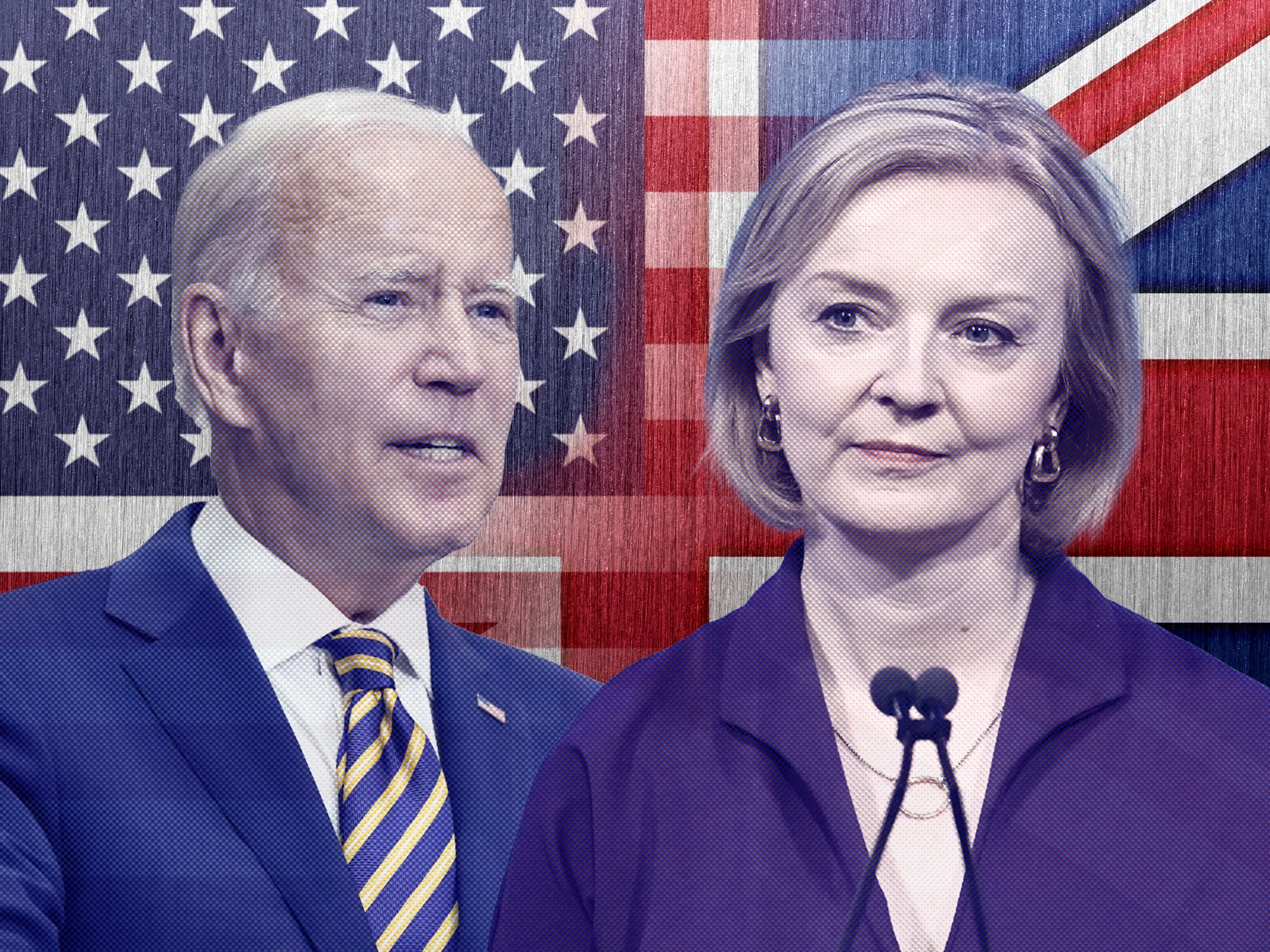

What does Liz Truss mean for Joe Biden and Britain’s ‘special relationship’ with US?

Concern already voiced over new leaders’s plan to scrap critical Northern Ireland free trade provision, writes Andrew Buncombe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Joe Biden and his government may not be utterly thrilled with the idea of Liz Truss as British prime minister, but they will make the relationship work.

Liz Truss may like the idea of putting some space between Britain and the United States. But the importance of Washington to the UK – especially a UK without the supporting guardrails of the EU – means she will not stray so far from the script followed by her predecessors.

That appears to be the boiled-down essence of what is likely to change and what is likely to stay the same, as Truss navigates her way as Britain’s next prime minister, and becomes the focus and driver of the UK’s place in the world.

Experts say she is hampered by the multiple crises she inherits – an economy with soaring inflation, a populace angst-ridden as to how to pay for the winter’s energy bills, a country losing trust in politicians, and a war in Ukraine whose impacts reverberate around the world.

On the plus side, in terms of international engagement and Britain’s relationship with the US, she starts with a clean slate, without the baggage of Boris Johnson and the accusations of dishonesty that led to his departure. People also admire her and Johnson’s stance on countering Vladimir Putin.

“I don’t think there will be a honeymoon period for Liz Truss, not least because there is enormous pressure for things to happen very quickly,” Elisabeth Braw, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington DC, tells The Independent.

“The UK has to address so many things domestically and on the international stage, and within a very short timeframe.”

Last year, when Truss, 47, was appointed Johnson’s foreign secretary and Britain’s de facto top diplomat, she told the Conservative Party conference she wanted to “build a network of liberty across the globe”.

“I reject the voices of decline. I believe that Britain’s best days are ahead of us. We will put the UK at the heart of a network of economic, diplomatic and security partnerships,” she said. “We will help other countries grow through enterprise and trade. And we will make our country more competitive, safer, and freer.”

However, she also claimed while the UK valued its relationship with the US, she considered it “special but not exclusive”.

Speaking at a fringe event to the main conference in Manchester, she was asked about the term “special relationship”.

“I do love the United States, I think it’s a fabulous country and a very close ally of the United Kingdom,” she replied.

“We’ve got other close allies as well. Australia is becoming a close ally of ours, we’ve got important relationships across Europe. We have an important relationship with India.”

She added: “I don’t feel we’re in competition with other countries to be the United States’ best friend. I don’t think these things are a question of some kind of beauty parade of countries and the UK has to be front and centre and we’re worried like some teenage girl at a party if we’re not considered to be good enough.”

For some years after World War II, perhaps mainly when Winston Churchill was alive, American presidents were usually polite enough in public to suggest there was an equity in the relationship between the two nations.

In truth, even when the war still being fought, Britain was very much a junior partner – economically, militarily and strategically.

That disparity has only grown. The US is Britain’s number one trading partner, but the UK is the US’s seventh largest, and in 2019 the US enjoyed a $5.9bn goods trade surplus.

Sometimes individual leaders develop a personal rapport that makes the relationship feel less forced.

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher are said to have got along well, with the prime minister terming him “the second most important man” in her life after her husband, Denis.

Bill Clinton and Tony Blair bonded over so called “third-way triangulation”. And Blair heeded his friend’s advice to maintain a similarly close relationship with his successor, Republican George W Bush.

Blair did that with gusto, determining in the tense, frenzied months after 9/11 that it was in Britain’s interest to join the US’s invasion of Afganistan, and later Iraq, an episode based on lies and false intelligence that cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

It was one of the few times, perhaps, that Britain’s support for the US at the UN, was of genuine value. (Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld made clear he did think the US needed British troops.)

In Washington DC, Biden administration officials reportedly perceive Truss as ideological and driven, but without the bluster of Brexit that Johnson used to deploy to delight the likes of Donald Trump.

And because of her job as foreign secretary, she has already built some relationships with the US, and is better known than Rishi Sunak, her opponent in the leadership race.

The Financial Times noted she has already visited the White House, when she joined a visit led by Johnson, 58, and which was described as “warm”. It also pointed out Truss and Biden are also likely to hold their own meeting on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, which takes place later this month.

Braw says Truss is seen as someone who does her homework and prepares for meetings, something else that may set her apart from Johnson.

If there is one area of genuine concern for the US about Truss, it appears to be her backing of legislation that would change the post-Brexit trade arrangements in Northern Ireland, the so-called Northern Ireland protocol.

While of intense importance to people in Ireland and Northern Ireland, it is also something that concerns many senior members of the Democratic Party in the US.

Earlier this year, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi warned Truss that any change could threaten a trade deal between the UK and US, where many politicians and their supporters – Biden among them – claim Irish heritage.

“As I have stated in my conversations with the prime minister, the foreign secretary and members of the House of Commons, if the United Kingdom chooses to undermine the Good Friday accords, the Congress cannot and will not support a bilateral free trade agreement with the United Kingdom,” she said.

“It is deeply concerning that the United Kingdom now seeks to unilaterally discard the Northern Ireland protocol, which preserves the important progress and stability forged by the accords.”

Braw says the multiple crises may come to Truss’s favour when cementing her personal relationship with Washington DC.

“The US may need the UK less than the UK needs the US, or the US may be less invested in the special relationship than the UK,” she adds.

“But nevertheless, Western partners need one another desperately at the moment, so I think that will help her.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments